The Legal Case for the Senate to Convict Trump

Open and shut.

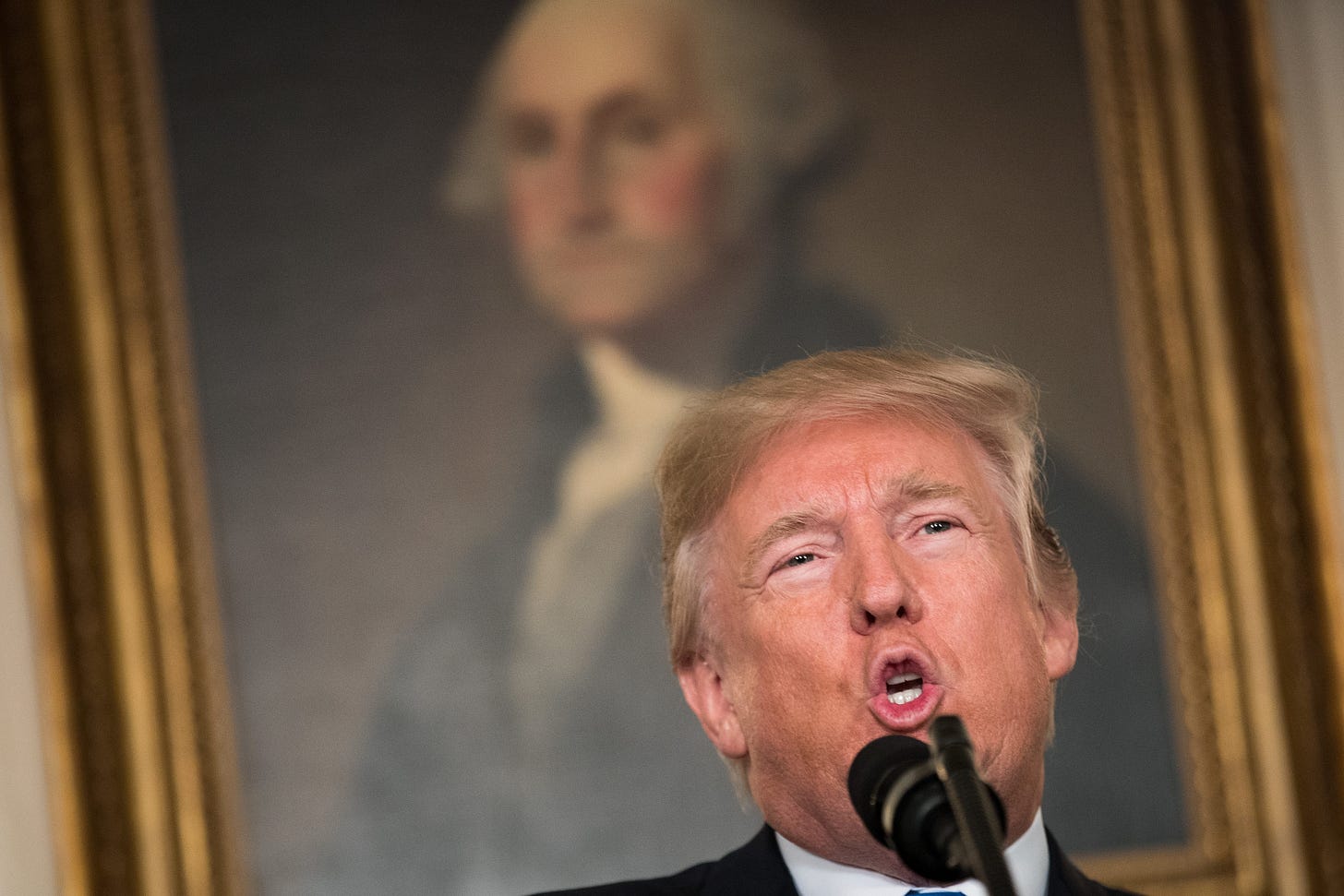

On January 13, 2021, the House of Representatives impeached President Donald Trump for the second time.

As of the date of this writing, the Speaker of House has not yet sent the Articles of Impeachment to the Senate for trial, so we don’t know when, or even if, a trial will take place.

Assuming there is a trial in the Senate, however, the case for conviction is clear and compelling.

The specific ground for Trump’s second impeachment, “incitement of insurrection,” immediately takes off the table two of the core defenses Trump asserted last year when he was impeached for the first time:

The conduct alleged against him might have been inappropriate, but it wasn’t a crime; and

Crime or no crime, the alleged misconduct didn’t rise to the level of an impeachable offense.

Defense No. 2—that the alleged misconduct doesn’t rise to the level of an impeachable offense—is plainly not available in Impeachment II. The very thought that inciting an insurrection against the United States doesn’t rise to the level of an impeachable offense is laughable. If inciting an insurrection against the United States isn’t an impeachable offense, nothing is.

Defense No. 1—that a specific statutory crime must be alleged and proved to impeach and remove a president—isn’t really a defense at all. Rather, it’s a fringe theory rejected by the vast majority of constitutional scholars.

But even if proof of a statutory crime were required, it would not help Trump escape conviction this time around because Impeachment II does charge Trump with a crime.

Incitement of insurrection is a crime, full stop: 18 U.S.C §2383 states that any person who “incites” or “assists” an insurrection, or “gives aid or comfort thereto,” shall be fined or imprisoned for not more than ten years, “and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.”

Since the sufficiency of the charge on its face is not at issue, the Senate trial will focus primarily on deciding whether Trump is guilty as charged. Process and political calculations will also come into play, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

For now, let’s take a look at the strength of the legal case against Trump.

Because incitement always involves some form of speech, courts and legal analysts have struggled to define a bright line between speech that is protected under the First Amendment and speech that isn’t. Simply put, not all speech is “free” or constitutionally protected. Think, for instance, of laws prohibiting fraud, defamation, and criminal conspiracies.

Generally speaking, speech that is merely offensive, shocks the conscience, or even repulses audiences is protected by the First Amendment. Even speech that advocates the use of force or the commission of unlawful acts is generally protected.

However, there are exceptions. Speech designed to incite imminent lawless action is not protected.

Drawing the line isn’t always easy, but there are guideposts. Over a hundred years ago, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes put it this way in Schenck v. United States:

The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.

More recently, the Supreme Court in Brandenburg v. Ohio summarized the development of the law this way (the emphasis is mine):

[Previous court] decisions have fashioned the principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.

The precise articulation of the standard aside, this much is clear: context is crucial in determining the line between protected advocacy and prohibited incitement. Courts will look at not only what was said, but when it was said, where it was said, to whom it was said, and, crucially, whether it was foreseeable and likely that the speech would incite imminent unlawful conduct.

So, let’s look at Trump’s January 6 speech, the one on which his impeachment was almost exclusively based, in both words and context.

At around noon on January 6, Trump faced an angry, agitated mob of somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 of his supporters who had gathered at the National Mall, less than a 10-minute walk from the United States Capitol.

The mob was angry because Trump had systematically made them so in a relentless two-month campaign of lies. Trump claimed, over and over, that the 2020 presidential election had been “rigged,” that he had actually won the election “by a lot” (despite the fact that the certified election results showed that Joe Biden had won convincingly), and that the supposed election fraud was “the biggest SCAM in our nation’s history.”

Trump’s pre-January 6 grooming of his supporters wasn’t just a campaign of lies, it was a call to action. Trump summoned his supporters to Washington D.C. specifically on January 6, not merely to express their dissatisfaction, but to do something concrete: “Stop the Steal.”

Trump’s call to action culminated when he exhorted supporters at a January 4 rally in Georgia to “take back” the election:

If the liberal Democrats take the Senate and the White House—and they’re not taking this White House—we’re going to fight like hell, I’ll tell you right now . . . We’re going to take it back.

This statement on January 4 is a good point of reference because it shows how speech can not be considered incitement: Trump is calling for violence, but in an unspecified manner at an indefinite time. This is the kind of context that makes such speech protected.

The context of January 6 was very different.

On the morning of January 6, the mob Trump had summoned assembled just a short walk from the Capitol, where a joint session of Congress was underway to tabulate the election results. This group was angry and prepared for violence: Many in attendance were dressed in combat gear, with helmets and body armor. Some were openly brandishing weapons, others were carrying concealed firearms (in contravention of local law). Others were waving Confederate flags or bedecked in anti-government and anti-Semitic messages.

It was clearly known that many in the crowd were prepared to take violent action. They had openly bragged that they were going to do so, and they had already started even before the rally began. At least ten Trump supporters had been arrested the night before, mostly on weapons charges, after clashing with police. The FBI had issued an explicit warning that extremists were preparing to commit violence and “war.”

It was in this context that Trump stood to address the mob late in the morning of January 6. It is this context in which his words must be understood.

Trump began his speech by telling the press to turn its cameras to show the crowd “because these people are not going to take it any longer.”

Trump flogged his “we’re not going to take it any longer” theme incessantly throughout his speech, peppering his remarks with variations of “we’re not going to take it” and “our country has had enough,” and “we’re not going to let that happen” at least a dozen times.

And he told the crowd exactly what he wanted them to do about it.

First, he aimed them at a target: “We’re going to walk down to the Capitol;” “we’re going to walk down, and I’ll be there with you;” “I know that everyone here will soon be marching over to the Capitol building;” “We’re going to the Capitol.”

Then he told them exactly what he wanted them to do when they got there: “We will stop the steal.”

The meaning of this phrase was unmistakable. At that point, after the votes of the electors had been certified, the only way to “stop the steal” and overturn the election was to stop the joint session of Congress from performing the constitutional duty it was attempting to perform at that very moment.

And so the insurrection was launched. It succeeded in part and failed in part. It succeeded in delaying Congress from performing its constitutional duty—and likely in intimidating a number of members of Congress into supporting their cause. It failed in that it did not ultimately prevent Congress from doing its job.

Some of Trump’s defenders insist that his speech should be judged entirely by the presence of a single word that Trump uttered 18 minutes into his hour-and-a-quarter exhortation to action: “peacefully.” But the same context that protects Trump’s remarks from January 4 makes the single use of “peacefully” on January 6 look more like consciousness of guilt than an attempt to prevent violence.

Context truly is everything. And it cuts both ways.

At the end of the day, there is no legal defense for Trump’s conduct. He incited the insurrection. The Republicans in the Senate know it, so during any eventual trial they will focus on process and political arguments.

The process arguments will go pretty much like this: The impeachment process was rushed, without witnesses, hearings, or an opportunity for Trump to defend himself. And there’s no constitutional basis for a Senate trial because Trump is already out of office.

The “rush to judgment” argument is, for the most part, without merit. Yes, the impeachment took place at warp speed, but it was based entirely on actions that took place in full public view, almost entirely on television. Since there are no material facts in dispute, hearings would have been pointless and unnecessary, nothing more than a showcase for political rhetoric.

The “he’s already gone” argument is more complicated. There is some precedent for holding a Senate trial after the impeached official has already left office, but it’s scant and not particularly relevant. Whether the Senate can hold an impeachment trial after the official is already out of office is a legal question that can and almost certainly will be decided by the Supreme Court, probably before any trial takes place. If the Supreme Court says no, then there will never be a Senate trial.

If there is a trial, Trump’s defenders will rely primarily on political arguments. They will argue that convicting Trump will further divide and inflame the country at a time when we should be seeking unity, not further division.

Put aside the grotesque level of hypocrisy in this plea. From a practical perspective, it is simply not true: There is absolutely no reason to believe that foregoing a Senate trial will lower the rhetoric or promote national unity in any way that matters. We know this because with or without a Senate trial, large numbers of elected Republicans have continued—and will continue—to claim that Joe Biden stole the election, that Donald Trump was the rightful winner, and that our federal government is illegitimate.

Until the majority of elected Republicans stop spreading this lie and admit that they have been lying about the election, then there will be no “unity.” Forgoing an impeachment trial isn’t going to pacify people who believe that Joe Biden’s presidency is the product of a putsch.

We’re in for a hard rain, Senate trial or not. There is nothing to be gained by trying to assuage the feelings of white supremacists, conspiracy theorists, and other MAGA crazies.

It’s time to hold bad actors accountable, not to appease them. It is time to let the truth have its day.