1. The Natural Gas Scare

If you were looking for unknown-unknowns to worry about over the next six months, here’s one:

Have you seen the price of natural gas recently? It’s up. Way up. There are news reports out about it today blaming the spike on the big storm that has hit Texas.

Which is partially true. The storm has taken a lot of gas off-line.

But this spike predates the storm.

Last week the price for physical delivery in Oklahoma hit $600/mBTUs. The previous record was $40. As of Wednesday, it had been trading at $2.50.

I know this stuff is boring, but I want you to just look at some of the numbers to get a general sense of my alarm before we move on to the high level take-away:

Natural gas hit a record $600 per million British thermal units in Oklahoma. Temperatures fell so far below forecasts in parts of the central and western US that physical gas prices soared from California to the Rockies, with one hub in Cheyenne, Wyoming, reaching as high as $350 per mmBtu . . .

Heating and power plant fuel traded for as much as $195 per mmBtu in Southern California. If day-ahead electricity prices are any indication and the weather forecasts are even partly accurate, the run-up in energy prices isn’t over. . . .

Wholesale power for delivery Sunday was trading at anywhere from $3,000 to $7,000 a megawatt-hour in some places, triple the records set in some places Saturday and a staggering 2,672% increase from Friday at Texas’s West hub.

Traders on Saturday said they’ve never seen electricity trade on Texas’s grid for thousands of dollars for such a sustained amount of time. They drew comparisons between this week’s price surges to the records set on the Midwest grid in 1998, and to the California energy crisis that sent power prices skyrocketing and blacked out hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses two decades ago.

Temperatures this low and heating demand this high could test Texas’s electricity price caps on Sunday. . . .

Gas in Chicago hit $220 per mmBtu, traders said.

Physical gas was going for as much as $300 per mmBtu at a Texas hub. . . .

Gas processing plants across Texas are shutting as liquids freeze inside pipes, disrupting output just as demand jumps. And oil production in the Permian Basin, the biggest U.S. shale play, is moderating as wells slow down or halt completely.

So we can all agree: Not good.

Now let’s move on.

Why do we care?

Well, we care because this natural gas shortage is behind the rolling blackouts in Texas. That’s bad.

But we also care because there are macroeconomic considerations. Over the last several years, energy prices have gone down. Consistently. This is what natural gas prices look like since 2008:

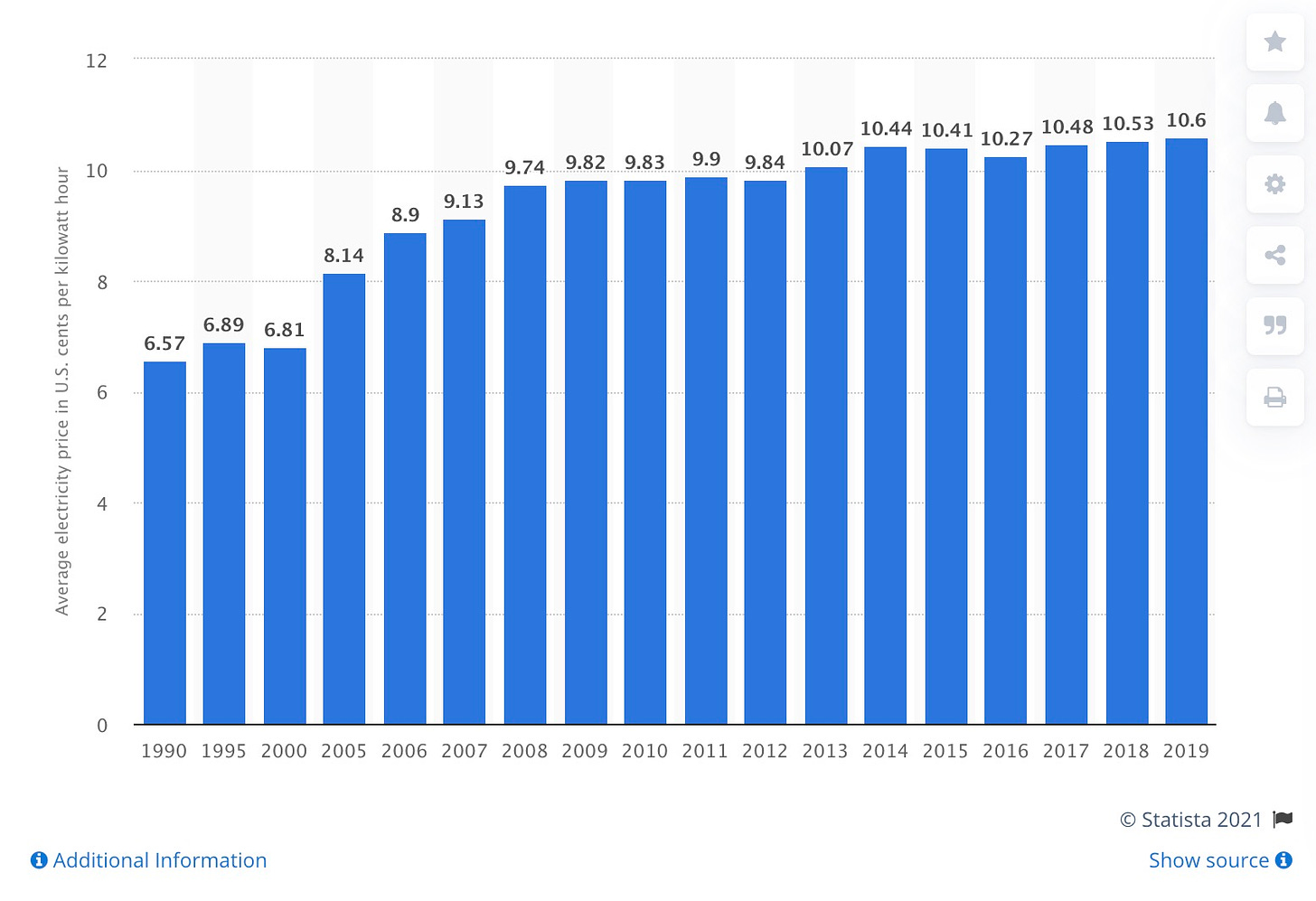

Since 2014, retail electricity prices have been essentially unchanged:

Over the last half dozen years, the economy’s been getting a hidden stimulus that’s probably on the order of magnitude of a trillion dollars.

If energy prices suddenly start increasing, that stimulus disappears.

Or worse.

2. Supercycles?

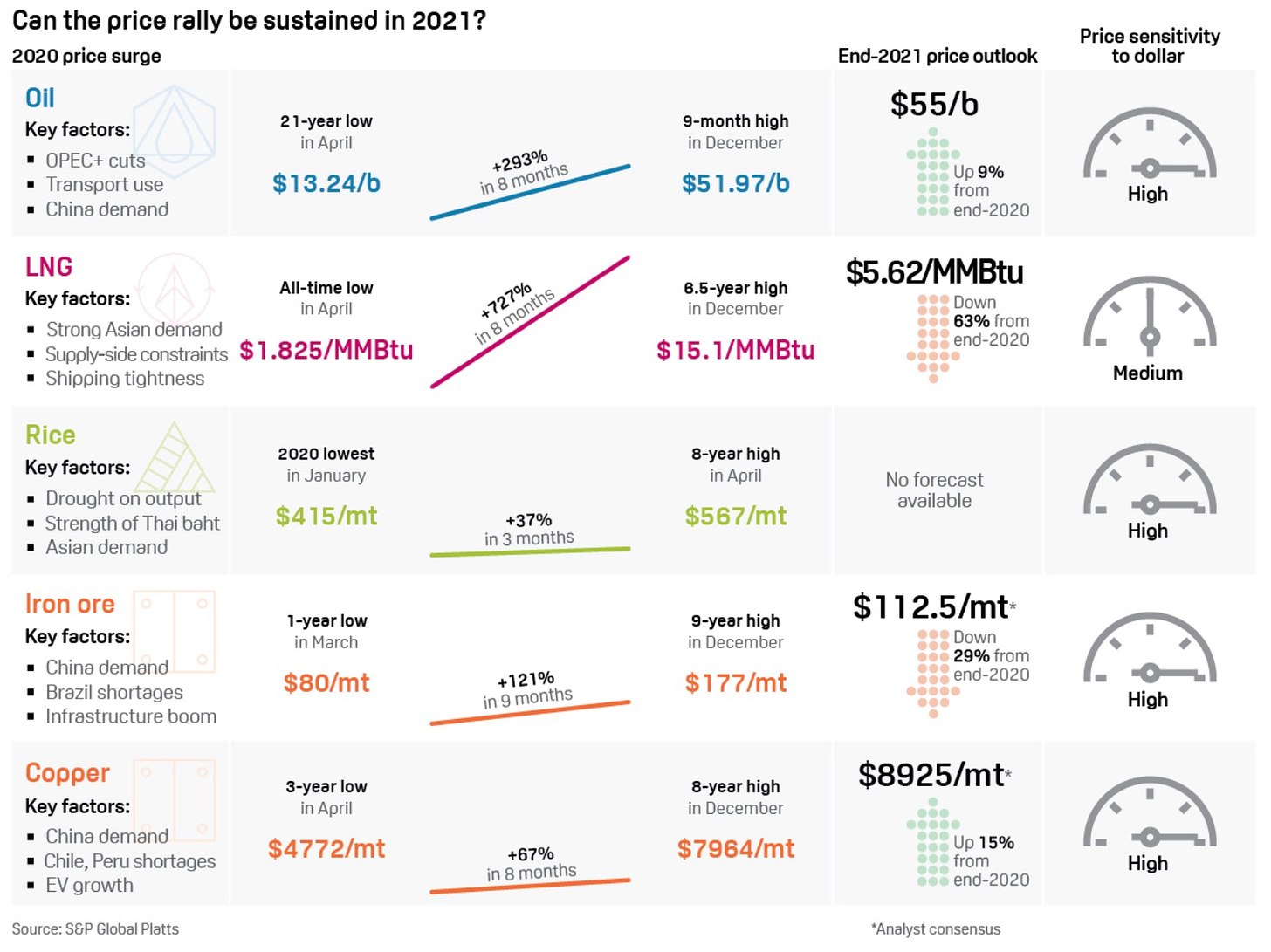

Take a look at commodity prices recently. They’re heading up. This chart from S&P is slightly terrifying:

All of which has people worried about a new “supercycle.”

What’s a supercycle? It’s a giant, sustained boom in commodity prices.

Which is a hop, skip, and jump from inflation.

I’m going to talk about this more in the coming weeks, but I want you to start putting an eye on it because it may be the most important challenge the Biden administration faces.

We are 31 days removed from a violent attempt to overthrow the U.S. government.

One of our two political parties is now objectively anti-democratic and functionally pro-authoritarian.

And fascism thrives on economic woe.

Whatever else happens, whatever other baubles catch your attention in politics, keep one eye on the broader economy. And pray that there are lots of smart people in the Biden administration who have both eyes on it, all day every day.

The battle to defend American democracy is going to have many fronts, from reforming our electoral systems to fighting against the proliferation of lies. There are logistical fronts, legal fronts, and cultural fronts.

But none of this will matter—none of it—if the country gets caught in an economic trap.

Heads up: We’ll have some Very Special Guests Wednesday and Thursday while I take a couple days off.

3. The RI School Experiment

Big NYT piece about how Rhode Island handled public schools:

At one of her regular televised Covid briefings in early December, Gov. Gina Raimondo of Rhode Island addressed the residents of her state to deliver a round of bad news. “I’m not going to sugarcoat this,” Raimondo said. “It’s getting scary in Rhode Island.” In the previous week, a daily average of 123.5 out of every 100,000 people in the state tested positive, which suggested, by that measure, that Rhode Island was the most Covid-infected region per capita in the country, which was to say the world. Stern and matter-of-fact, Raimondo urged viewers to do their part by not socializing; encouraged residents to take advantage of the state’s plentiful testing facilities; gave a thank-you to school leaders and teachers for all their hard work; and then paused for what seemed like the first time in 30 minutes, as if she considered all she had said so far to be preamble and she was only now getting to the heart of her message. . . .

As bad as the numbers were in Rhode Island, she was about to bear down on a conviction she had held since the spring: Schools must remain open for in-person learning.

Raimondo, who has two children in private school, has said that she sees school openings as a matter of equity. Governors in many red states insisted on school openings back in the fall — Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida, threatened to cut off funding in all but the hardest-hit regions if they offered only remote instruction — but perhaps no other Democratic governor has matched Raimondo’s dedication to the cause and her effectiveness in execution. When Rhode Island’s school-opening plan had fully rolled out by late September, only one public-school district, Pawtucket, was primarily remote.