The Politics of Overturning <i>Roe</i> Are Bad for Republicans

The polling is conclusive and overwhelming.

On Tuesday, at a Republican press conference, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell was asked three times about the big story of the week: A draft Supreme Court opinion, leaked to Politico, that exposed the Court’s intention to overturn Roe v. Wade. McConnell was furious about the leak. But each time reporters asked him to talk about abortion, he refused to engage.

Morally, this reticence seems bizarre. For half a century, Republicans have campaigned on promises to expunge Roe. They said millions of unborn lives were at stake. Now victory is at hand, but McConnell won’t talk about it. Why not?

The answer is simple: He knows this issue is bad for his party. Roe infuriated pro-life Americans and made pro-choice Americans complacent. Republican candidates could use the issue to rile up their base without risking an electoral backlash. But if Roe goes down, Americans who want to keep abortion legal will have to vote that way. And those Americans are a political majority.

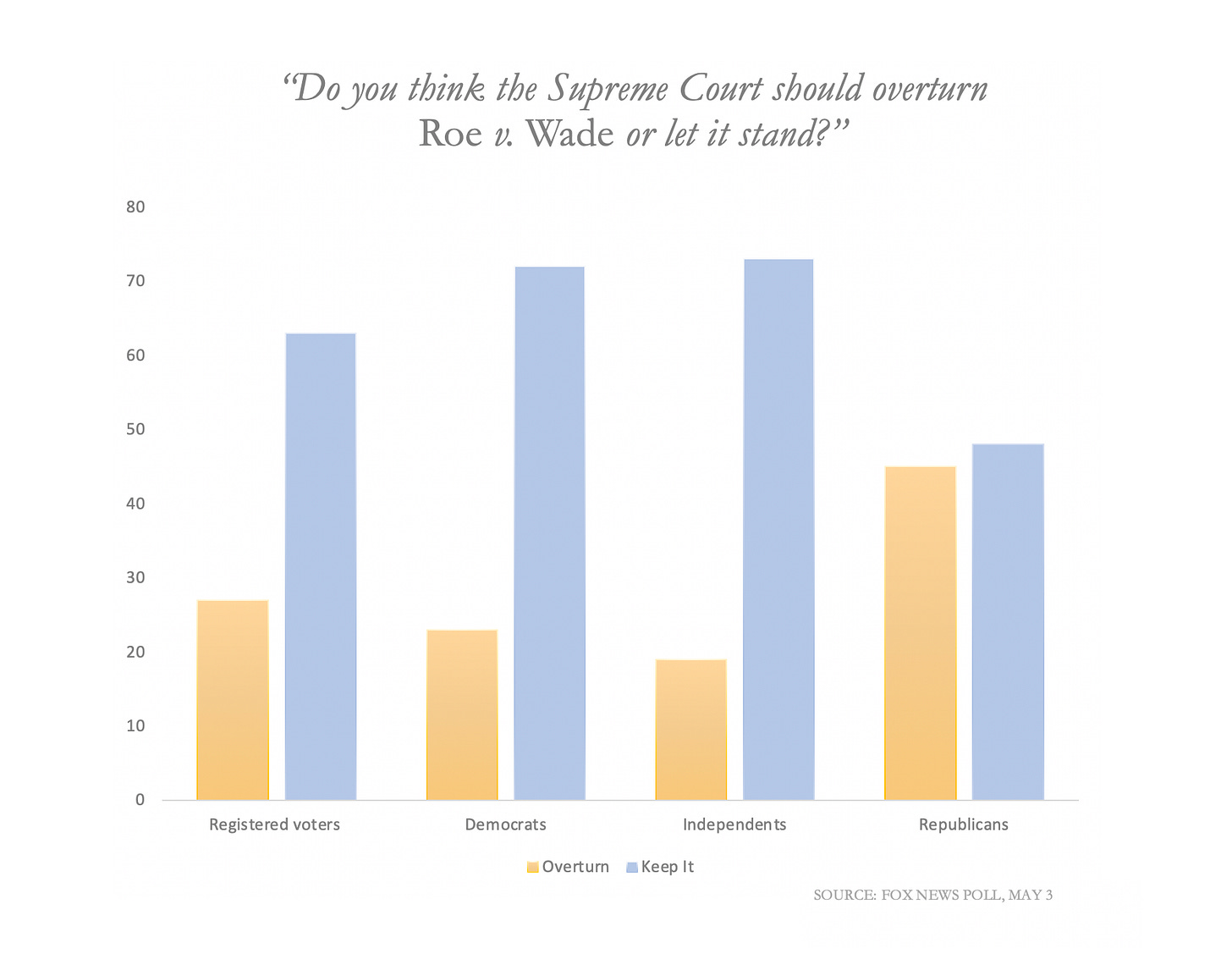

Polls taken in the last six months paint a clear picture of the coming storm. Few Americans expected Roe to be overturned, and most didn’t want the Court to do it. The numbers vary, but the pattern is consistent: Between half and two-thirds of the public wants to keep Roe, and Roe supporters outnumber Roe opponents by about 2-to-1.

Surveys conducted on Tuesday, after the draft opinion was leaked, conform to this pattern. And a new Politico poll indicates that if the Court dumps Roe, supporters of legal abortion will retain their dominance and turn to Congress for protection. Nearly 50 percent of voters want Congress to pass “a bill to establish federal abortion rights granted through Roe v. Wade, in case the Supreme Court overturns the ruling.” Only about 30 percent oppose that idea.

In poll after poll (with rare exceptions), most Americans say most abortions should be legal. When they’re asked what states should do if Roe is overturned, people repeat that position. And when they’re asked whether states should make it harder or easier to get an abortion, more say it should be easier than harder.

It’s not that people don’t care about unborn life. Many do. In a December Economist survey, 46 percent of registered voters agreed fully or partially that “abortion is the same as murdering a child.” In a February Politico poll, 42 percent supported “promoting the idea that abortion ends a human life.”

But many of these people are also open to pro-choice arguments. In the Economist poll, for instance, 80 percent of Republicans agreed that abortion was murder, and more than 60 percent agreed strongly with that statement. Yet in the same survey, 43 percent of Republicans said they could “support a candidate who has a different opinion than you on whether abortion should be legal.” Clearly there’s some overlap, since those numbers add up to more than 100 percent. For some people, the idea that abortion is murder reflects genuine revulsion, but it’s also negotiable as a matter of policy.

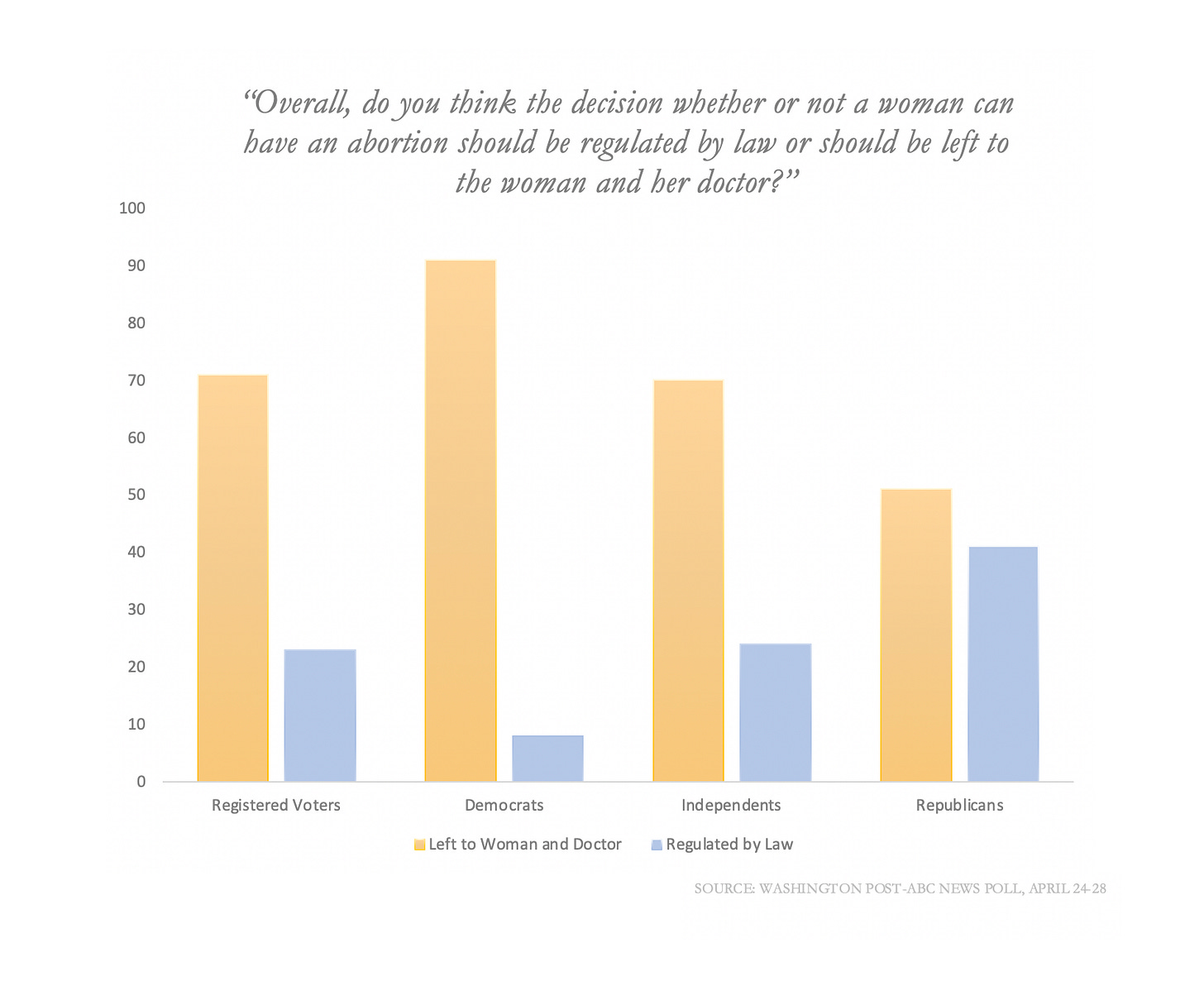

Meanwhile, pro-choicers have a message with enormous resonance: that abortion policy is fundamentally about who gets to decide whether to end a pregnancy, not about which decision is made.

More than 70 percent of registered voters say abortion should be “left to the woman and her doctor” rather than “regulated by law.” Two-thirds of likely voters say “the government should not interfere in personal matters like reproductive rights.” Every year, the Knights of Columbus sponsors a poll that asks Americans whether they’re more pro-life or pro-choice. The Knights are devoutly pro-life. But almost every year, their poll finds that most Americans are pro-choice.

Nobody knows for sure how Roe’s demise would play out politically. But all the evidence suggests it would help Democrats. To begin with, voters, and independents in particular, trust Democrats on this issue more than they trust Republicans. In polls, the margin is about 10 points. In a year when most of the big issues are hurting Democrats, this issue works in their favor.

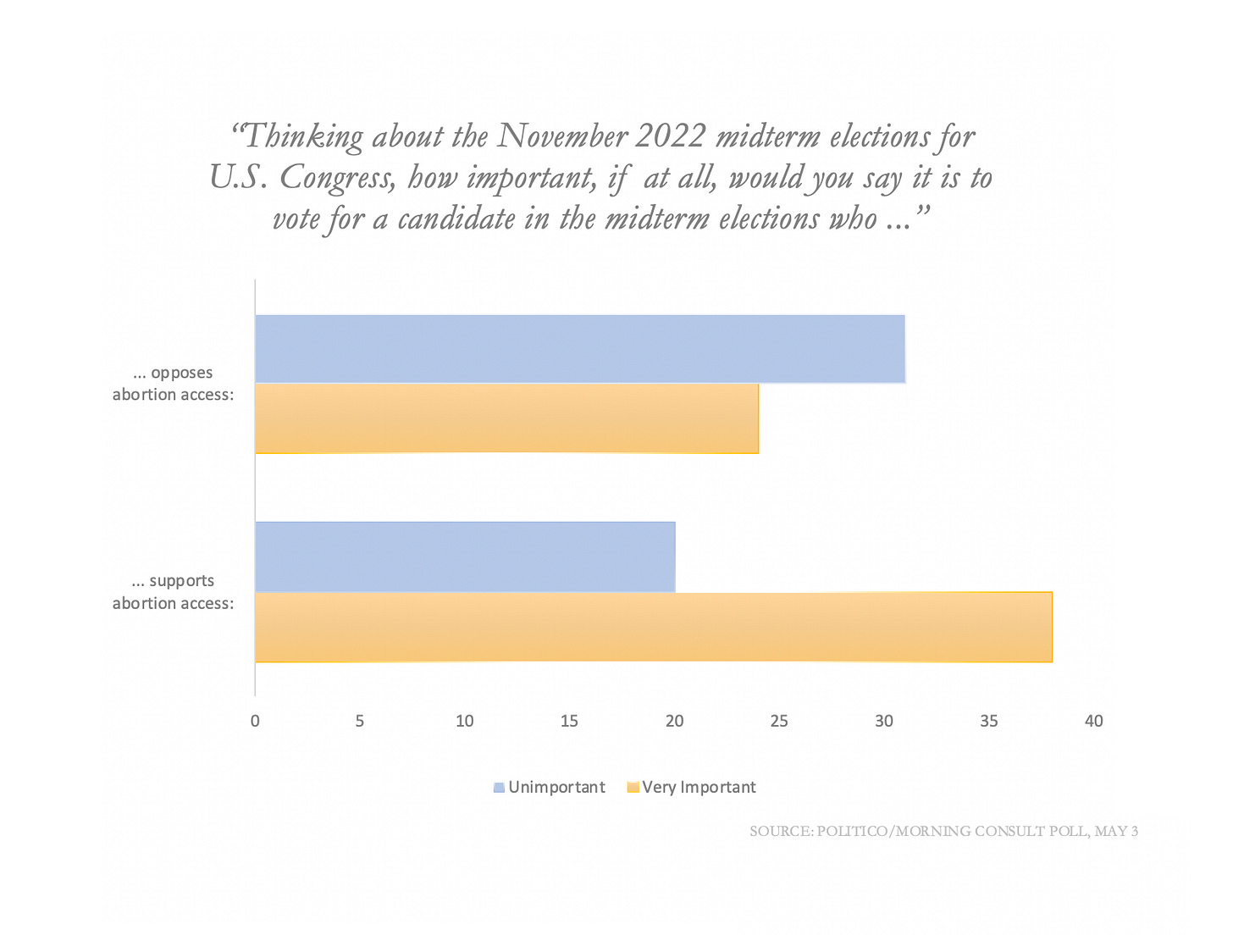

Second, Democratic voters are slightly more likely than Republican voters to insist that a candidate agree with them on the issue. The gap ranges from 4 points to 8 points. The new Politico poll confirms that this gap persists when respondents are categorized by abortion views rather than by party. Pro-Roe voters are more likely than anti-Roe voters to demand that a candidate share their position.

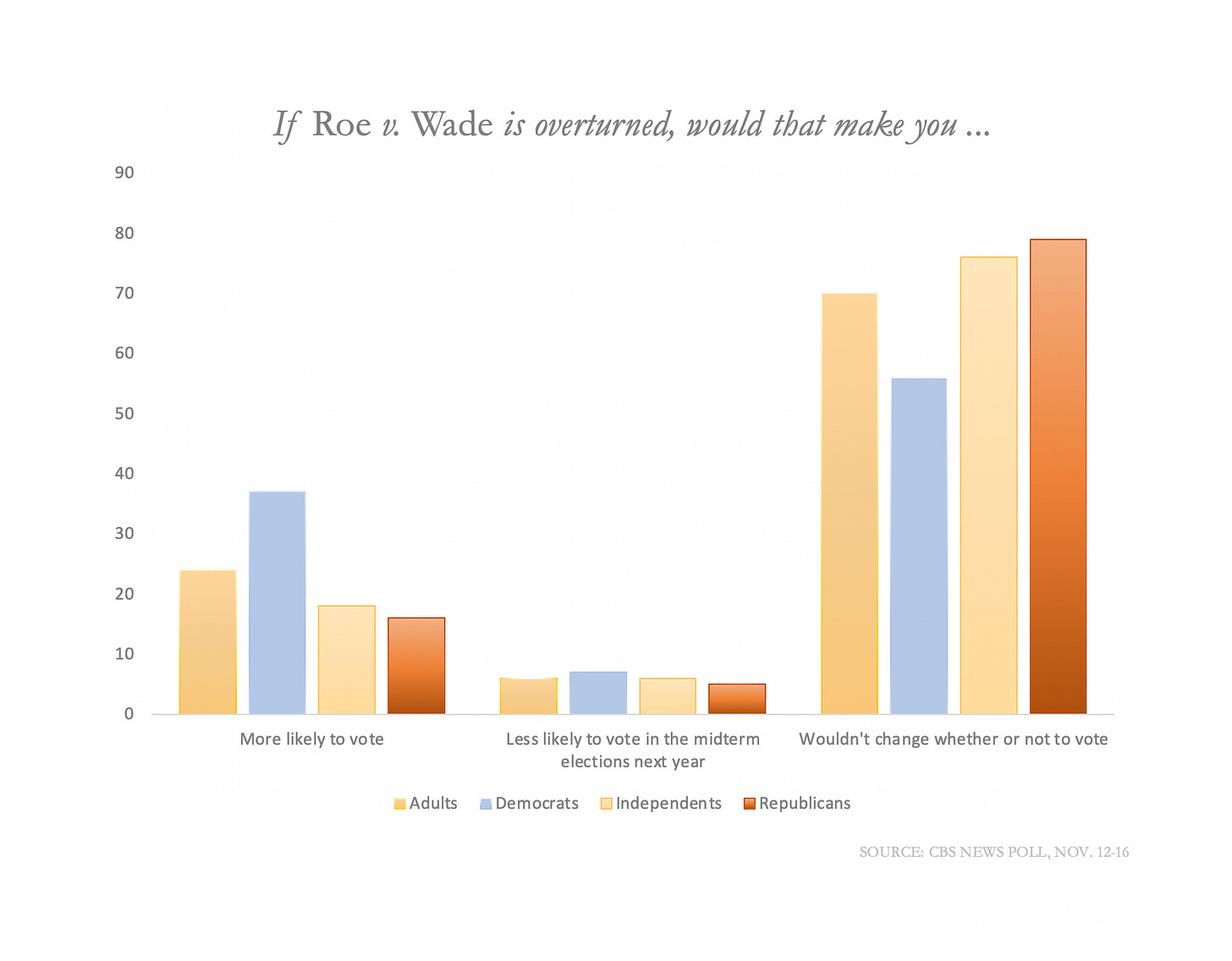

Third, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say that Roe’s collapse would prod them to vote in the midterms. In a CBS News poll taken in November, 37 percent of Democrats, compared to 16 percent of Republicans, said that if Roe were overturned, they’d be more likely to vote in the 2022 midterms. A YouGov poll taken on Tuesday shows another intensity gap: More than half of Democrats in the survey say they’re likely to participate in a protest if the Court overturns Roe. Only 11 percent of Republicans say they’re likely to protest if the Court fails to overturn Roe.

Fourth, the issue seems to help Democrats on the generic ballot. A month ago, when Data For Progress asked voters what they’d do “if the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, and if the election for U.S. Congress in your district was held today,” independents chose “the Democrat” over “the Republican” by 9 points. Overall, the generic Democrat won by 3 points. When the survey described a hypothetical candidate who was “outspoken about defending reproductive rights and protecting access to abortion,” most voters said they’d be much more likely to vote for that candidate. Fewer than a quarter said they’d be much less likely.

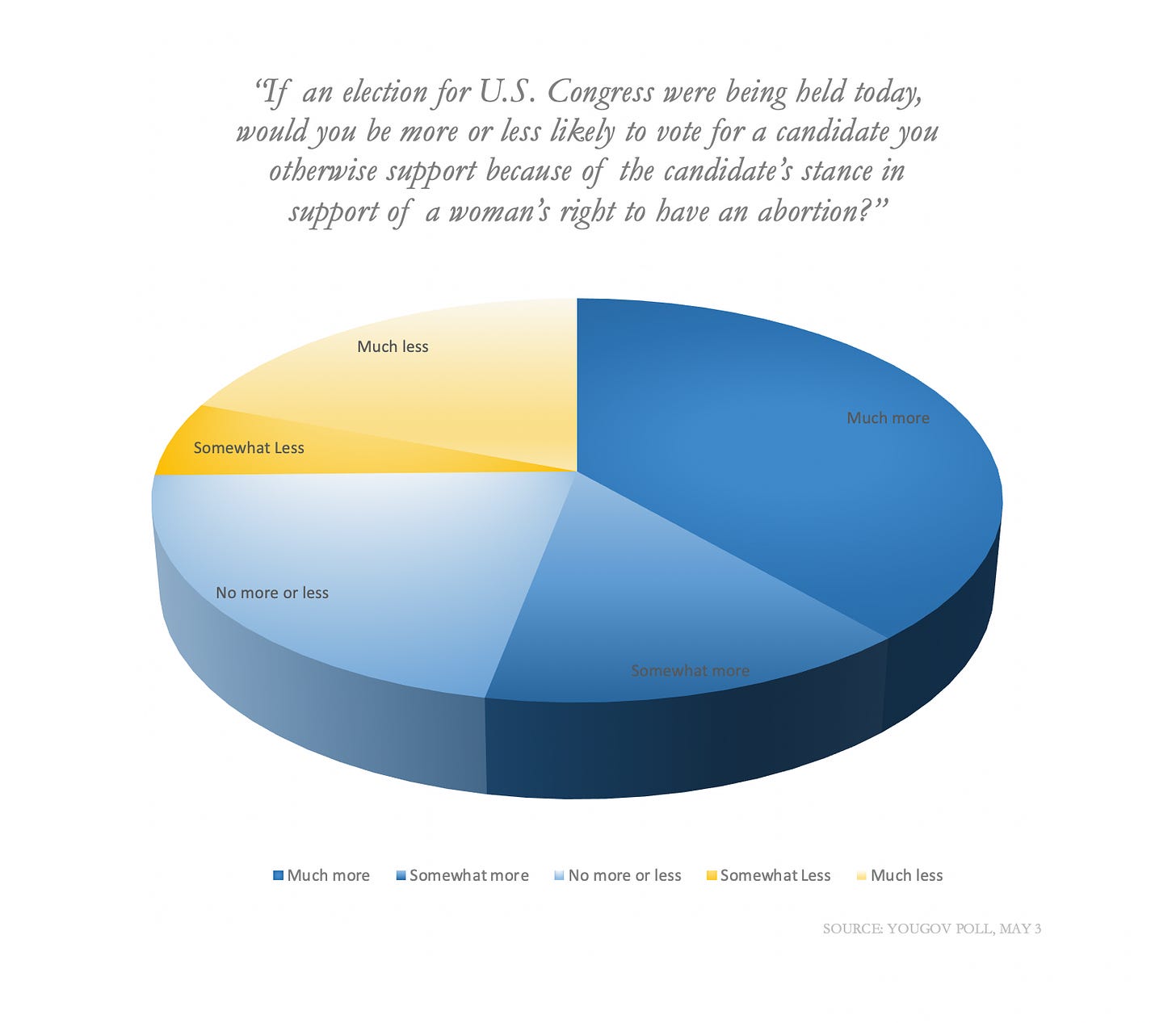

This week’s surveys indicate that since the draft opinion leaked, the pro-choice advantage may have grown. In the new Politico poll, 38 percent of voters say it’s very important to vote this year for a congressional candidate who “supports abortion access.” Only 24 percent say it’s very important to vote for a candidate who “opposes abortion access.” In the new YouGov poll, 44 percent of respondents say they’d be more likely to vote for a candidate “because of the candidate’s stance in support of a woman’s right to have an abortion.” Only 21 percent say they’d be less likely to vote for such a candidate.

Republican politicians could theoretically navigate these currents, but it will be tricky.

The leaked draft opinion alludes to a favorite pro-life argument: that access to adoption and contraception has made abortion unnecessary. But in a December survey by Morning Consult, only a third of respondents bought that argument. Half rejected it.

Another option is to focus on fetal pain. In January, when the Knights of Columbus poll asked whether abortions should be restricted at “the point at which a fetus can live outside the womb” or “the point at which a fetus can feel pain,” more respondents chose the pain standard than the viability standard. But then pro-lifers still have to demonstrate that fetuses can feel pain before viability. And that challenge has proved difficult.

The most effective strategy, recently tested by the GOP-friendly Senate Opportunity Fund, is to position Republicans as defenders of the Mississippi law that’s now before the Supreme Court. If the Court overturns Roe, it will do so to uphold the Mississippi law, which bans abortion at 15 weeks.

The fund’s poll, taken in November, asked likely voters whether they’d be more inclined in this year’s congressional elections to choose a “Democrat candidate who supports unlimited abortion up until the moment of birth” or a “Republican candidate who supports banning abortions after 15 weeks with exceptions for the life and health of the mother.” In the survey, the Republican candidate won, 46 percent to 36 percent.

It’s not clear how many voters will embrace the 15-week position. A ban at 15 weeks does well in some polls, but it fizzles in others. In a Marquette Law School survey taken in January, respondents were closely divided on the idea. In a Washington Post/ABC News poll conducted last week, voters opposed it.

But the alternative position depicted by the Republican poll—”unlimited abortion up until the moment of birth”—is a sure loser. Every survey confirms that most Americans favor a ban on post-viability abortions and that if Democrats alienate pro-choice moderates—people who believe abortion should be legal but who also support restrictions on third-trimester abortions—they’ll lose the upper hand to Republicans.

The Republican poll is a warning: If Democrats don’t accept a prohibition on third-trimester abortions, they could end up losing the right to second-trimester abortions.

If the Court does overturn Roe, the most likely sequence is a series of punts. First the Court punts the issue to lawmakers. Then Congress punts it to the states. Then governors and state legislators punt it to their voters.

The first punt sets up the second. In renouncing Roe, the Court would uphold the Mississippi law. That would allow McConnell and other Republicans in Congress to back out, arguing that states, liberated by the Court, should choose their own abortion laws. McConnell and Rep. Kevin McCarthy, the Republican leader in the House, would try to protect Republican House and Senate candidates in blue and purple states by taking the issue off their plates.

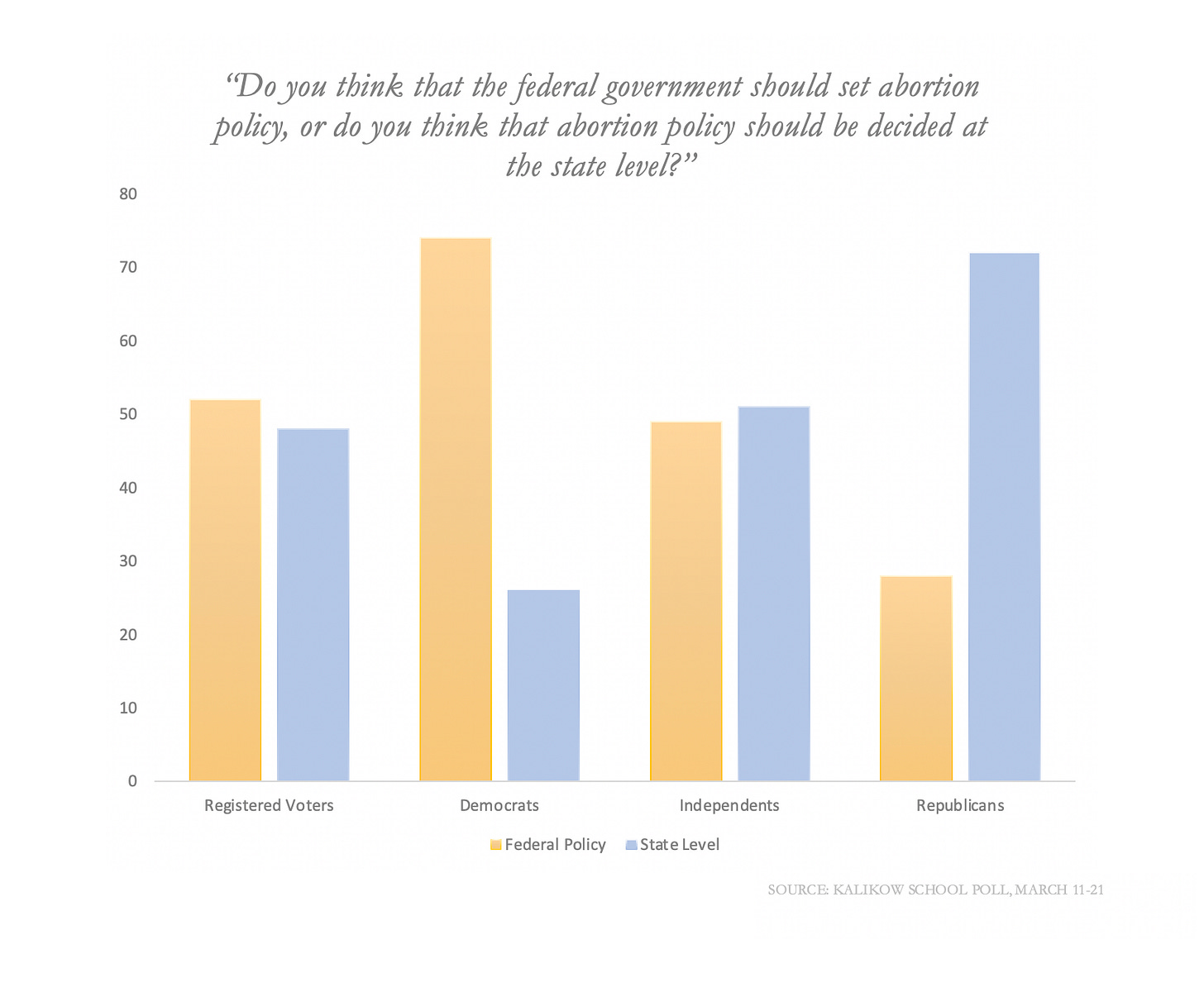

Many Republican voters would protest this cop-out, but most would welcome it. Three recent surveys—one for Reuters, another by Morning Consult, and a third by Hofstra University’s Kalikow School, show that while Democrats want the federal government to decide abortion policy, Republicans want to leave it to the states. Independents are divided, so it’s a wash.

Once the issue goes to the states, Republican governors and state lawmakers face the same problem McConnell is ducking: broad pro-choice sentiment. In February, when a Yahoo News survey asked whether “states should be able to outlaw” abortion or whether it’s “a constitutional right that women in all states should have some access to,” most voters chose the latter. Only about 30 percent chose states’ rights.

That, in turn, leads to the final punt. If pro-life voters want to restrict abortion, and if pro-choice voters don’t want politicians to decide the issue, why not let the two sides fight it out? In the Reuters poll, voters of all persuasions—Republicans, Democrats, and independents—preferred referenda to state legislation as a means of deciding abortion policy. By organizing or encouraging ballot measures, governors and legislators could extract themselves from the issue.

That would be a fitting answer to the court’s withdrawal from the abortion debate. In its draft opinion, the court complains that Roe bypassed democracy, depriving pro-life citizens of the right to “persuade their elected representatives to adopt policies consistent with their views.” The opinion concludes, in a tone of righteous beneficence, that “the authority to regulate abortion must be returned to the people and their elected representatives.”

Don’t expect a thank-you note from the people’s representatives.