The Pandemic and the Great Unbundling (and Rebundling) of American Schools

Learning from the last year and a half to create a more parent-directed and pluralistic system.

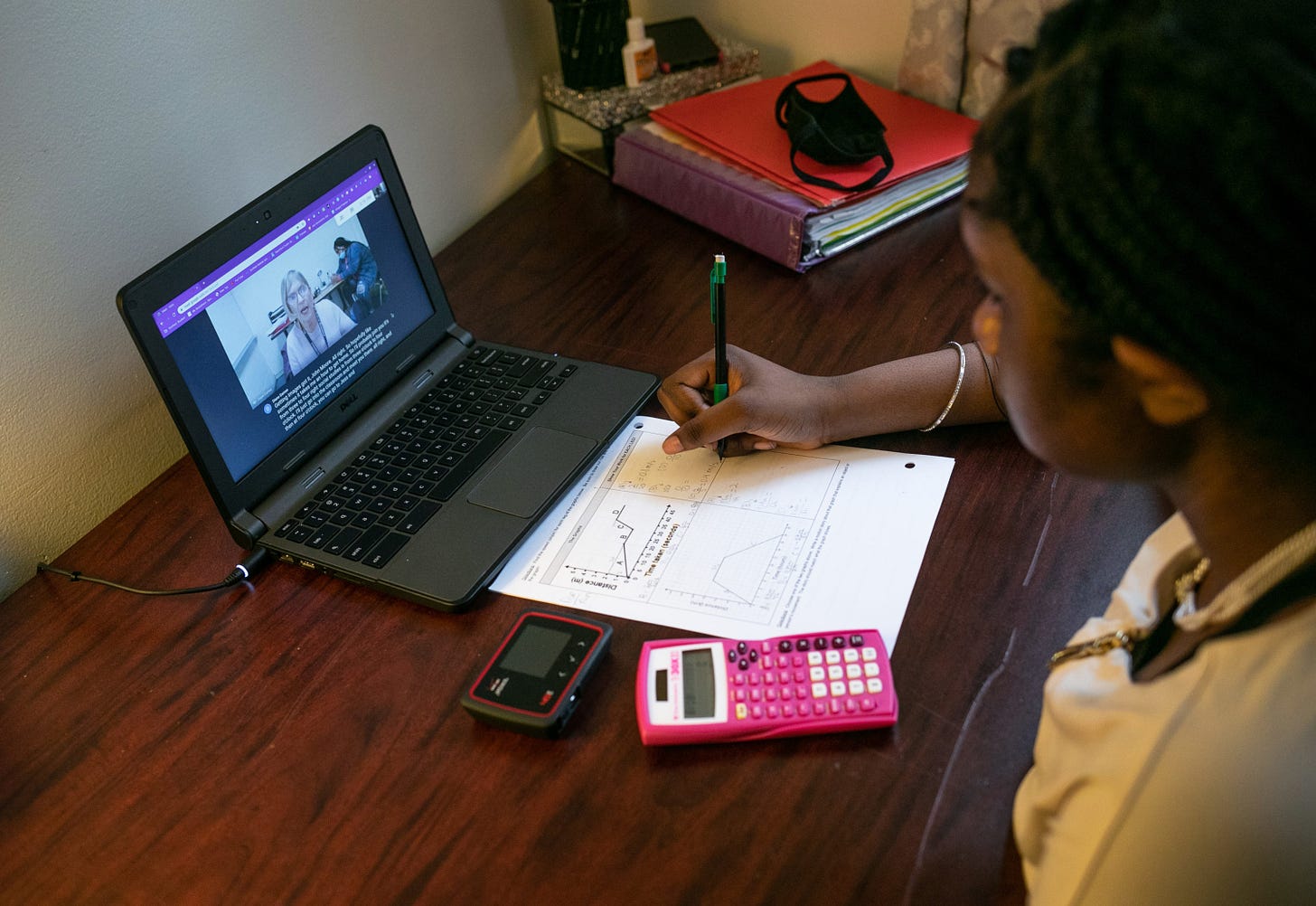

The COVID-19 pandemic put parents in charge of their children’s education in ways few imagined. While the stories of children falling behind and becoming depressed, and of the stresses put on families trying to cope with learning during lockdown, have been widely reported, the pandemic’s disruptions to education may have wide ripple effects. It scrambled the familiar division of formative responsibilities carried out by home, school, and the other community enterprises that comprise local civil society. In doing so, it unbundled the traditional place-based, K-12 whole school model with adults and students in a building for teaching, learning, and other support.

Families were compelled to think differently about school, to recreate school. The boundaries between home, school, and other local institutions became more elastic, even porous. The result is that families, students, teachers, and taxpayers have created a more parent-directed, pluralistic K-12 system.

Unbundling Schooling

Typically, we think of school as a place—a building on a piece of land—where adults offer young people a package of services—primarily teaching and learning, but other amenities like meals, recreation, tutoring, and after-school care. COVID-19 separated these bundled services into discrete ones—e.g., regular teaching and learning via computers at home; meals provided by community organizations like United Way; tutoring organized by homeschool co-ops.

Parents were faced with a new, challenging responsibility: create a learning and support program for your child, choosing from old and new providers. Parents scrambled to rebundle the COVID-19 unbundled learning and support services their child needed. This fostered parent self-agency—their ability to control their child’s education—though not without pandemic-induced confusion, frustration, and dismay.

Survey reports document this change. From December 2020 to January 2021, Tyton Partners conducted an online survey of about 3,000 parents from public, charter, private, and homeschooled students. (Full disclosure: Tyton Partners, like some of the other organizations named in this article, receives financial support from the Walton Family Foundation, where I am a senior advisor.) The survey sample was screened to be nationally representative by income levels, region / locale, and children’s grade levels. Nearly 15 percent of the respondents said they had changed their child’s school due to the pandemic, with 12 percent also enrolling their child in supplemental learning groups. Tyton estimates these shifts produced a 2.6 million enrollment decrease in district and private schools, with charter schools, homeschooling, micro schools, and other new approaches gaining enrollment.

National shifts in schooling from pre-COVID-19 vs. fall 2020, extrapolating from the Tyton Partners survey. (Courtesy Tyton Partners)

Gallup reported related findings last summer. Parents saying they’re “completely satisfied” with public schools dropped 9 points between August 2019 and August 2020, from 41 percent to 32 percent. The percentage of parents who said they expected to homeschool their children nearly doubled, from 5 percent to 10 percent, with expected public school enrollment decreasing 7 points, from 83 percent to 76 percent.

U.S. Census data also supports the homeschooling surge during the pandemic—from 5.4 percent of households in spring 2020 to 11.1 percent in fall 2020, even after clarifying the question so households reported true homeschooling rather than virtual learning through a public or private school. African-American households registered a fivefold increase, from 3.3 percent to 16.1 percent.

The education reform nonprofit EdChoice has surveyed parents monthly since the pandemic began. Over time, parents developed a more favorable view of homeschooling. In April 2021, 64 percent of parents said they hold “somewhat” or “much more favorable views on homeschooling,” up from 52 percent a year earlier.

The Tyton survey suggests a caution regarding homeschooling, especially if the higher rates become permanent. More than half (55 percent) of parents earning less than $35,000 annually switching to homeschooling perceive it as “free” and don’t spend money on it. But only 7 percent of parents earning over $150,000 per year see it as “free,” with just over half spending in excess of $500 per month on it and almost a third spending more than $2,000 per month.

More Alternatives

What other alternatives are parents choosing?

The best known are pods, micro schools, and virtual schools.

Pods (sometimes backronymed as “Parent Organized Discovery Sites”) are small groups of children gathering in person or virtually. Programs are initiated by a variety of actors—local government, nonprofits, parents, corporations—using volunteers or hiring teachers and other adults to supervise programs. They supplement formal school with special services, including tutoring, childcare, and after-school programs that mix academics and extracurricular activities. Families pay directly “out of pocket” for pods or receive them as employee benefits. Some pods provide scholarships for low-income families. Other approaches include using state or local tax dollars or support from nonprofit and philanthropic organizations.

San Francisco opened 84 pods called community learning hubs run by the city, Mayor London Breed’s response to a dispute with the school district’s closing policies. The hubs served around 2,400 children, about 96 percent racial minorities.

In Columbus, Ohio, the YMCA offered pods for students ages 5 to 16 who were attending school virtually. Students arrived as early as 6 a.m., with learning sessions starting at 8 a.m.

In Minnesota, the Minneapolis-based African American Community Response Team created the North Star Network of community pods using Zoom. They supplemented online learning offered by schools, providing a quiet learning space, technology, and tutors.

JPMorgan Chase offered eligible employees discounts on virtual tutors and pods accessed through its employer-sponsored childcare provider, Bright Horizons. The firm also opened its fourteen childcare centers for employee children as a no-cost place for remote learning with supervision.

Organizations are helping families navigate this new terrain. Websites like SchoolHouse, LearningPodsHub, and Selected for Families assist with starting pods, organizing teachers and tutors for them. SitterStream offers babysitting and tutoring to students, individually or in pods. It has partnerships with small and large businesses servicing employees, with Amazon one of their corporate clients.

Child participation in learning pods required parents make special arrangements and financial sacrifices. The Tyton analysis reports nearly 30 percent of parents worked different hours to accommodate their child’s pod participation. More than 20 percent said they reduced personal spending, took on additional jobs, or used savings to pay for pods. These changes were relatively consistent across income levels.

Tyton estimates that overall annualized parent spending on education in fall 2020 for both nonpublic and out-of-school activities and products was $232 billion, a one-year increase of nearly $20 billion or 10 percent. The primary expense was for expanding supplemental learning pods. “Parent investment in homeschooling also saw a sizable increase,” the report’s authors note, “growing nearly 70 percent, from $7 billion to $12 billion.”

Micro schools are another alternative. They reinvent the one-room schoolhouse, enrolling fifteen students or less from three to six families. They might employ one teacher, or alternatively, parents teach, hiring a college student or other “grownup” to assist.

Prenda is an Arizona-based network of micro schools, growing from seven students in 2018 to over two hundred schools and three thousand students. School can be held in homes or public spaces like a community center or library. They are led by a Prenda Guide, a trained mentor, not necessarily a certified teacher. During the pandemic, Prenda expanded to Colorado.

Virtual schools are a third example. Florida Virtual School is an accredited, online tuition-free school founded in 1997. It employs Florida-certified teachers and works with public, private, charter, and homeschool families and school districts nationwide. From July through September 2020, it saw over 231,100 new course enrollments—a 57 percent increase—in its open-registration, part-time program.

Philanthropy has stepped up support for these efforts. The VELA Education Fund awards microgrants of up to $25,000 to students, families, and educators innovating outside the traditional education system. For example, Zucchinis Homeschool Co-op is a parent-led pod serving 4-to-10-year-olds, including the younger siblings of students at the LIFE School, an accredited, project-based high school in downtown Atlanta. VELA also awards grants of up to $250,000 for programs that expand to serve more families. Prenda’s micro-school expansion to Colorado was funded by VELA.

How Sticky Are the Changes?

Evidence suggests some of these changes will stick beyond the pandemic.

Lawmakers in nearly a third of the states have proposed bills to establish or expand a variety of taxpayer-funded programs to continue these new approaches. Governors are using federal COVID relief funds in inventive ways. For example, Idaho Republican Governor Brad Little created a new $50 million Strong Families, Strong Students Initiative. Eligible families can receive $1,500 per student, with a maximum of $3,500 per family. Money can be used to purchase eligible educational materials, devices, and services. Other governors have created similar programs.

State policies enacted over the last three decades to protect or promote school choice provide other ways to support these approaches. Today, 29 states (plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) offer parents public dollars for expenses associated with enrolling children in alternatives to traditional public schools. These include school vouchers or scholarships, education savings accounts, tax credit scholarships, individual tax credits and deductions, micro schools, and more.

Moreover, parents are eager to continue their use of these alternatives.

In a February NPR/Ipsos poll weighted to match the nation’s demographics, almost 3 in 10 parents said they would likely stick with remote learning indefinitely, including about half of the parents currently then enrolled in remote learning.

And in April, Beacon Research conducted a poll, also weighted to national demographics, to gauge reactions to the massive infusion of federal education funding in the recent COVID relief and stimulus legislation. Nearly 6 in 10 said they see funding as “open[ing] the door to making bold changes in public education.” Over 6 in 10 say this use of funds could be either “extremely effective” or “very effective” in helping students by “expanding high-quality tutoring programs”; “creating more school options, like charter schools [and] learning pods”; and “providing direct grants to parents of $500 per child.”

After surveying a thousand public and private school parents on how the pandemic affected their view of schools, longtime pollster Frank Luntz of FIL Inc. expressed surprise: “Never in my lifetime have so many parents been so eager for so much educational change.”

https://www.twitter.com/FrankLuntz/status/1327010143695847425

Finally, as pandemic precautions wind down in many workplaces and public spaces, schools will have the options of returning to pre-COVID conditions or of experimenting with keeping some of the arrangements that were adopted during the crunch of crisis. It may be that some of the techniques developed over the last year and a half can help to strengthen education while lowering costs. A RAND Corporation survey using their American School District Panel composed of leaders of more than 375 school districts and charter management organizations found that 1 in 5 are considering a remote-school option after the pandemic ends.

An example is Cobb County, Georgia, serving over 112,000 students—the second-largest school district in the state and the twenty-third-largest nationally. Superintendent Chris Ragsdale announced in March that the district would enact a classroom choice program for the 2021-22 school year. A variety of partially or fully digital programs are available, including “the new Cobb Online Learning Academy for online learners in grades 6-12, local school based online learning for students in grades preK-5, Cobb Horizon Academy as an alternative school for online learners, and the Cobb Virtual Academy for part-time online learners.”

The creativity and entrepreneurship seen in education over the last year and a half is characteristically American and impressive, even if driven by urgency and exasperation. It is reinventing some of the fundamental formative institutions of local civil society. If we are thoughtful and deliberate in deciding which changes to extend and how, we may find that the short-term exigencies of the pandemic have left behind long-term improvements offering our children a more parent-directed education that better prepares them for opportunity, success, and responsible citizenship.