The Primary System Is Broken. Here's How to Fix It.

If you want to run for president you should have some skin in the game.

In the months following the 2012 election, Paul Ryan said he found himself in “a bit of a funk.”

“I’m not easily discouraged, but that election was the first I’d lost—and it was a tough one to lose,” Ryan wrote in his 2014 autobiography. Back in Congress, Ryan said he felt he was “going through the motions,” looking for ways to “pick myself up.” (Among those ways was hunting with his daughter, who managed to shoot a 10-point buck.)

The idea of a candidate feeling despondent about losing sounds quaint seven years later. Because for many presidential wannabes today, running a doomed campaign is almost the point. A failed campaign can bring heightened notoriety, vibrant book sales, more cable news appearances, larger speaking fees, enhanced fundraising lists, and a future cabinet position.

And all these benefits come without having to, y’know, actually do any presidenting. Yuck!

If there was once a stigma to losing, it has been washed away in the modern media market, where garnering a small but loyal following is easy to monetize. Out is the Nixon-style bitterness and vituperation; in is social media, publishing deals and Fox News hits. (Or if you’re notable Democratic Georgia non-governor Stacey Abrams, just go about your business as if you secretly won.)

There have been large fields of candidates in the past, but the first modern gaggle of preposterous aspirants bloomed in the 2012 Republican primary. Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich had so much baggage it’s a wonder any airplane carrying him to a campaign destination could achieve liftoff; before Herman Cain had to drop out of the race, he judged the soundness of an economic plan on whether it included the same word three times in succession.

The punishment these ridiculous candidates suffered for stealing voters’ time? Gingrich and former Sen. Rick Santorum can this very day be found as regulars on cable news shows, and Cain was recently touted as a possible appointee to the U.S. Federal Reserve before he removed his name from consideration. Even former candidate/congressional backbencher Michele Bachmann is still in the news: This week she claimed America will never see a president as “godly” as Donald Trump, presumably recalling the time Jesus tried to feed the masses by turning bread into imaginary steaks.

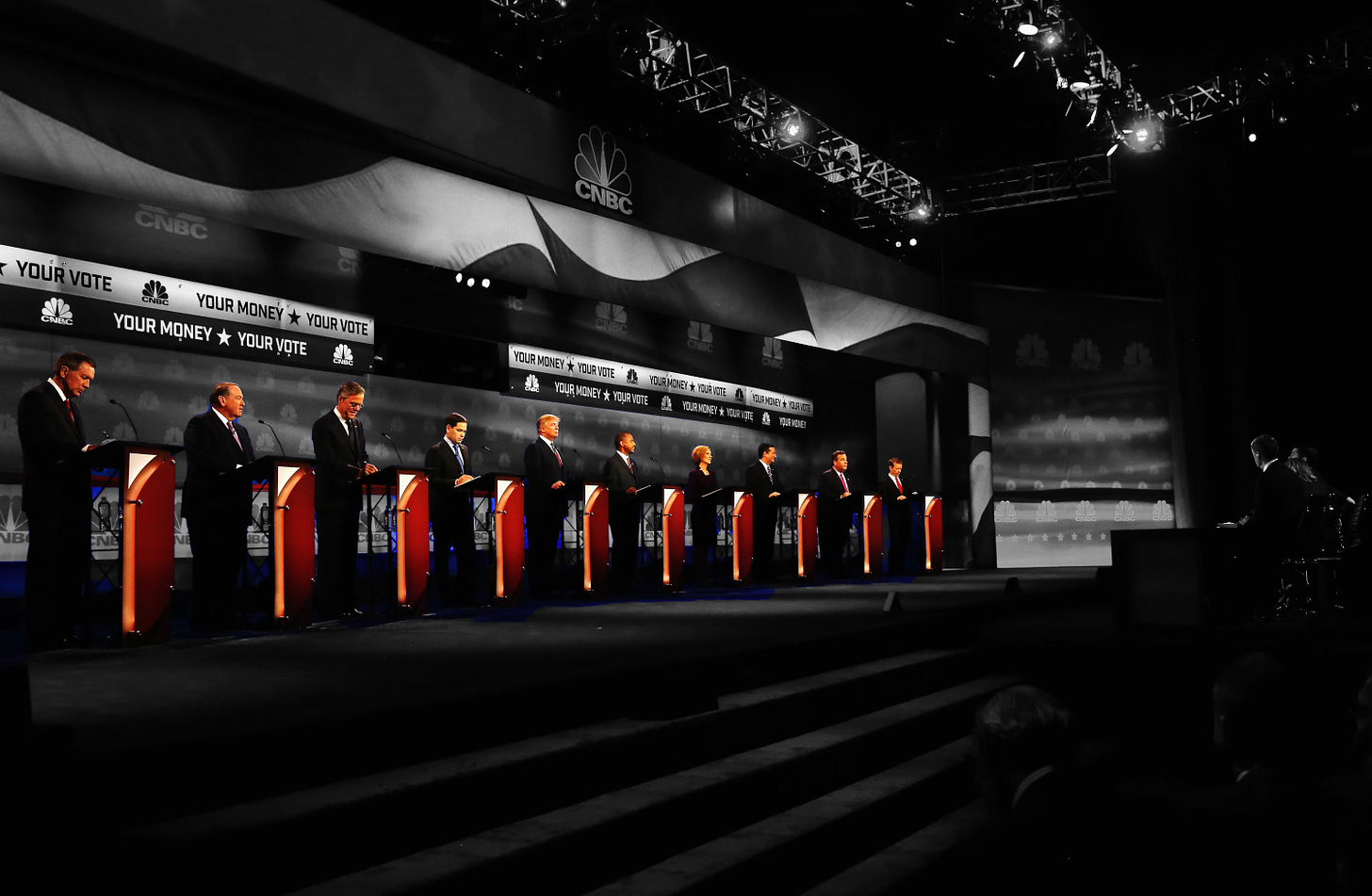

In 2016, the Republican field swelled to an ungodly 17 candidates, foisting names like Ben Carson, John Kasich, and Mike Huckabee (again) on America. (More on this in a bit.)

Now, three years later, the Democratic field is up to 20 candidates and the frontrunner—cranial aroma enthusiast and former Vice President Joe Biden—has just gotten in.

Even candidates best known for losing, like Abrams (who is considering a run) and former Texas Congressman Beto O’Rourke (who is giving us all the charitable gift of his candidacy) seem to think they have enough electoral magic to win the nomination.

Or at least that they have nothing to lose by seeking it.

And as obscure people such as Congressman Eric Swalwell of California, Congressman Seth Moulton of Massachusetts, Congressman Rob Cole of Delaware, and Florida mayor Wayne Messam join the race, they incentivize even more candidates. Because the more widely the field splinters, the greater the chances of being able to win with only a small sliver of the vote. If Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes got in the 2020 race, she might be able to win the nomination simply by collecting the "people who never blink and sound like they're Ferris Bueller’s friend trying to trick Principal Rooney" demographic.

This is a lesson learned by Republicans in 2016: an engorged field can lead to some less-than-stellar ideological results. In the GOP’s case, an unserious candidate was able to win a number of early primary states with a share of the total vote in the mid-30 percent range. Ultimately, Trump won the party’s nomination with 45 percent of the total popular vote, even counting all the states he won by large margins after it was clear he had secured the nomination.

(Also, as evidence the Democratic field has gotten too large, there is no such congressman as the aforementioned Rob Cole of Delaware—he is a fictional U.S. Representative from the film Legally Blonde 2: Red White & Blonde. If your eyes just skipped past the mention of his name, congratulations on being a sane person.)

An important tenet of America’s greatness is that anyone can be president. But as the last three years have shown, a significant flaw of the electoral system is . . . that anyone can be president.

Yet while just about anyone can run, parties have a significant amount of leeway in how they give out their nominations.

Perhaps parties should move to a March Madness-style single elimination tournament to boot the attention-seekers who attach themselves like lampreys to the race. The tournament would run 5 rounds with 10 states participating per round. (The ten states would be geographically diverse and rotate every four years, so as not to have regional bias toward specific candidates.)

In the first week, all the weaklings are weeded out. The first 10 states vote, and the top five vote-getters move on to the next round. Every week from then on, one candidate is eliminated, until the fifth week, which is the final matchup between the top two hopefuls. This would give a truer representation of who a party wants to represent them in November.

Is this a perfect system? Of course not. But the point is that we currently have a problem where running for president is like playing free poker online; without anything at stake, players simply push everything to the middle of the table on every hand knowing if they lose, they just show up the next day and do it all over again. For there to be any order in our elections, losing has to hurt.

Perhaps parties should require their candidates have some skin in the game so they actually feel pain if they lose. They could require each candidate to put up $500,000 of their own money, winner-takes-all. Is it really crazy to think that running a presidential campaign should take as much of a personal investment as opening a Jamba Juice?

The system as we have it is ripe for abuse by people with no capacity for embarrassment who have discovered that they can grift their way to faux respectability. The incentive structure favors fringe candidates with rabid followers who could never compete in a small field of competent professionals.

Consequently, we all must Make Shame Great again, as it seems unlikely we’ll be able to count on President Avenatti to do so.