The Judge with the King Complex

Should trial judges have the power to issue nationwide injunctions? A lawsuit over abortion drugs is the latest major case to raise the question.

This month, less than a year after the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade, a ruling is expected in another abortion-related federal case that could have wide-reaching effects. The case is less interesting for its substance, though, than for how it demonstrates the troublingly outsized power of low-level federal courts to effectively write policy for the entire country via a practice called “nationwide injunctions.”

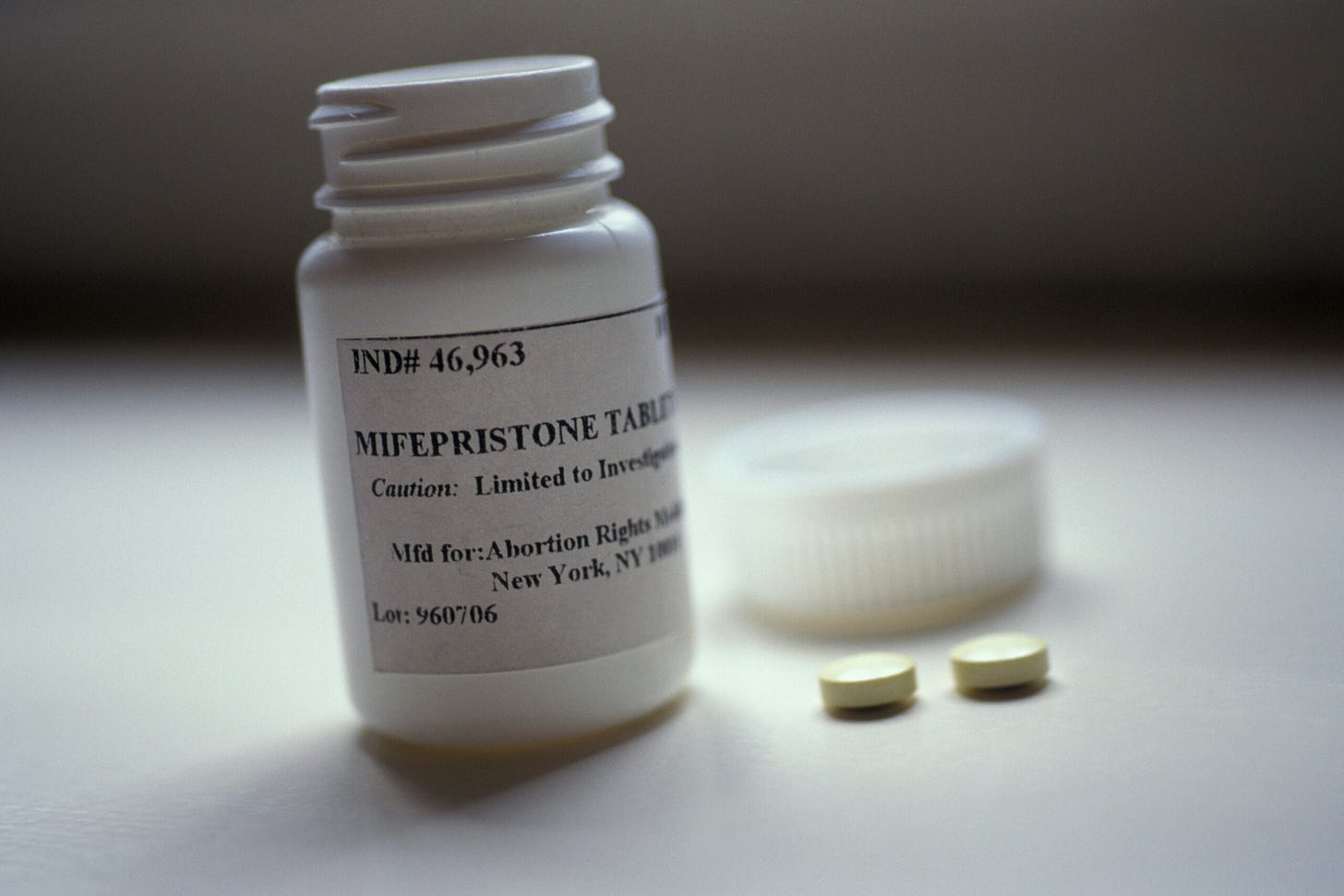

Filed last year by Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative legal group, and a number of individual doctors, the case (Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA) seeks to overturn the Food and Drug Administration’s 2000 approval of the drug mifepristone (also known as “RU-486” and “Mifeprex”) for use in ending pregnancies through ten weeks gestation. As of 2020, about half of all abortions in the United States rely on pills (usually mifepristone in combination with misoprostol), which patients and providers happen to prefer anyway. In December 2021, because of the pandemic, the FDA for the first time since its initial 2000 approval of mifepristone allowed women to obtain the drug at a pharmacy or through the mail. Scores of studies show that since, travel time for abortion care—which is now banned in 13 states and restricted in several others—went from 30 to 100 minutes on average.

The lawsuit seeks a preliminary injunction that would immediately suspend all approvals of abortion-related drugs, alleging more specifically that the FDA’s 2000 action, and subsequent related actions the agency took, exceeded its authority under the Administrative Procedure Act; the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) and Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA); and a regulation that authorizes the agency to approve on an “accelerated” basis medications “that have been studied for their safety and effectiveness in treating serious or life-threatening illnesses and that provide meaningful therapeutic benefit to patients over existing treatments.”

The government argues that none of the plaintiffs has an actual injury sufficient to confer standing to bring the lawsuit because none of them actually prescribes the drug. The physicians claim that other doctors will prescribe mifepristone to patients who will experience adverse effects and then complain to the plaintiffs who will then divert time and resources from other patients, which could potentially cause them grief and guilt, as well as create potential exposure to civil liability and insurance costs. The government argues these attenuated chains of alleged harm are way too speculative to justify constitutional standing to sue, which is designed to keep courts out of the business of policymaking. The FDA also argues that the claims are legally stale.

On the merits, the plaintiffs allege that FDA relied on bad science, which included clinical trials and data on adverse side effects. Under the FDAAA, Congress authorized the FDA to require a “risk evaluation and mitigation strategy” before approving a drug in order to ensure that the benefits outweigh the risks. The government argues (rightly) that the court must apply a deferential standard here—it’s not empowered to substitute its judgment for the FDA, whom Congress deputized to make these decisions. So long as the FDA’s decision that the risks of the drug were outweighed by the benefits was “reasonable and reasonably explained,” it should be upheld. At a minimum, the extraordinary relief of a preliminary injunction—which is generally reserved for immediate emergencies—should be denied.

Nonetheless, two procedural wallops make it virtually certain that opponents of abortion will score with this lawsuit: first, the assignment of the case to U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, a Trump appointee who sits in the Amarillo Division of the Northern District of Texas; and second, Kacsmaryk’s willingness to employ a constitutionally controversial tactic known as a “nationwide injunction” to mandate policy for the country.

Kacsmaryk was confirmed 52 to 46 by a Republican-controlled Senate in 2019. His conservative views on human sexuality are made clear in his writings published for a general audience, like a 2015 article from a few days before the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision on same-sex marriage that quoted the Catechism of the Catholic Church in saying “homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered” and “contrary to the natural law.” In another 2015 article, Kacsmaryk distinguished the “Civil Rights Movement” from the “Sexual Revolution” by reasoning that “the former was rooted in the soil of the uniquely American Judeo-Christian tradition, spearheaded by Christian leaders” while “the latter was rooted in the soil of elitist postmodern philosophy, spearheaded by secular libertines, and was essentially ‘radical’ in its demands” in that

it sought public affirmation of the lie that the human person is an autonomous blob of Silly Putty unconstrained by nature or biology, and that marriage, sexuality, gender identity, and even the unborn child must yield to the erotic desires of liberated adults.

In his four years on the bench, numerous conservative causes have magically made their way to Amarillo, undoubtedly due to its receptive judicial audience. In February, the Justice Department filed a motion to transfer out of Kacsmaryk’s courtroom a case challenging federal policy allowing 401(k) managers to consider climate change and other societal factors when investing clients’ money under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, arguing that “Plaintiffs’ decision to forum shop by filing in the Northern District—and, in particular, in the single-judge Amarillo Division, which has no connection whatsoever to this dispute—undermines public confidence in the administration of justice.”

DOJ is right to be concerned about Kacsmaryk and his power to affect the entire country.

In August 2021 and again in December 2022, Kacsmaryk ordered the Biden administration to reinstate and abide by the Trump administration’s immigration policy requiring asylum seekers to remain in Mexico pending a hearing—despite a sitting president’s constitutional prerogative to make policy at the border. (The Supreme Court overturned his first ruling in June.) In October, he ruled unlawful a guidance document issued by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to counteract Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s order directing the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate sex change procedures performed on minors. And in December of 2022, he sided with “a Christian who is ‘raising each of [his] daughters in accordance with Christian teaching on matters of sexuality, which requires unmarried children to practice abstinence and refrain from sexual intercourse until marriage’” in striking down HHS regulations under Title X of the Public Health Service Act that allow for the funding of family planning services for minors without requiring parental consent.

This is, to be clear, an extraordinarily unusual run for a single lower-court judge.

And now, there is little doubt that Kacsmaryk will side with the Christian right when it comes to the FDA’s decades-old approval of mifepristone for early-term pregnancy terminations. Although he could be reversed on appeal, in the interim such a ruling would likely keep thousands of women from accessing mifepristone and could effectively change policy through osmosis as doctors and pharmacies adapt to a new normal.

Of course, every judicial ruling has a winner and a loser—that’s part of the deal. What makes the FDA case so troubling, in addition to this particular unelected judge’s track record of making national policy from Amarillo, is the thorny question of nationwide injunctions. The term is not defined anywhere—not in the Constitution, not in a federal statute or procedural rule, and not in a Supreme Court decision. Informally, nationwide injunctions have two primary characteristics: they are against the government, preventing it from implementing a law or policy; and they apply to everyone in the country, including parties that aren’t even before the court—and thus may not have constitutional standing to sue in the first place if they tried to bring the case themselves.

In 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a memorandum to DOJ attorneys warning against nationwide injunctions and arguing that the “trend must stop.” The constitutional arguments are manifold, including that judges are confined under Article III of the Constitution to resolving discrete disputes between parties. Congress and (to a lesser degree) the president make policy because they are electorally accountable. The practice of issuing nationwide—versus discrete, party-specific—injunctions was unheard of before 1964 and has increased since. Only 12 were issued during George W. Bush’s presidency. By contrast, 55 were imposed during the Trump administration, including against his ban on certain foreign nationals entering the United States.

President Biden has been slapped with nationwide injunctions against his COVID-19 vaccine mandate for specified Medicare- and Medicaid-certified providers, his student loan forgiveness program, his replacement of Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” policy for migrants (thanks to Kacsmaryk), and his pause on new oil and gas leases on public lands. Not only does the practice tread into presidential turf, it sidesteps the benefits of allowing multiple judges across the country to address an issue thoroughly before it percolates up to the Supreme Court for final, uniform resolution.

The justices on the Supreme Court appear to be mixed on the question, with Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch urging restraints on nationwide injunctions and Justice Sonia Sotomayor arguing that such relief may be necessary in a particular case. As with much of what’s wrong with American law and politics today, the solution lies largely at the feet of an often cowardly and ineffective Congress, which has a range of options at its disposal to rein in activist judges (including, for that matter, the far-right Supreme Court itself). They include confining courts’ jurisdiction—and thus their ability—to entertain such actions; establishing firm legislative criteria for issuing them; or channeling such cases to a three-judge court. If nothing happens legislatively, one of these days the unelected Supreme Court will make policy on this topic in Congress’s stead. And time and again, the nation has seen how problematic empowering life-tenured politicians can be.

Whatever one’s opinion is on the delicate and agonizing balancing act that abortion policy requires and what role the government has in that balance, it’s hard to argue that a single, ideological, and unelected judge in a small town in Texas should be resolving the issue for the hundreds of millions of the rest of us. It’s time for Congress to step up and do the bare minimum on this issue: fix judicial procedures to make the system more reasoned, fair, and, well, judicious.