Every week I highlight three newsletters that are worth your time.

If you find value in this project, do two things for me: (1) Hit the like button, and (2) Share this with someone.

Most of what we do in Bulwark+ is only for our members, but this email will always be open to everyone. To get it each week, sign up for free here. (Just choose the free option at the bottom.)

Also: Almost all of the newsletters I link to have free versions. You only pay if you want to upgrade. So don’t hesitate to click through and sign up.

1. What I’m Hearing

I’ve linked to Matthew Belloni before and I feel slightly guilty doing it again so soon, but this week his newsletter hit on an important macro-economic trend. Belloni looks at how the economics of streaming have transformed the income landscape of Hollywood:

Back when I was a young lawyer, I’d often get assigned to Hollywood accounting cases. Some big talent—David Duchovny on The X-Files, Peter Jackson with The Lord of the Rings, the showrunners of Home Improvement, to name a few—would make something that earned a ton of money, their backend checks wouldn’t be as big as they’d hoped (or wouldn’t arrive at all), so they’d request an audit and discover the studio was stiffing them on profit participation—their cut of the revenue based on the negotiated definition in their contracts.

These were interesting cases because they taught me all the ways vertically integrated entertainment companies make money on a film or TV series—the “waterfall,” in studio parlance. But at their core the disputes were all the same: Studios set the table via complicated profit definitions (some are dozens of pages long), then gorged on self-serving calculations and phantom “fees,” and often the talent was left with relative scraps. Or at least that was the view of the clients, all of whom came to my firm because they were really pissed off.

It’s because of this background that I’ve become concerned about the recent dramatic changes in how talent is compensated in Hollywood. Most insiders are familiar with the general shift: Amazon and Netflix started “overpaying” people in exchange for a “buyout” of their backend. Why? Global digital distribution and a membership model largely suck the water out of the waterfall, and calculating an accurate backend requires basic transparency in ratings and revenue, which streamers abhor. Of course, eliminating traditional backends also meant killing the so-called “home runs,” where stars and creators could make hundreds of millions of dollars off a major hit. Instead, the streamers would capture all of that value for themselves. . . .

But now the streaming model has effectively eaten the entire television business, allowing the traditional studios to “update” their own form deals and realign who makes what, sometimes to the detriment of top talent. The base floor might be slightly higher, but the ceiling is much lower, and, like in the rest of this country, the healthy middle class is disappearing. . . .

Disney has largely shifted from backend profit definitions to something called a “Series Bonus Exhibit” . . . It’s complicated, but the main difference is the shift to a largely fixed compensation arrangement, rather than a sliding profit participation based on the consumption—or “hit” status—of a show.

This better reflects the new streaming economy—“we aren’t fighting over formulas; now we’re just fighting over money,” one lawyer explains—but it also has major implications for talent. For a top creator, who might have negotiated for 10 or 15 participation points on a series in the old days, this new S.B.E. calculation would be worth a fraction of those points. On a mid-range hit, that translates to someone who once made $40 million now making $10 million, according to top agents. On a big hit, a $150 million payday becomes something like $25 million. And it’s worse at the very top: If you create Modern Family, you might make $30 million now on an S.B.E. formula instead of $200 million or more on a traditional backend.

You should subscribe to Belloni’s newsletter. It’s great.

But what I want to talk about here is how often we see this transformation when the internet disrupts an industry.

Let’s take the taxi.

Taxis are a business for a century. Used to be that you could be a taxi driver and have a middle-class life in America. Maybe a lower-middle-class life, but still.

Then Uber comes along and transforms the economics of taking a taxi. Suddenly consumers get a marginal increase in value while taxi drivers get decimated as an industry. (Driving an Uber is not a gateway to the middle-class.) Where does all of the money from that extra value accrue? Up the stack to a bunch of tech bros.

Once upon a time, if you lived in Nashville, or New York, or LA, you could make a living as a song writer. You didn’t get rich like the performers, but you could buy a house, put your kids through college.

Streaming music has utterly destroyed that career.

The ur-example here is Kevin Kadish, who co-wrote “All About That Bass,” the mega-hit which was streamed 178 million times. His total compensation for those streams?

It is not the case that the internet destroyed the value of song-writing. It simply re-directed the compensation away from the middle-class value creators and to a small cadre of wealthy tech companies.

In a great many instances, the internet does not “transform an industry” so much as “transfer the wealth” from a diffuse group of workers in the existing industry itself to a smaller group of owners in the tech sector.

One cheer for capitalism?

2. Noah Smith

He’s everyone’s favorite neoliberal and last week he did a deep dive on the Democrats’ growing danger with Hispanic voters. Lots of #RealTalk.

On election night 2020 and immediately after, as it became apparent that Hispanic voters were shifting to Trump, there were a lot of instantaneous explanations that turned out to be wrong. It’s just Cubans! It’s just Florida! Wrong, and wrong. Some people focused on Latino men shifting to Trump, but guess what, Latinas shifted even more!

Many tried to minimize the size of the swing, but a new Pew report — which counts only voters whose identity can be validated in public records — reveals just how big it was. Trump garnered 38% of Hispanic votes, compared to only 27% for Mitt Romney in 2012. . . .

I think one big, powerful explanation has been sorely neglected: Economics.

The boom of 2014-2019 — and it was a boom, even though we kind of ignored it — was good for everyone, but in percentage terms it was especially good for Hispanics . . .

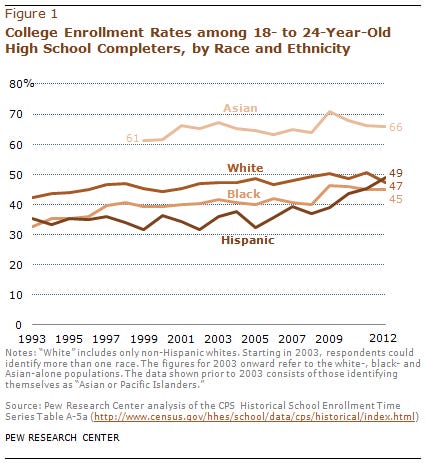

How are Hispanics moving up in America? The same way immigrant groups generally move up — by building human networks, moving to opportunity, and getting an education. Here are two startling graphs about how Hispanic Americans have been climbing up the educational ladder:

In other words, despite starting from a very humble base, Hispanics are treading the same upward path that American immigrant groups always tread. The history of the Irish, Italians, Poles, and so on is repeating itself. . . .

And anyone who has been paying even the slightest bit of attention to the progress of Hispanic Americans over the decades knows that this is exactly the reason they came here. When Mexican immigrants waved American flags at pro-immigration rallies in the 2000s, they weren’t just courting public opinion — they really believed in this country, and in the American Dream they were promised. The dream of working hard, bettering yourself, and moving up. They were immigrants, damn it. And their children and their grandchildren remembered that dream as well — and now they’re achieving it. America has kept the promise it made.

So why would this make Hispanics shift toward the GOP? Maybe it’s because Trump presided over the most recent boom, in which Hispanic incomes did so well. Maybe it’s because when you start moving up the economic ladder, you get the urge to protect your gains with low taxes.

But it might also be because many liberals have been disparaging the American Dream. In 2015, a faculty training guide at the University of California warned professors that calling America a “land of opportunity” constituted a microaggression. Liberal rhetoric has turned increasingly against the notion of the American Dream, both because of the people who are still excluded from it — undocumented immigrants, many Black and Native American people, many people caught up in the justice system, etc. — and because of rising inequality. To call America a “land of opportunity” seems, to many liberals, a cruel taunt directed at those who still don’t enjoy full opportunity. . . .

Now, you might respond that this derogatory attitude toward the American Dream is confined to media outlets, shouty activists, and overzealous university administrators. But in this age of ubiquitous social media exposure, politicians don’t have the luxury of merely standing above the cultural fray — they have to actually address the things that it seems like “their side” is doing all over the country. And conservatives, for their part, are racing to take advantage of the situation, claiming that Biden’s programs are aimed at ending the American Dream. It’s all B.S., of course — Biden’s programs would enhance and strengthen the American Dream (I’ll write more on this in subsequent posts). But if woke pundits and clucking university admins are running all over the country denouncing the idea that the American Dream even exists, then there’s no one to push back on conservative alarmism.

If they want to make sure that the Hispanic trend toward the GOP remains a blip, Democrats need to start talking about the American Dream again. And more than that, they need to focus their policies on upward mobility for working-class and middle-class strivers.

3. Embedded

It’s a newsletter by Kate Lindsay and and Nick Catucci about a bunch of things, but mostly internet culture. And every Friday they interview someone who is very online. This week it was Ben Smith:

Would you say that you have an Instagram aesthetic? How would you describe it?

Inattentive Dad

What type of stuff do you watch on YouTube?

Handyman stuff, part of the vast body of incredibly useful and uninteresting YouTube.

Are there any influencers who you would be sad to see stop posting?

I'm going to wedge Gustavo Arellano into this category, because I couldn't find another place to put him and his mix of brilliance, irascibility, and genuine open-mindedness is so vanishingly rare on Twitter.

Do you ever tweet? Why?

Constantly, since 2009. It's the greatest global public forum in human history and an incredible joke machine. Also, obviously, has the capacity to make you crazy and distort your work, and I don't think I've found a great balance.

Which platform do you put the most effort into posting on?

Are you regularly in any groups on Reddit, Slack, Discord, or Facebook? What are they about?

I use reddit for a mix of niche things (eg Geocaching) and all sorts of problem solving—my son recently pointed out to me that if you add the term "reddit" to any sort of "how do I" Google search, you get better results. Facebook for neighborhood groups, and was incredibly grateful when a neighbor found my dog and posted there—the single best use of the platform. One of my kids only communicates with me through Discord, so that's on my home screen, and I dip into Sidechannel there occasionally. I left all the New York Times Slacks but one to avoid being seen as a narc, and do enjoy that one which my colleagues generously set up to quarantine me.

Do you consider yourself part of any specific online communities?

A few—a certain generation of political reporters, I think, who feel, often wrongly, we've seen it all before. Everyone who ever worked at BuzzFeed.

Are you a gamer?

Not really. Occasionally play Fortnite.

Do you have a go-to emoji? What does it mean to you?

Prayer hands. Thank you! People are always telling me things, and I'm grateful.

Forkin’ Ben Smith. I love that guy. Read the whole thing and subscribe.

If you find this valuable, please hit the like button and share it with a friend. And if you want to get the Newsletter of Newsletters every week, sign up now. It’s free.