The controversy over Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law, which severely curbs the ability of public schools to teach about sexual orientation or gender identity, has brought the spotlight on the extent to which the culture wars over public schools now have to do with transgender identities and the recent dramatic shifts in liberal and progressive views on the subject. Unfortunately, this controversy replicates an all-too-familiar pattern: Conservatives respond to a real problem—in this case, progressive overreach in proselytizing simplistic and strongly disputed beliefs on a contentious issue to often-young schoolchildren—in ham-fisted ways, resulting in accusations of both bigotry and speech suppression; liberals circle the wagons and deny that there is any real problem, attributing the conservative moves solely to intolerance and reactionary backlash against social progress; over-the-top accusations proliferate on both sides; and the chances of productive conversation dwindle from slim to none.

Make no mistake: Florida’s Parental Rights in Education bill, which was signed by Republican culture warrior and likely presidential aspirant Gov. Ron DeSantis on March 28 and takes effect on July 1, is bad law. True, it does not prohibit anyone from saying the word “gay” in or out of public schools, and the groups paying for those “Say Gay” billboards in Florida could definitely find a better use for their money. On the face of it, the text of the bill may even seem reasonable: “Classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” But it’s not clear whether, for instance, the prohibition on sexual orientation “instruction” in K-3 would cover such things as a parent volunteer during a class activity mentioning a same-sex spouse, or the use of any book or cartoon with a gay character.

The “age-appropriate[ness]” in later grades could also be a thorny issue—especially since, like some other recent social-issues legislation, the bill empowers ordinary citizens to serve as enforcers by suing. Given how stupid the culture wars have gotten, that’s worrisome.

It is also true that the anecdote DeSantis used as a justification for the bill—a supposed incident in which schoolteachers encouraged a 13-year-old student to explore a transgender identity without the parents’ knowledge or consent—turns out to have been substantially misreported: It seems that in reality, school staff was fully cooperative with the parents. (One of the bill’s provisions requires such cooperation, except in cases of a credible risk of abuse, when the child is making potentially life-altering decisions.)

But that doesn’t mean concerns about gender-identity extremism in educational settings are all made up.

Right now, for instance, these concerns are being aired in my own “blue” state of New Jersey as health and sex education standards passed into law statewide in 2020 and now being implemented by local school boards have drawn objections not only from Republicans and conservatives but from some Democrats and moderates. For the moment, Gov. Phil Murphy, a Democrat, has announced that the guidelines are being reviewed by the Department of Education and stressed that parents will always have the right to opt their children out of the lessons.

What’s so controversial? While some of the objections have focused on elementary-school materials that include overly explicit descriptions of sexual anatomy, proposed lesson plans dealing with gender identity issues have been a particular lightning rod. Thus, a cartoon video on “Puberty and Transgender Youth” suggested by one local school board as potential viewing material for fifth graders casually discusses the use of puberty blockers and shows a character experiencing anxiety because of by bodily changes (and apparently using a chest binder to hide developing breasts) and getting an injection of puberty blockers.

Meanwhile, a sample lesson plan recommended by that same school board for first graders instructs teachers to ask children how they know what gender they are, then explain the concept of gender identity as “that feeling of knowing your gender,” and elaborates:

You might feel like you are a boy, you might feel like you are a girl. You might feel like you’re a boy even if you have body parts that some people might tell you are “girl” parts. You might feel like you’re a girl even if you have body parts that some people might tell you are “boy” parts. And you might not feel like you’re a boy or a girl, but you’re a little bit of both. No matter how you feel, you’re perfectly normal!

A second-grade lesson from the same curriculum more specifically identifies “male genitals” and “female genitals,” but also offers this disclaimer: “There are some body parts that mostly just girls have and some parts that mostly just boys have. Being a boy or a girl doesn’t have to mean you have those parts, but for most people this is how their bodies are.” (While the Washington Post has pointed out that these lessons plans are not mandatory but are simply offered as potential resources, they are still among the approved material for the curriculum.)

Let’s stipulate that these are difficult subjects to teach, that these are contentious subjects for communities to debate, and that education can play a part in improving the mental health outcomes for transgender individuals. But even a liberal who believes that tolerance requires teaching first and second graders about transgender identities is likely to find these texts rather baffling. The lesson plans do not say that some people, including kids, feel their inner sense of their gender does not match their biological sex or their genitals; rather, the claim is that for some unspecified reason some boys happen to have parts that “some people” associate with girls, and vice versa. This text reflects what has become activist orthodoxy in recent years: that transgender women or girls do not transition from male to female but were always women or girls who happened to be misgendered (and, conversely, trans men and boys were always men/boys). Hence the widespread adoption of the phrase “assigned male/female at birth,” among other terminological shifts.

A recent video made by Massachusetts-area transgender teacher Ray Skyer during an “identity share” Zoom session with kindergartners rather starkly highlights this viewpoint. Skyer, who teaches at a public charter school, explains that when he was a child, his parents and other people wrongly thought he was a girl:

So when babies are born, the doctor looks at them and they make a guess about whether the baby is a boy or girl, based on what they look like. And most of the time that guess is 100 percent correct—there are no issues whatsoever. But sometimes the doctor is wrong; the doctor makes an incorrect guess. When a doctor makes a correct guess, that’s when a person is called cisgender. When a doctor’s guess is wrong that’s when they are transgender.

Are parents reactionary if they think the claim that sex at birth is established by the doctor “making a guess” is not only terrible science, but a highly confusing message for children whose sense of themselves and the world is still developing and for whom the boundaries between fantasy and reality may be still unstable? (Like many other children, I went through an “I’m a boy” phase when I was 7, not long after other phases in which I was a dog, the goddess Artemis, a prehistoric cave child, and a variety of fairly-tale characters of different sexes and species.) Or if they think that the schools should not be in the business of endorsing puberty-blocking drugs whose long-term effects are still poorly understood?

Other parents who are not GOP activists from Florida but suburban liberals from places like Stamford, Connecticut have pushed back against reading materials like The Pants Project, a book about a transgender boy assigned in grades 3 to 5. The objections have been not only to overly sexualized material—the main character, Liv, muses at one point, “Last week, Chelsea loudly told Jade that she’d seen a bulge in my underwear (I wish!)”—but to “gender stereotypes”: the book, one mother complained, seemed to imply that all girls are girly and that wearing pants, as Liv hankers to do, is a boy thing.

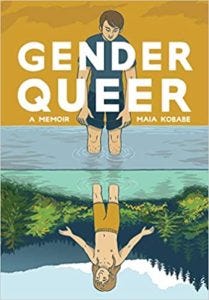

Some of the pitfalls of school materials promoted in the name of transgender inclusion are illustrated by a controversial graphic (that is, comics-style) book for older teens titled Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe. The book, an account of the author’s journey of gender exploration originally published in 2019 and set to be reissued next month, is atop the American Library Association’s “10 most challenged books” list for school libraries this year.

The outcry over Gender Queer has focused mainly on several pages that contain sexually explicit material: references to masturbation, fantasies about gay male sex, and (most of all) an episode in which Kobabe experiments with wearing a strap-on penis and being fellated. I will say, at the risk of being considered a puritan, that I have doubts about whether such material belongs in a high school library. But after reading Gender Queer on Kindle, I came away thinking that the sexually explicit material was not the book’s most troubling aspect.

Kobabe is a talented artist and writer, and the book is a vivid, often poignant account of growing up socially awkward and sexually confused. Young Maia, a child of hippie parents who had very little contact with other children until first grade and didn’t learn to read until age 11, constantly felt ignorant and socially inadequate; the feelings of inadequacy were exacerbated by puberty, which brought with it some excruciating body image issues. Periods become a source of intense anguish and shame; nearing 30 when the book was published, Kobabe mentions having menstruation-related nightmares to this day. Breasts are so loathsome that Maia fantasizes about getting breast cancer just to get them amputated. The thought of bearing children feels repellent; pregnancy is perceived as “carrying a parasite.” A gynecological exam turns out to be so horrifically painful that it’s envisioned as comparable to being run through with a sword.

Despite occasional fantasies about having a penis and being a glamorous gay man, Maia’s real wish, ultimately, is not to be a man but to be androgynous and genderless. Eventually, after becoming involved in LGBT activism, Kobabe comes to identify as nonbinary and asexual, adopting the pronouns “e/em/eir” and developing such intense revulsion to being seen as a woman that being referred to as “she” causes physical pain. Ironically, the nonstandard pronouns become a new source of distress, making gender salient in numerous encounters in which Kobabe has to correct people who use “she” and “her”; that include slipups by Kobabe’s own parents. (I have to confess that my sympathy for the author’s struggles vanished on the page where Kobabe’s long-suffering mom wails, “Why are you doing this to us?” and Kobabe urges her to think of it as a mental agility exercise.) An official letter that uses Kobabe’s preferred pronouns occasions a wave of joy, but nonbinary identity does not resolve Kobabe’s issues around having a female body: wearing a chest binder becomes de rigueur, and when Kobabe finally has another gynecological exam it is accompanied by so much anxiety that the speculum feels “like a knife being shoved into my vagina.”

At one point, the book suggests that Kobabe’s androgynous identity is a result of atypical brain wiring and hormone receptors. But the entire memoir screams unresolved psychological issues, and there is no indication that the author ever tried counseling.

At the end of Gender Queer, Kobabe muses about helping other nonbinary youth discover themselves. It is, no doubt, a sincere and well-meaning wish. And yet I cannot help thinking that this book can be a deeply toxic influence for a teenage girl struggling, as many teenage girls do, with body image issues, shame about menstruation, and anxiety about not being conventionally feminine. The right answer to these struggles, the book seems to suggest, is a rejection of womanhood, and not just in the sense of rejecting traditional feminine norms: what’s being repudiated is female identity and the female body.

A full analysis of today’s gender identity debates is certainly beyond the scope of this article. However, it is worth noting that extremism in the transgender rights movement is being increasingly challenged across the political spectrum. Jonathan Rauch has recently written a thoughtful essay on the subject for the American Purpose, arguing that the movement needs to reject ultra-radicalism the way the gay rights movement did to win its civil rights victories. The Los Angeles Times last week reported on clinical psychologist Erica Anderson, who is herself transgender and has worked with numerous transgender patients; Anderson has broken ranks with the trans advocacy community by arguing that too many teenagers are being rushed into transitioning and that being transgender or “genderqueer” has, in some cases, become a trendy thing among progressive young people. Science journalist Jesse Singal, who is no one’s idea of a conservative or a right-winger, has been writing for several years about the bad science and bad ideas of radical trans advocacy.

There has been extreme and genuinely bigoted rhetoric about transgender people, both from the right and from radical feminists—but there has also been a disingenuous and deeply counterproductive campaign to equate all dissent from transgender-movement orthodoxy with bigotry and hate. It is entirely possible to believe that transgender identities are valid and worthy of social respect and that gender transition is in many cases the best solution to gender dysphoria, and yet also to believe that transgender advocacy in its current form raises many difficult issues that are far from settled—including hard questions related to gender transition for minors.

Unfortunately, our toxic political scene is the worst possible arena to address these complicated issues. Right now, the right is screaming “groomer” at anyone who believes sexuality and gender identity should be even mentioned in a school setting, while the left is screaming “murderer of trans kids” at anyone who thinks we should be careful about letting a 16-year-old get a mastectomy to fit a male or nonbinary gender identity. The moderate voices are essential—but too often they are getting drowned out. Today, responsible liberals and centrists are well aware of the bigotry and extremism of the anti-trans right; but they should pay more attention to the intolerance and extremism of the militant trans-advocacy left.