We call Christmas the “season of giving” but that’s only half true. Look a little deeper and what we see is that Christmas is the season of giving-receiving. When my children were young and eagerly anticipating Christmas morning and not knowing what they’d say, I asked, “Why do you think we give gifts at Christmas?” The response was immediate and inspired, “Because God gave us his son and now we give gifts to each other to help us remember.” Giving, receiving, and giving again is the true pattern of Christmas. If we’re attentive, we can see it is also the pattern of life woven through the fabric of human experience.

As a pastor once told me, humanity’s primary reality is visible in our bellybuttons: We come from somewhere; we are born out of relationship into relationship. Martin Buber, relaying an old Jewish saying, tells us, “in the mother’s body man knows the universe, in birth he forgets it.” The mutuality of human existence begins in conception and continues to death. We are made to depend upon others and to be a source of life for others. As I hold my new granddaughter on my lap this winter, a child we’ve been told faces significant physical and mental challenges, I’m acutely aware that even this helpless babe radiates life and renews hope in me. Mysteriously, in nurturing her, we ourselves are nurtured. We help with the diapers and feeding and soothing. She does the important work of loving. It is not nearly as one-sided as it might appear.

And this is not just metaphysics but a lesson that science continues to teach us. The study of human neurological and social development shows us that to develop well, human beings require other human beings. No human is an island; no one’s slate is truly blank. We need food and shelter but we also need touch, a characteristic we share with other primates, and emotional engagement. Paradoxically, human individuality requires what psychologists call stable, healthy attachment to others. Studies of hospitalism—depriving infants and young children of the love and care of adults—shows what happens when we are left alone: We withdraw within ourselves, we waste away. We die.

I am convinced it is a shortage of human warmth and connection that lies at the heart of almost all the social ills that afflict us, from abortion to addiction to homelessness. As a society, we are paying a high price for a hemorrhage of loving mutuality from the system of human exchange.

Several years ago, I had the privilege of helping to translate Signs of Love: Christian Liturgy in the Everyday Life of the Family, a book by Don Renzo Bonetti, an Italian priest who leads a marriage and family ministry called Mistero Grande, the Great Mystery. The book and the organization are two of many efforts by theologians, priests, philosophers, and the laity around the world who are grappling with the implications of St. Pope John Paul II’s Theology of the Body and what its insights might mean for a future John Paul believed would pass “through the family.”

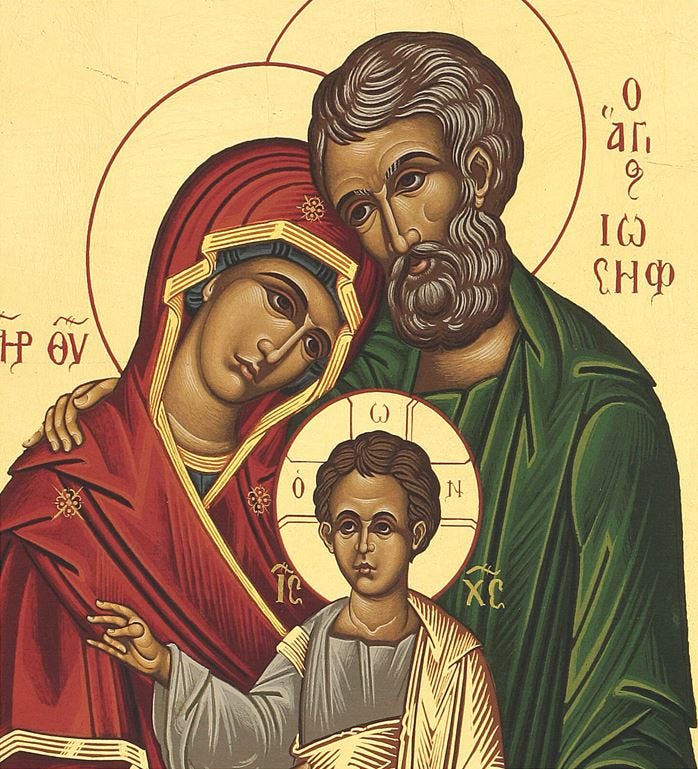

Signs of Love is grounded in Ephesians 5, St. Paul’s great hymn of the church, in which he invokes the loving self-donation between spouses as a three-dimensional expression of divine love, an icon not of wood and paint, but in flesh and blood. If we want to understand the operation of the Trinity, and how three persons can become one person, Paul and Bonetti say, look to the marital union. In marriage, they say, we see spouses, joined by the Holy Spirit, in a domestic, “one-flesh” tri-unity that forms a miniature and imperfect replication of the life of the Trinity itself.

I think this iconography of the family helps explain the enduring power of St. Luke’s Christmas story.

Installed at the very center of the tale is the miraculously pregnant Virgin (“May it be done unto me according to your word”) accompanied by an older, not-quite-comprehending husband, St. Joseph Most Obedient. Present but unseen, the Holy Spirit, guides, leads, and prepares the way. Magicians and shepherds and angels accent the birth in which the Second Person of the Trinity takes on the mantle of humanity and enters time. The reason the story is so indelible is that the writer has framed it unflinchingly in the most common and most extraordinary of all human experiences, the birth of a child into a family. In the birth of Jesus, we see the inflection point of all history anchored in the love and mutual donation of family life, and behind that, in the life of God.

In other words, God prioritizes relationship to such a degree that he embedded it within himself and imprinted it upon our nature, which might be why the Bible tells us we are made in his image. Mutuality finds its way into—indeed, serves as the basis of—human activity of all kinds. From family, to community, to work, to politics, when mutuality is distorted disrupted things don’t go well. Day in and day out, in matters large and small, public and private, we are given a choice: We must live the law of the gift or perish without it.