Homicide: Life on the Street is one of the long-lost—or, at least, long-difficult-to-watch—TV shows from the era just prior to the golden age of TV. Or, at least, it will be for a little while longer; Peacock has, finally, cleared all the music rights (or as many as possible) for the show to get a proper release on streaming. It’s going to hit the service on August 19.

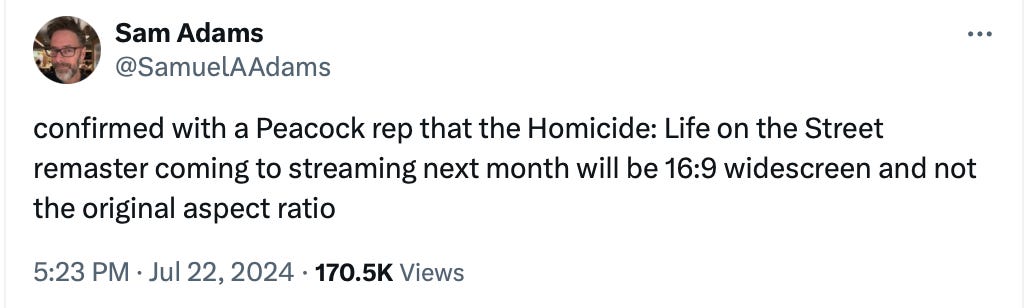

This is a good thing! It’s good when TV shows find a second life on streaming. For a long time, you couldn’t watch Moonlighting basically anywhere. Now it’s streaming on Hulu. People should watch it! (Let show creator Glenn Gordon Caron and me convince you it’s worth your time in this podcast.) When Homicide hits Peacock, you should probably watch it, too. I say “probably” because there’s one minor issue:

This is something of an eternal struggle, as anyone who remembers the days of pan-and-scan will recall. A very truncated history lesson: Once upon a time, televisions were sold in nearly square 4:3, which was the standard size of a movie screen when TVs were developed. (Technically, the Academy ratio is 1.37:1, but 1.33:1 is close enough for government work.) In order to differentiate from TV, movie studios started releasing films in widescreen, experimenting with formats like Cinemascope. Cinemascope, at roughly twice as wide as the Academy ratio, was somewhat unwieldy; eventually, the studios (mostly) settled on 2.39:1 and 1.85:1. These ratio games are still used to differentiate not just theaters from TV but screens from other types of screens. IMAX, for instance, uses 1.43:1 in its boxiest format, though most IMAXes in multiplexes use 1.9:1; naturally, this all gets particularly complicated when Christopher Nolan is involved.

These aspect ratios were fine in movie theaters, where masking could adjust screen sizes, but once movies started being released for home viewing, audiences were confronted with a problem: a film shot in 2.35:1 doesn’t “fit” on a 1.33:1 screen. In order to see the full image as the director intended, the home video presentation had to be “letterboxed” at the top and the bottom with black bars. This led to the sensation of “wasted” screen space.

And audiences hate to feel like they’re being cheated out of screen space. The image is so small! Look at these dumb black bars! Why can’t we use the whole TV? To head these complaints off, studios created something called “pan and scan.” Pan and scan involved blowing up the image so filmmakers could make a 1.85:1 or 2.35:1 film fit the entire 1.33:1 screen, the result being the edges of the action were cut off. If action happened in one part of the frame and then in a different part of the frame, the image would slide (“pan”) over to the other part of the frame.

I don’t mean to be melodramatic, but pan and scan is an abomination before the eyes of the Lord. But don’t take my word for it! Listen to these directors explain why:

The pan and scan problem was largely solved by the advent of high-def, 16:9 TVs. That ratio is very close to 1.85:1, and close enough to 2.35:1 that the letterboxing isn’t as annoying for most people. But this solution created another “problem”: every TV show shot before 2002 or so was shot in 1.33:1, because that was the size of every television.

Which brings me back to Homicide. Being an NBC show released in the 1990s, Homicide was shot in 1.33:1. Nearly no one owns a TV of that shape anymore. Meaning that if you want to watch Homicide on a modern TV, you’ll have to do so with vertical black bars on the sides. Which leads us to the wasted screen “problem.” Other TV shows, confronted by this “problem,” have opted to remaster the show for HD and blow it up to 16:9. A prominent example of this is Seinfeld. Now, credit where it’s due: Seinfeld’s image quality in these remasters is very high! It just comes at the expense of occasionally losing a joke. The lost-joke problem is much worse on animated shows like The Simpsons.

But changing the aspect ratio of a show like Homicide creates other problems. As it happens, Homicide creator David Simon worked on another earlier 4:3 to 16:9 adaptation a decade ago, when The Wire was remastered for widescreen high def. His essay recounting what went into that remaster is well worth reading (and I wish the video clips in it still worked!), but the broad point is this: the effort was painstaking and as much care as possible was given to avoid changing the mood of the show. As with anything else in life, the final product results in a tradeoff:

There are scenes that clearly improve in HD and in the widescreen format. But there are things that are not improved. … Still, being equally honest here, there can be no denying that an ever-greater portion of the television audience has HD widescreen televisions staring at them from across the living room, and that they feel notably oppressed if all of their entertainments do not advantage themselves of the new hardware. It vexes them in the same way that many with color television sets were long ago bothered by the anachronism of black-and-white films, even carefully conceived black-and-white films. For them, The Wire seems frustrating or inaccessible – even more so than we intended it. And, hey, we are always in it to tell people a story, first and foremost. If a new format brings a few more thirsty critters to the water’s edge, then so be it.

I have no idea if the transfer done by Peacock is just as exacting or carefully overseen; I hope it is. And I would argue that nothing would be lost by offering both options to viewers. Disney+ offers early seasons of The Simpsons in both 4:3 and 16:9; it would be nice if Peacock did something similar with Homicide. But if this is what it takes to get Homicide: Life on the Street in front of more viewers … well, I guess it’s a necessary evil.

This week I reviewed Deadpool & Wolverine, a movie that I more or less enjoyed but also kind of hated myself for enjoying. So, you know. Mixed bag? But it’s pretty entertaining if you’re into these movies. Spoilers in this, so don’t click unless you’re fine with that.

‘Deadpool & Wolverine’ Review

[Note: I have no idea how to write this review without discussing plot points or cameos, so if you’re worried about that sort of thing, please read this after you see the movie. My overall judgment …

Southwest Airline’s Boneheaded Decision

Note: This is not really Hollywood-related and it’s not really politics-related but it is kinda-sorta culturally related. I guess. Also, Sam Stein asked me to write about it and writers have to listen to editors, that’s the law.

News broke yesterday that Southwest Airlines is making some changes. They’re going to offer some seats with more legroom. They’re going to start offering overnight “red eye” flights to a handful of locations. And, most crucially, they’re going to get rid of the free-for-all boarding style that is the hallmark of the service and go to a more traditional assigned-seating system.

And guys, let me tell you: I hate this almost as much as I hate pan and scan.

Now, to be clear, I have not always been a Southwest guy. I, like so many of you, found the non-assigned seating to be a little off-putting at first. “I have to line up? And then just pick a seat? What the hell?”

But when I moved to Dallas, I quickly became a Southwest guy. First, for reasons of convenience: the airport in Dallas proper is Love Field, and Love Field almost exclusively flies Southwest planes. It’s the closest thing Southwest has to a “hub,” I guess. And from Love Field I can get nearly anywhere in the country I need to go, usually direct, in about 2.5 hours. It rules.

Secondly, though, I came to appreciate Southwest’s idiosyncratic boarding process. It’s deceptively simple: when you check in for your flight, you’re given a boarding number, 1-30, divided into three boarding groups, A, B, and C. You line up in numerical order, As first, then Bs, then Cs. Then you … enter the plane! And take a seat! It’s the fastest system used by the U.S. airlines; you can get a plane loaded in just 20 minutes this way. I always add the Early Bird option, which essentially guarantees boarding in the A group, meaning that I’ll a.) always have overhead space (even though you can check bags for free on Southwest, I prefer to have mine handy when I deplane) and b.) be able to get an aisle or a window seat, depending on how I feel.

I know there are some folks who don’t enjoy the uncertainty, who dislike having to decide who to sit next to. So many choices! So awkward. But it … isn’t? Really? Like, at all? You just sit where you want to sit. Most flights are full anyway, so you’re not actually inconveniencing anyone by sitting next to them. And the 1-30, A-C boarding process is so much more transparent than every other garbage airline’s process, all of which have something like 17 different boarding groups, all corresponding to a different class of passenger, each one with their own privileges. Again, as someone who is typically more worried about overhead space than which specific seat I’m in, this is always incredibly annoying to me; I don’t want to have to guess if I’m boarding after the Premier Plus Blue Status Cherished Member Service Set in group four but before the General Premium Syrinx Priest Class in group six. Just numbers and letters, that’s all I need.

And look: lots of people like having assigned seats. That’s fine! There are a million other airlines that do it just like that! Go fly on one of them! Southwest does things differently. It’s nice to have the option available! STOP MESSING WITH WHAT WORKS FOR ME SPECIFICALLY, SOUTHWEST.

Assigned Viewing: Lousy Carter (Hulu)

I talked to Bob Byington and David Krumholtz, respectively the director and star of Lousy Carter, earlier this year when the film hit VOD. I hope you rented the movie after listening. But if you didn’t rent the movie—shame on you for missing this 80-minute comedy about a professor who learns he has six months to live and must decide what to do with himself—you can now watch it for free on Hulu. It’s an offbeat sort of picture, but one I quite enjoyed; in addition to great performances by Krumholtz, Olivia Thirlby (with whom Krumholtz costarred in Oppenheimer), Martin Starr, and Stephen Root, there’s also a breakout turn by Luxy Banner. She plays a college student that Lousy (Krumholtz) is half-heartedly trying to seduce with a delightfully disaffected vibe. Shades of early Aubrey Plaza. With any luck, more folks get a chance to see what she does in this movie now that it’s streaming for free.

A formative moment of my youth was when I went to purchase a widescreen version of The Matrix on VHS, and the clerk at Suncoast Video said, "You know that's going to have the black bars on it, right?"

Sonny is an underutilized talent at The Bulwark. Love the movie stuff, but culture writing needs more play!