'The Night House' Review

Plus: Disney is starting to panic about access to China.

The Night House review

I feel like this disclaimer is unnecessary, but I’m going to be discussing some plot points from The Night Houseand if you want to go in with as little knowledge as possible, please read this later.

Depression is a monster against which it is hard to defend.

This is one of the reasons why The Babadook is so terrifying. Sure, it is nominally about an apparition invading the house of a single mom; in reality, it is a grand metaphor for postpartum depression and the horror of being unable to fully love the very child you gave birth to. And it is at least part of the reason why The Empty Man works as well as it does: If you strip away the Cthulhu-style mythos that bogs down the back half of that picture, it is about suicide contagion and the feeling of emptiness that comes with a lack of meaning and purpose in life.

Into this burgeoning canon of movie malaise steps The Night House. As the film opens, Beth (Rebecca Hall) is trying to come to terms with the fact that her husband, Owen (Evan Jonigkeit, who also starred in The Empty Man), has killed himself. They seemed happy. He didn’t have any demons. Why did he shoot himself in the middle of the lake outside their home? What did he mean in his suicide note when he wrote “You were right. There is nothing. Nothing is after you. You’re safe now.” Why did her husband build a shack that resembles their home, but backwards, in the woods? Why does he have photos of women who look like Beth on his phone?

And why does Beth keep experiencing terrifying dreams that feel all too real and involve a ghostly presence invading her home?

The Night House is moody and tense and mysterious, using the geometry of a home and the shapes and shadows within rooms to create the suggestion of something terrifying hiding just around an edge, just out of sight. Beth’s unreliability—when is she dreaming? When is she awake? How much of her trouble has to do with her penchant for guzzling brandy throughout the evening?—gives added weight to the moments when we gain an insight into her state of mind. Like when she wakes with a start and her laptop browser is open to a page of handguns. That’s never a good sign when a person who admits to “thinking dark thoughts” is involved.

The suicide note is the key, and as we learn early, on “nothing” has a different resonance for Beth. She’s been plagued by dark thoughts since her younger days as a result of a near-death experience. Her heart stoppage did not suggest a light at the end of the tunnel or fields of grain in an Elysium beyond. No, no. This is the other kind of near-death experience. The one that promises darkness and emptiness. The one that posits there is nothing beyond.

Is that the “nothing” that is after her? Did she infect Evan with it? And if so, how does one defeat what is nothing more than despair?

Literalizing this particular concept is always tricky; one of the reasons The Babadook gets away with it is because the real-life consequences of the depression-monster in the film are minimal. I don’t want to spoil anything here, so all I’ll say is that in The Night House the consequences are … not minimal. And these consequences make that metaphor for depression a bit slipperier than the filmmakers might have intended.

Still:

The Night House is scary, well-acted, stylish, and gestures toward profundity. Go see it in a theater so you can share the scares.

If you want more from me on low-budget horror movies, check out my essay on why Don’t Breathe 2 doesn’t really work as a sequel to Don’t Breathe. If low-budget horror isn’t your jam, listen to my podcast with Zak Penn—the writer of Free Guy, PCU, Last Action Hero, Behind Enemy Lines, and X-Men: The Last Stand—about his latest number one box office hit, why PCU remains unavailable, and his theory on how to make villains work on screen.

And If you need to talk a scaredy-cat into seeing The Night House, please share this newsletter!

Marvel’s China Woes Continue

I harp on the China issue a fair amount in this newsletter because it’s one of the most important things to understand about the economics of Hollywood. The rise of China as a box-office superpower coincided neatly with the decline of home video as a major driver of revenue for movie studios: At their peak in 2005, DVDs were generating $16.3 billion in sales, or nearly double the domestic box office total for all films released that year; by 2018 that figure was down to $2 billion (with a similar number for Blu-ray); by 2020 digital sales had outpaced physical media sales altogether.

Yes, Hollywood studios have been picking up money from licensing films to streamers and, increasingly, starting their own streaming channels. However, it’s a classic case of trading physical dollars for digital pennies, and the DVD boom of the 2000s—fueled by competition between big box stores and catalog titles finding second life as DVDs—will not be topped by streaming revenue anytime soon, if it ever is. In short: There are more avenues of revenue than ever before, but the studios are generating nowhere near the total revenue they were 16 years ago from home video.

All of which is to say that the billions of dollars in Chinese box office generated by franchises like the MCU and the Fast and Furious films came along at the perfect time to fill holes in Hollywood’s spreadsheets. But these billions came with a catch: As Chris Fenton notes in his book Feeding the Dragon, to gain access to the Chinese market you have to play ball with the Chinese government. (For more on that, listen here.) That means tailoring your movies to meet the standards of not only the Chinese government but also the Chinese people. And it means engaging in self-censorship even when making something that’s not intended for the Chinese market, as free speech watchdog PEN America has reported American studios regularly do.

The fact that Disney and Marvel, a prime innovator in the space of placating Chinese censors and appealing to Chinese audiences, are having trouble getting Black Widow, Shang Chi, or The Eternals in Chinese theaters is a promising and perilous sign for Hollywood studios.

The peril is obvious and you can understand why Marvel chief Kevin Feige is trying so desperately to smooth things over with China: There’s a lot of money at stake and it’s hard to make a $200 million movie profitable without access to the Chinese market.

The promise is this: Those of us who love film at its best and hope it can be more than a nine-figure special-effects extravaganza may get more of what we want as studios realize that the explosion-oriented filmmaking designed to cater to Chinese teenagers is no longer profitable. More modestly budgeted fare could flourish.

Then again, the collapse of the Chinese market might just mean the death knell of theaters altogether. After all, movies like Stillwater and The Green Knight (which have grossed $12.5 million and $14.7 million, respectively) aren’t keeping multiplex lights on. As long as Black Widow is grossing more domestically on its opening day than those films do in their entire runs combined, it’s still a blockbuster’s world.

Even if that world’s on borrowed time.

Assigned viewing: The Dark Knight (HBO Max)

The Dark Knight remains one of the best movies ever made about the war on terror; from issues of surveillance to enhanced interrogation to extraordinary rendition to the nature of nihilistic terror, the movie was less about Batman and more about the age in which it was released.

One portion of the film that doesn’t get a lot of consideration, however, is the argument against leaving such matters up to the general public. Think back to the moment when the Joker reveals that he has planted bombs on two ferries, one filled with criminals and one filled with civilians. The villain gives them a choice: Either one of the boats blows up the other boat or the Joker will blow up both boats.

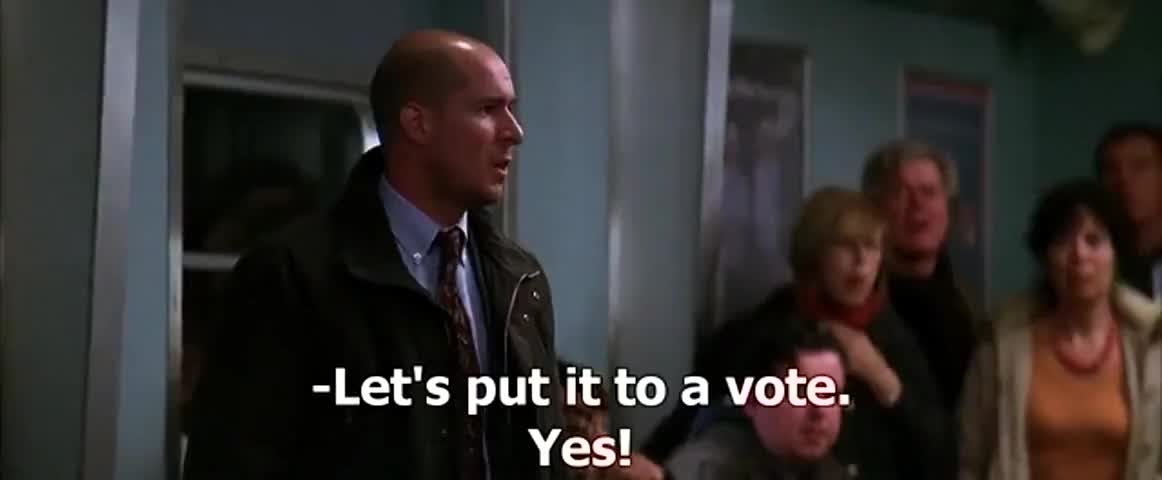

The response on the civilians’ boat is outrage that they might die. They can’t believe it. They demand a vote to condemn the other boat’s passengers to death. “Who are you do decide?” a businessman asks a police officer guarding the trigger. “We ought to talk it over at least.” “Those men had their chance,” another ferry passenger replies. So they put it to a vote, and the vote is 340 votes for blowing up the ferry with the criminals, 196 against.

I bring this up in part because it’s worth considering that this is, roughly, how the public split on the Iraq surge in 2007 (not quite two to one against), and even those who are keyed into the political undertones of The Dark Knight rarely comment on this critique of democratizing national security. But mostly, I mention it because the language used by the upright citizens trying to talk themselves into killing a boatload of strangers—“Those men had their chance”—feels not entirely dissimilar to the language used by those who would justify abandoning the Afghans to the Taliban. (For instance: “We gave them every chance to determine their own future. What we could not provide them was the will to fight for that future.”)

Anyway. Something to keep in mind if you sit down for a rewatch of Nolan’s masterpiece anytime soon.