THERE’S A SHOT ABOUT HALFWAY through The Iron Claw that kinda-sorta tells the whole story of the Von Erich wrestling clan.

Von Erich patriarch Fritz (Holt McCallany) is in the ring standing in front of his boys, Kevin (Zac Efron), David (Harris Dickinson), and Mike (Stanley Simons). As we slowly push in, Fritz announces to the world that Kevin, the eldest, won’t be the next to get a title shot as everyone thought: He’s not as good on the mic as his brother, David, and he got hurt in his big opportunity against Harley Race (Kevin Anton), betraying weakness. David will get the chance instead. And one day Mike—a skinny little nothing who wants to be a musician, not a musclebound mauler—will join his brothers in the family business.

It’s an immaculate and subtle piece of acting, this tableau. Fritz never wavers, never shows a sign of doubt. However, the boys are all a little confused. This isn’t what they want: not for themselves, not for each other. But they don’t get much of a say. There’s a legacy to be upheld, and Fritz is the architect of it. In the burgeoning pro-wrestling world of the late 1970s and early 1980s, where regional circuits competed with each other and attempted to avoid being swept up by the consolidation-hungry Vince McMahon, you needed a man with a plan, and Fritz saw himself as that man. He saw himself as THE man, actually, and always resented the fact that he never got a chance to hoist the biggest of the championship belts during his own heyday. His children would accomplish what he never did.

That the lives of the Von Erich children would frequently and legendarily end in tragedy—dying both by their own hands and from illnesses, victims of a supposed curse inherited by the name their father had taken when he stepped into the squared circle1—is of seemingly limited concern to Fritz or their mother, Doris (Maura Tierney). All part of God’s plan. Or at least a god. Saturn, devouring his sons one by one.

This all sounds mildly depressing, and The Iron Claw is, to an extent, mildly depressing. But it is also ultimately hopeful, even inspirational. A male weepie, for sure; this is pure, testosterone-fueled melodrama. There’s a scene near the end that I won’t describe here except to say that it has no place in a realistic picture of this sort and is vaguely absurd and yet still made my eyes fill with saline. But it’s entertaining and comforting in its own way. I rarely feel nakedly pandered to at the movies, but this is a movie that needle-drops Rush’s “Tom Sawyer” on top of a montage of 1980s professional wrestling about a family of hard-working folks who see their dreams shatter when the dastardly Jimmy Carter pulls the United States out of the Summer Olympics, costing Kerry Von Erich (Jeremy Allen White)—and, by extension, Fritz—his shot at gold.

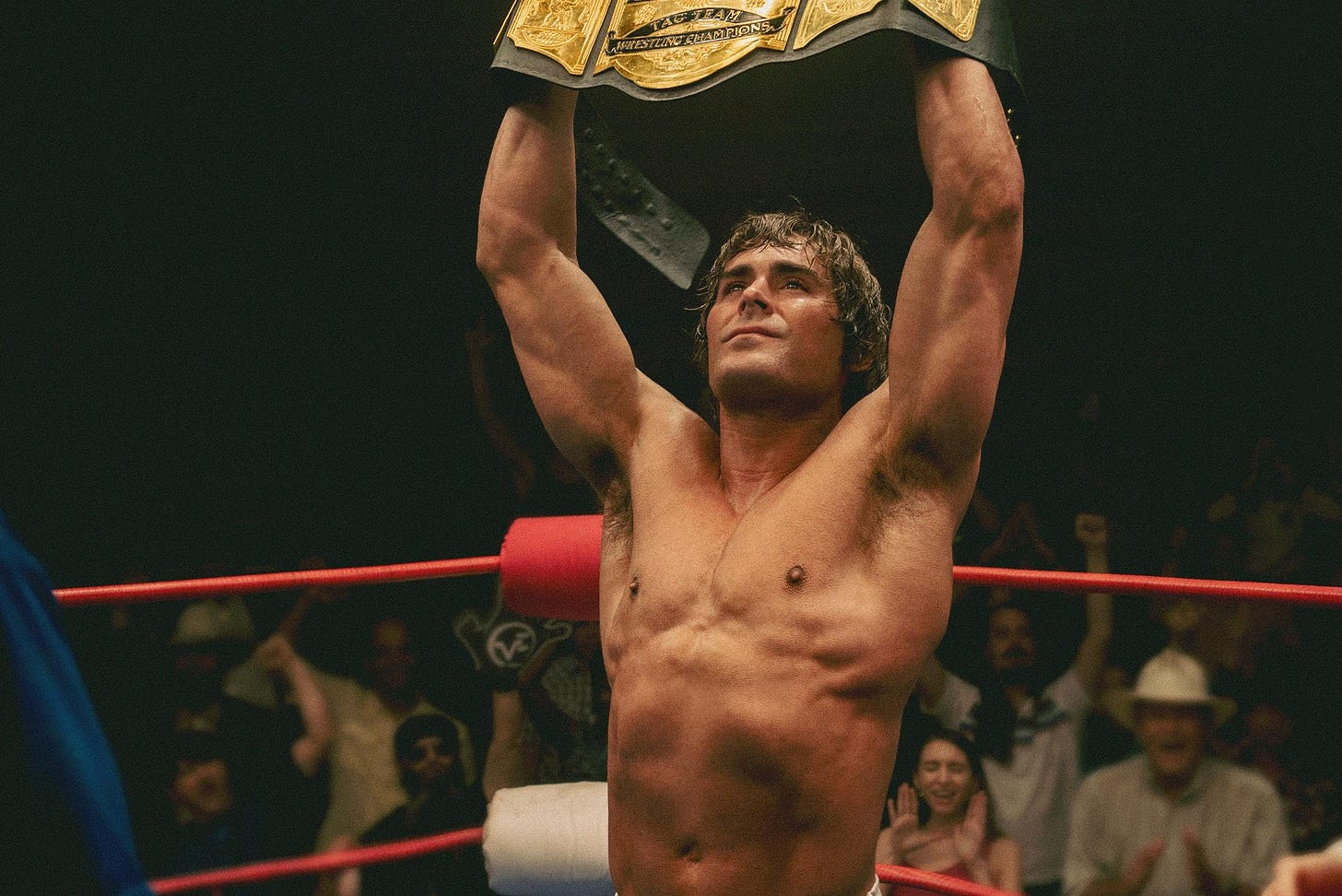

The performances are all top-flight. Holt McCallany is, rightfully, getting some Oscar buzz for his turn as Fritz, but it’s Zac Efron who steals the show. He has packed on muscle without losing any of his litheness; watch the sequence in which he’s effortlessly line dancing while the rest of his brothers practically have their tongues outside pursed lips in concentration. But the muscles don’t overpower his melancholy. It’s a heartbreaking performance from one of our most underrated actors.

FERRARI IS ABOUT FAMILY LEGACIES of a different sort.

As the film opens, Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver) is on the way back to his home from an assignation. He pops his head in, gets some bad news, gets shot at by his wife, Laura (Penélope Cruz), and, unharmed, heads off to the graveyard, where he goes to see his son, Dino. And here the film slows, takes its time. Enzo is near, and then leaking, tears, thinking about his boy, how much he misses him, how he sees his face whenever he closes his eyes. Yes, he sees his brother sometimes too, but it’s his son that haunts him.

Unlike Fritz Von Erich, Enzo Ferrari is a man who is secure in his professional legacy. He was a successful, if not tremendously so, racecar driver; he founded and then turned Ferrari into one of the most legendary brands the world has ever known. Yes, he is struggling a bit in 1957, when this film takes place, to keep everything together—his company teeters on insolvency and competitors are threatening his cars’ speed records and his wife is on the verge of leaving him—but he doesn’t need a son to accomplish what he never could.

But sons and fathers are their own special, complicated thing even absent professional obligations, and they grow even more complicated when questions of legitimacy are thrown into the mix. Enzo, as it happens, has a son named Piero (Giuseppe Festinese) with Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley). What does Enzo owe this boy? What does he owe his wife, who has lost her only child and who has been made to feel shame for failing to deliver an heir to the Ferrari name? What does he owe the company he has built, the town whose economy he drives, the hundreds of men he employs? How does one balance the moral weight of all these questions?

It is interesting that for all his alpha males—from the lawmen of Heat and Miami Vice to the hitman of Collateral to the world’s greatest boxer (Ali) and TV news producer (The Insider)—director Michael Mann has never before tackled head-on the idea of fatherhood and what we owe the generations to come. In most of his films, his professionals are married to their jobs; they are frequently alone, though rarely lonely, and most of them echo Enzo’s belief that “when a thing works better, it is usually more beautiful to the eye,” whether that thing is a heist or a journalistic breakthrough or a hit. Manhunter, Heat, and The Last of the Mohicans all tangentially touch on the topic of fatherhood, but typically as a way to illuminate some other thematic point. Ferrari is the first of Mann’s films to really ask whether a man can be complete without a family—or if a son can be complete without a father, properly recognized, fully in his life.

That Laura and Enzo cannot reconcile Piero’s existence in a world without Dino only deepens that complication.

Like The Iron Claw, Ferrari is very much an actors’ showcase. Driver and Cruz are just magnetic on the screen, Cruz in particular. It’s funny: Mann has clearly tried to make her look a bit more dowdy onscreen than she is in real life—her dress is a little frumpy; she walks with a mannered waddle—but Penélope Cruz is Penélope Cruz and no dowdification can alter that fact. There’s a smolder that can’t be smothered.

You’ll note I haven’t even really discussed the car race that comprises most of the last 40 minutes of the film; all I’ll say is that Mann understands both the beauty and the terror of a car that can take hairpin turns at high speed. These sequences are scary in a way that car races rarely are, and if I have one complaint about the picture it’s that I would’ve liked a bit more time in the driver’s seat with Enzo’s racers.

The filmmakers actually chose to leave one of the real-life Von Erich brothers entirely out of the movie on the grounds that including his tragic death would have been one too many.