The Pandemic and the Noise We Need

“Where is everybody?”—the new Fermi Paradox of cities under lockdown.

“Silence reigned over the before tumultuous but now deserted deck.” –Moby Dick

San Juan, Puerto Rico Wanda Vázquez was the first U.S. governor to impose a stay-at-home mandate as the global death count for COVID-19 rose exponentially. On Sunday, March 15, she signed an executive order closing businesses across Puerto Rico, establishing a curfew, and generally ordering people to stay home. Streets that hours earlier were filled with spring breakers, tourists, and local beachgoers fell quiet. Noise itself seemed to be canceled. The specific provisions of the lockdown declaration held that all nonessential workers stay home except for trips to the grocery store, pharmacy, bank, and medical appointments. More than 100 people were arrested for violating the nightly 9 p.m.-to-5 a.m. curfew during just its first five days. The lockdown grew more strict as the initial two-week executive order was extended: Starting March 31, the curfew began at 7 p.m., supermarkets were ordered to be closed on Sundays, and the cars on the road were limited based on license-plate numbers. Even as the other states and territories went on to issue their own much-delayed stay-at-home orders, Puerto Rico’s has remained the most aggressive. Most of these restrictions seem arbitrary—and they have certainly felt futile as the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths on the island has risen. Moreover, the orders have caused confusion and uncertainty, leading to the first coronavirus curfew-related lawsuit, filed this week by the ACLU arguing that some of the restrictions are unconstitutional. Even police have been detained for violating the curfew. The effect on the community—on the scenes and sounds of Puerto Rico—has been profound. Except for the occasional siren and dogs, day to day the streets are mostly quiet. In Condado, a tourist-friendly area, police often outnumber pedestrians coming and going from the pharmacies and grocery stores. Immediately following the initial lockdown declaration, videos circulated of cops pulling people off the beaches, and hazard tape now restricts access points. As people isolate themselves, going to great lengths to maintain distance and avoid arrest, the result is emptiness, a void. In 1950, physicist Enrico Fermi exclaimed “Where is everybody?” while at lunch with his colleagues, puzzling over humanity’s existential loneliness. It became known as the Fermi paradox: The bizarre fact that we have had no contact with extraterrestrials or observed other advanced civilizations even though there’s been ample time for them to have made themselves known. Humanity resists the idea of being alone at a cosmic level. “The Fermi paradox is sometimes known as the Great Silence,” writes Ted Chiang in his story by that name. “The universe ought to be a cacophony of voices, but instead, it’s disconcertingly quiet.” Chiang’s story—a story of survival told from the perspective of an African gray parrot—creates a parallel between humans seeking to communicate with extraterrestrial life and the bird attempting to be heard here on Earth. Both species have “contact calls.” Humanity’s “contact call” is the Arecibo message—so called because it was broadcast by the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. In 1974, it transmitted our attempt to tell extraterritorial life elsewhere in the galaxy that we are here: https://soundcloud.com/nadiadrake3/arecibo-message-1974 I came to Puerto Rico for a number of reasons, foremost among them to make a pilgrimage to the observatory. But it has been closed in accordance with the governor’s order. There is some hope though: While the observatory may sit empty, the experts are at least getting back to their projects following the initial interruption. According to a statement from the observatory’s administration, “We are happy to announce that starting [April 1] we will be restarting all previously scheduled and approved observations. . . . All observations will be performed remotely or absentee, no in-person observations will be allowed.” The lonely reality of the lockdown somehow suits the deeper loneliness of the mission of Arecibo: observing silence. “When the Arecibo telescope is pointed at the space between stars,” Chiang writes, “it hears a faint hum”:

Astronomers call that the “cosmic microwave background.” It’s the residual radiation of the Big Bang, the explosion that created the universe fourteen billion years ago. But you can also think of it as a barely audible reverberation of that original “Om.” That syllable was so resonant that the night sky will keep vibrating for as long as the universe exists. When Arecibo is not listening to anything else, it hears the voice of creation.

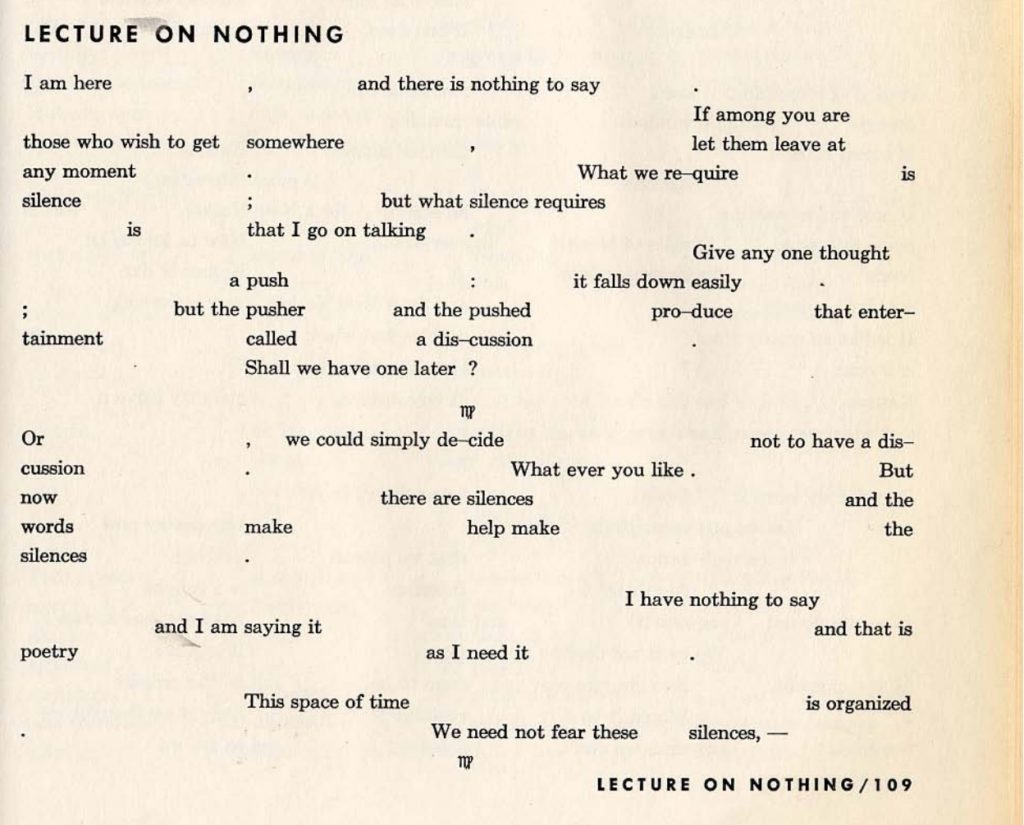

Chiang’s whole story is acutely relevant to our present moment, but I would point to one other line: “It is no coincidence,” he writes, “that aspiration means both hope and the act of breathing.” There is a third definition, in medicine, applicable to our current plight: aspiration “is the abnormal entry of food or liquid into the windpipe and subsequently into the lungs.” If you aspirate and the coronavirus infects cells below your voicebox, it can lead to pneumonia and all manner of complications. This is especially a concern for the immunodeficient, and there is more risk of it happening during sleep. Our main mechanism for breaking silence and the time we spend most in silence are when we are most vulnerable. From roughly 2014 to 2016, there was trend piece after trend piece concerning the commodification of silence. Everything seemed to be getting louder, and culture writers mourned the state of bustling public spaces that had become inhospitable auditory hells. Noise is jarring and difficult to escape. Enough noise or a sound loud enough can even kill you. Silence is now supposedly a luxury only for the elite who can afford exorbitantly priced headphones and getaway retreats and other capitalist solutions to the problem of discordant sound. Shouldn’t we then in some sense benefit from this mandated prolonged break from crowd-generated auditory overstimulation? Some commentators have observed that one beneficiary of the outbreak is wildlife. Humanity at standstill has caused a downward trend in greenhouse-gas emissions and a number of other side effects typical to the genre of ruin-porn wherein animals run the streets and plants reclaim buildings. An abundance of natural silence fits this apocalyptic sense of the world. Gordon Hempton, a renowned acoustic ecologist and “silence activist,” has a few thoughts on the matter. Hempton has spent years tracking silence in nature and the encroachments of modernity’s ever-increasing racket. He lives outside of Seattle, Washington, where the first U.S. cases of the coronavirus were reported. The entire state is under lockdown. In a phone interview, Hempton told me that what we saw leading up to the outbreak was a triumph of belief over information. Now the information is inescapable. “This is what happens when you get the forecast and science tells you something and you refuse to believe it.” But “it’s experience that forms our belief and what is meaningful and what is worthwhile, not information. We would like to think that if we get enough information, we’re going to choose the right decision.” There are many scenarios where we have all the information we could possibly want, but “we don’t have the belief—and belief is what causes change.” Hempton recognizes that the sudden silence now in our cities can be eerie and daunting, but “as uncomfortable as we might feel when we’re alone in silence, we need to spend some time there. We need to have it to ground us.” The longer that people are home and deconditioning from the sensory blitz of heavy commutes and loud advertisements, the greater the reinvigoration of “the sonic detail of life.” Hempton believes that “it’s going to be much more vibrant,” that this time for many people will be an opportunity to “open up a new auditory horizon.” Most people, Hempton says, have never spent prolonged time truly listening and there is a misunderstanding about what that entails. Listening is not about focusing your attention; when you focus on something you are operating under a controlled impairment. “Listening simply means taking everything in,” he explains, “especially the background sounds—because it is the faint sounds which have been the driving factor of hearing evolution, because that is when we get the arrival of the new information.” Sound is a stimulant. Too much can become overwhelming. You can be desensitized and need it like caffeine. Why then is this mandated reprieve from the persistent auditory onslaught so frightening and unnerving? “You start to hallucinate,” Hempton says. “After a period of time [you’re] ready for information, the mind still needs stimulation. In a prolonged position of no information, the brain will create its own stimulation.” This is part of why being silenced is so much worse than natural silence. For one to benefit from silence, or any extreme environment shift, one should have agency and a choice in the matter. We’re all familiar with the image of the astronaut untethered from the spaceship and floating into the void, lost to the static, the radio eventually cut silent. Silence is one of Alfred Hitchcock’s most powerful devices in triggering the “startle reflex”—building suspense through absence, then throttling the viewer with sharp sound as the murderer appears on screen. One of the highest-grossing movies of 2018 was John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place, a horror flick premised upon an invasion of aliens summoned by noise. We have been conditioned by horror movies and dystopian tropes to associate silence with fear and unseen or unheard threats waiting for us, coming for us. Silence, without agency or the free will to choose it for yourself, suggests the grave. It can be a harbinger of death itself. To borrow from the children’s book The Phantom Tollbooth, we now find ourselves in the Valley of Sound—a terrifying place locked in silence by the Soundkeeper who has taken all sound and stowed it away in a fortress. The protagonist, Milo, smuggles a small word out from the confines of the walls to the protesting residents of the valley. The word is shot with a cannon at the fortress, which comes crumbling down, freeing noise from the vault. The lesson is that silence is not the answer, but that there should be more gratitude for language, to protest when it is taken or restricted by those in power. One of the difficulties of discussing silence is that it is an absence, much like zero in math. What then does the Valley of Sound look like? The New York Times has been documenting “The Great Empty”—the normally bustling thoroughfares now desolate. Similarly, photographer Noah Kalina has been touring landmarks through live video feeds and made a thread of images of the deserted common areas that were, until recently, home to high traffic. https://twitter.com/noahkalina/status/1242114225121693696 As the primary outbreak site of the pandemic in the United States, New York has fallen more and more under the hush of stillness. Broadway will sit quiet until at least June. The advertisements in Times Square flash their commercial urgencies to no one. The streets will soon have fewer and fewer horns, replaced instead by the sirens of ambulances. The same is true for cities around the globe: From Rome to Bogota, the quietude speaks to the common understanding that the crisis supersedes all else. Paradoxically, we are being unified by efforts to separate and protect each other with distance. It is as if John Cage has cast some kind of enchantment or hex over us. 4’33’’ has been reversed; there is no audience in the auditorium to fill the performance and make it whole. In Germany, that vacancy was seen and felt by a digital concert performed by the Berlin Philharmonic. “The most instructive thing about the Berlin concert,” wrote Alex Ross in the New Yorker, “was how it dramatized what technology cannot supply: the temporary bond of purposeful community that forms under the spell of live music. The final silence was a vacuum crying to be filled.” But people are still applauding. In Italy, despite the devastation of the pandemic, videos are still circulating of the quarantined taking to their balconies to sing in communion with each other. Every night at 7 p.m. New Yorkers join in an ovation for the essential workers who have their backs. Barcelona, Brasilia, and Brooklyn are all doing the same, coming together-apart in applause for healthcare workers. Puerto Ricans have joined in, too, protesting the silence and applauding the emergency responders and medical professionals: https://twitter.com/ruthyoest/status/1242620344856383488 And we’re not just shouting off balconies into the void: Telephone companies have seen a spike in phone calls and text messages. “We’ve had 800 million calls a day. That’s double the amount of calls you would have on Mother’s Day, which is the busiest [Sunday] of the year,” Verizon CEO Hans Vestberg told CNBC. It is not silence itself we are pushing back against, it is the isolation we feel when we lack the intimacy of closeness. “If you are not being touched at all,” writes Olivia Lang in The Lonely City, “then speech is the closest contact it is possible to have with another human being.”

John Cage, August 1959 Some commentators would have you believe that the pause of industry and altered state of reality should be an opportunity to hustle even harder on side projects and self-improvement. This is just another form of resisting the quiet, a scam of fetishized labor seeking to recreate the patterns of noise we have lost. Perhaps, with that in mind, we should heed those who don’t resist the hush but choose to inhabit it, those who are, like Hempton, truly listening—“taking everything in.” We should be able to recognize the different silences we face, and that not all of them merit protest. There is a timeline to the silences that have arisen from the coronavirus: the silence of the virus itself, the silencing of the doctors who sought to warn the world, the silence of leaders who knew what was coming, the resulting silence in the vacated public squares and offices, and the final silence of those who will die. Each of these is a unique type of absence that adds to the definition of silence. Yet another paradox is that each is their own amalgamation of danger, threat, and fear. While we might think of COVID-19 as hardly silent—after all, a terrible, dry, unproductive cough is a common symptom for patients with suffering lungs—the growing number of confirmed cases in carriers who are asymptomatic suggests that the coronavirus moves most efficiently and lethally in stealthy silence. And then there are Chinese officials’ efforts to destroy evidence of the virus’s presence and the imminent threat early on. The silence demanded by dictators is a silence entirely different from the environmental quiet—it is a brittle, brutal silence, a silence of reticence and self-preservation, a silence of deceit. Since 1987, the “SILENCE = DEATH” project, founded to raise awareness for the AIDS epidemic, has been invoked in many different political circumstances. But we must be cognizant of the context from which that famous image and slogan arose. Avram Finkelstein, the designer of the poster, wrote the book After Silence: A History of AIDS through Its Images, and described the origin of the phrase and its political implications: “We talked about the deadly effects of passivity in crises, communal silence and the nature of political silencing, silence as complicity, and scenarios where bystanders became participants without intending to be.”

The Hirschhorn Museum, Washington D.C. http://www.washingtonblade.com/2018/02/21/act-exhibit-opens-hirshhorn-museum/ (Photo by Ted Eytan via Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])Today, in a new context, we are once again facing a silent enemy and silence as an enemy. Mathew Rodriguez has written a decisive account of the similarities between the AIDS and COVID-19 epidemics: “HIV and [the coronavirus] have little in common as to how they are transmitted and how they affect the human body on the inside. But, in the way that they affect the body politic, the citizenry, they have dusted up many of society’s worst impulses: the need to blame, to criminalize, to lock each other up.” He points out parallels between the political responses to the two diseases, as well as the isolating effects of the viruses themselves. “In the end,” Martin Luther King famously said, “we will remember not the words of our enemies but the silence of our friends.” In our current situation, it may be our leaders’ silence that will haunt us the most—the silence of those who neglected to sound the alarm, to cut through the other noise. Our current state of silence is a price we are paying for their neglect. In Deaf Republic, Ilya Kaminsky’s award-winning poetry collection, a town under military occupation goes deaf in defiance and creates its own language to communicate outside of the norms of speech to evade the control of the soldiers. Kaminsky writes: “The deaf don’t believe in silence. Silence is the invention of the hearing.” The paradox for us is that we should and must protest the silence of our leaders while preserving the silence in public spaces. Kaminsky’s poetry is a testament to the fact that we can inhabit the silence and protect each other while resisting isolation and loss of intimacy. After all, the thirteenth-century Persian poet Rumi tells us, “silence is the language of god, all else is poor translation.” And what poor translators we make.