The Overdue Downfall of Julian Assange

He was never an online Robin Hood, but a hapless hacker who endangered other people's lives.

For years now, the story of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has been one of wild disparities between image and reality: between the idea of the mad hacker king spinning governments around his fingers and the actual man squatting at London’s Ecuadorian Embassy, beseeching his benefactors to turn his Internet back on and mumbling imprecations to his cat. On Thursday, the reality won out: The government of Ecuador, apparently sick of Assange’s bad habits of authorizing the release of sensitive Ecuadorean documents as well as failing to keep his bathroom tidy, finally revoked Assange’s asylum claim. He was promptly arrested, and now faces extradition to the United States on “computer-related charges.”

There is no great need to rehash Assange’s life story, other than to say that he is an odious fool whose arrogance in service of a cockamamie ideology helped him to do a great deal of damage to America and its intelligence sources abroad as a witting tool of the world’s most evil regimes. As the curtain is pulled back, however, this may be a helpful moment to dispense with the final vestiges of the fantasy of Assange as some sort of online Robin Hood.

Only in the realm of fantasy was Assange ever the freethinking visionary or the cyberpunk demigod he styled himself to be. In his 2011 book Inside WikiLeaks, Assange’s former colleague Daniel Domscheit-Berg described how an organization supposedly committed to radical transparency committed act after act of ludicrous deception: baldly lying not just to credulous media outlets but even to their supposed martyrs and heroes, the whistleblowers who plied them with the documents that were their lifeblood. WikiLeaks’ submissions’ page, Assange and Co. assured them, was utterly anonymous and utterly safe: Impregnable, thanks to their computational might, to any cyber-attack that might endanger the leakers’ identities.

Only it wasn’t, not at all: “In fact, there was a chink in our security that we had overlooked,” Domscheit-Berg wrote. “When I approached Julian, he didn’t want to hear anything about the problem. … To create the impression of unassailability to the outside world, you only had to make the context as complicated and confusing as possible.” Assange’s disdain for the well-being of his own whistleblowers matched his lack of concern for the lives of the American military personnel his leaks regularly put in harm’s way. Nothing mattered but the crackpot agenda.

It was this agenda that made Assange so useful to America-hating governments the world over, from his salad days of leaking sensitive documents about the Iraq war to his willingness to mule Russia’s hacked emails from the Democratic National Committee and the Clinton campaign into the public eye in an effort to destabilize the 2016 presidential election. Everything was to be revealed—everything, at least, that didn’t happen to be in a foreign language: Domscheit-Berg admitted that WikiLeaks focused on the United States because “None of us spoke Hebrew or Korean” and “It wasn’t easy to gauge the significance of a document even when it was written in English.” Assange styled himself a courageous ideologue because he knew his way around a computer; what he really was was a dupe.

Will he face prison time? It’s too early to say. Some Tweeters in the know suggest that Assange’s willingness to publish ill-gotten materials might be insufficient to convict, given it appears Assange turned out to be too hapless a hacker to actually follow through on promises to help his leakers do their damage. At any rate, the five-year sentence prosecutors are seeking might not look too bad to a man who’s been hunkered down at an embassy for the past eight.

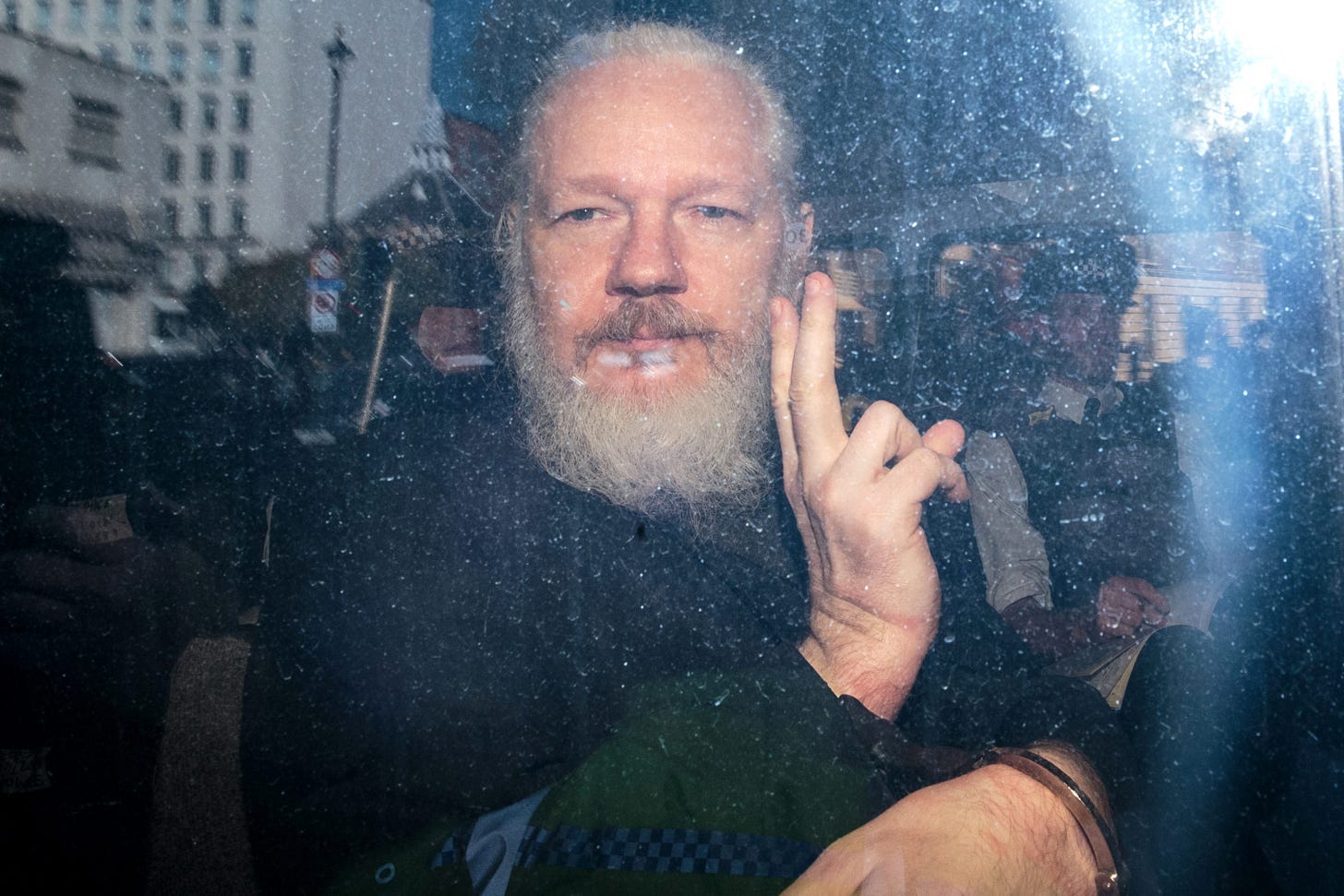

Regardless, the present moment provides an instructive example for observers both left and right. Behold the man, hunched and bedraggled, being carried—literally carried—from the embassy and bundled into a truck, bleating that “the UK must resist” his arrest, improbably clutching a copy of Gore Vidal’s History of the National Security State. This is Assange as he has always been: a goofy paranoiac utterly convinced of his own ideological supremacy, now stripped of the veneer of mystery and glamor, carefully cultivated online, that allowed some to view him as a hero. Sometimes it’s like this: a maniac clutches after some noble-sounding ideal in an effort to convince the world he’s the only one who’s really sane. Be advised that there are more of these types out on the range than Julian Assange.