The Real COVID-19 Death Toll Is Higher Than We Think

The death totals we're seeing are undercounting the full effects of the coronavirus.

1. Uncounted Deaths

One of the themes we've been talking about for the last month is that the official American death toll right now is almost certainly an undercount which will eventually be revised upwards after the epidemic has passed and we have time to sift through the records.

Why? Because most localities seem to be ascribing deaths to COVID-19 only in the presence of a positive test. And since we've had a persistent shortage of tests, many patients in serious condition are admitted without being tested, since they are presumed positive cases and the test can be better used on someone else.

Also we have home-deaths, in which case no testing is performed.

This problem is not unique to America, and has been observed in other poorly-governed countries which were unprepared for the disease, such as Italy.

We're now starting to get a sense of just how big this group of uncounted COVID-19 deaths might be. Let's look at two charts.

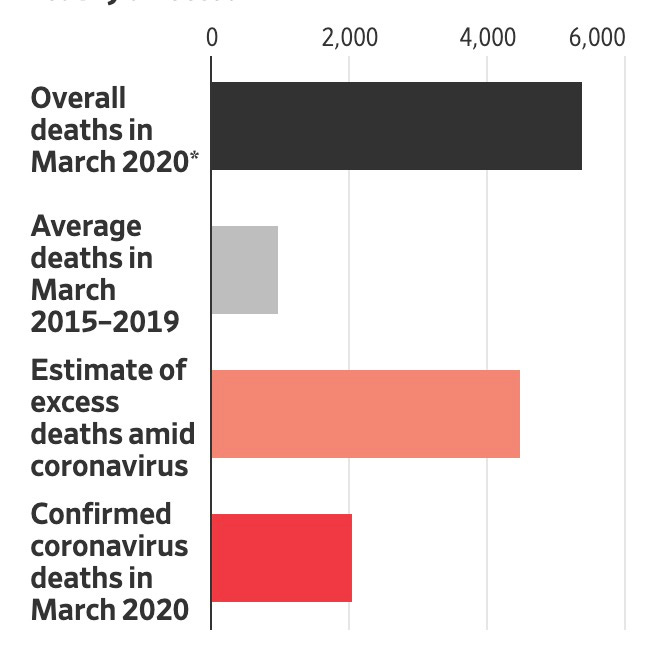

The first is from a Wall Street Journal investigation of the Bergamo province in Italy:

Courtesy of the Wall Street Journal

I've showed you this chart before and I hope it made an impression on you. It certainly made an impression on me, because it shows that the number of uncounted deaths likely attributable to COVID-19 is more than 2x the official count.

That's right: 2,000 official deaths and then almost 3,000 "extra" deaths that shouldn't be there.

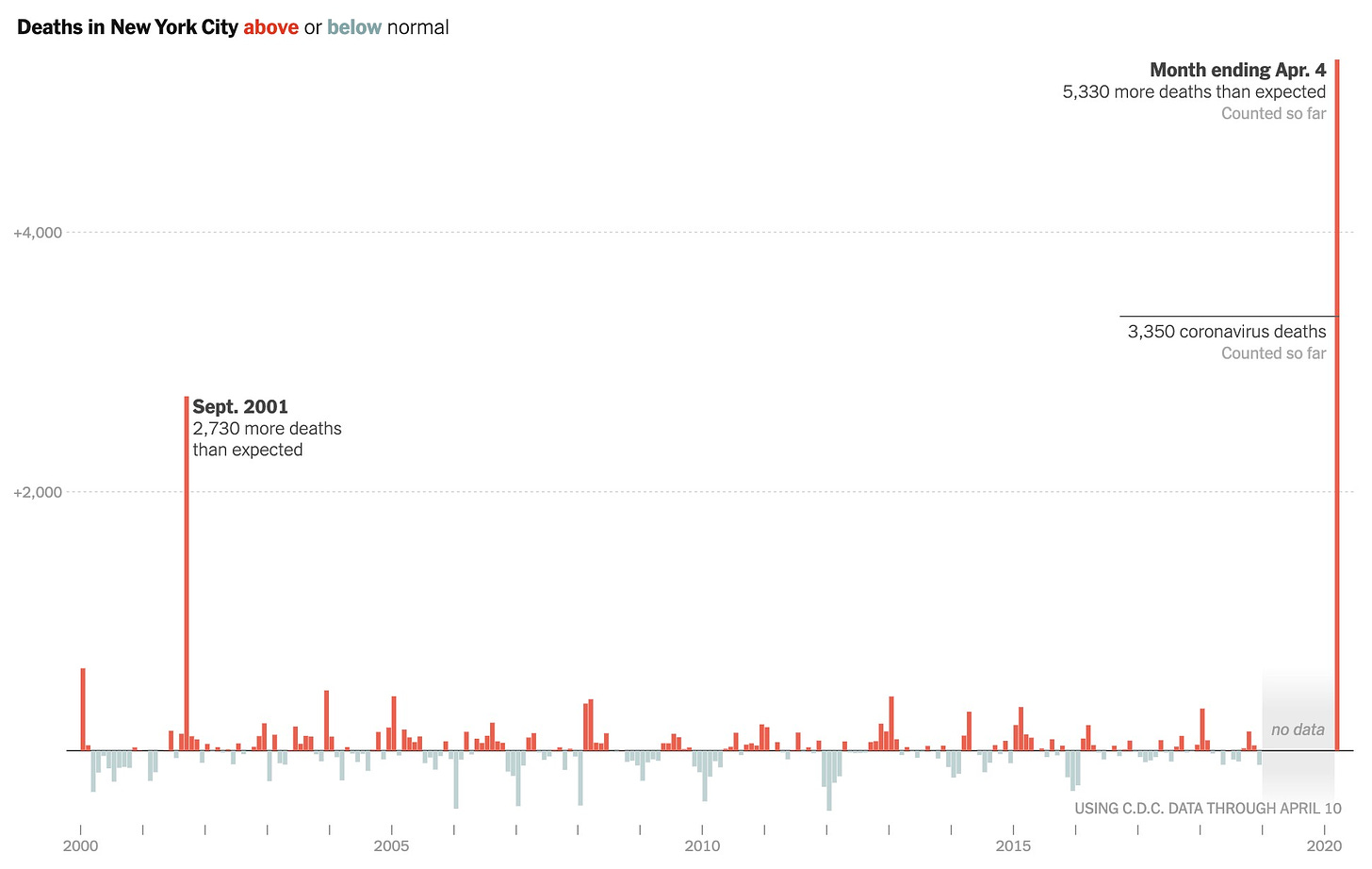

Now, let's look at an investigation the New York Times did over the weekend on deaths in NYC:

Courtesy of the New York Times

So let's do some math together.

Since 2000, the annual monthly variance in deaths has stayed within a very small and relatively stable band: within a few hundred, plus or minus, the monthly average. There's one big outlier, of course, for September 2001.

Now look at the 30-day period ending on April 4, 2020: 5,330 more deaths than the monthly average. And of those, only 3,350 have been officially ascribed to COVID-19.

So what about those other 1,980 dead New Yorkers?

There are a few theoretical possibilities:

(1) As we saw in Bergamo, the official numbers undercount the real COVID-19 toll by a very large percentage: In this case, it's a 60 percent increase over the official number.

(2) A large number of non-COVID-19 deaths occurred among people who suffered other medical events—strokes, overdoses, undiagnosed aggressive cancers—because they could not get access to healthcare because the virus has overwhelmed hospitals.

(3) New York just happened to have the unluckiest month in modern history at the exact same time that a pandemic was ravaging the city.

Like I said, anything is possible. But if I was going to bet $100, I'd put it on (1).

Eventually we will know the answer. Once this is all over, teams of data nerds will comb through all of the death certificates from this period and interview attending physicians and family members and figure out, with a reasonable degree of certainty, what the true number was.

But it'll be bigger than what we're seeing now, even. Possibly by quite a lot.

And as I write this, the official number has gone over 22,000 dead. That's over a span of roughly six weeks.

For a sense of scale:

4,497 Americans have been killed in Iraq over 17 years of fighting.

2,216 Americans have been killed in Afghanistan in 19 years of fighting.

36,516 Americans were killed in the three-year Korean War.

This virus will almost certainly kill more Americans in 20 weeks than all of those conflicts put together.

That's bad enough. But what I keep coming back to is this: Over 20 years of conflict, 58,209 Americans perished in Vietnam.

2. Everything Will Change

Think for a minute about how influential an event the Vietnam war was in American life.

It caused intense social and political disruption. It forced the American military into a defense crouch for a generation. It created constraints on U.S. foreign policy. And all of that happened even when the effects were spread out over two decades.

When you concentrate events, their effects often change, not just in scope, but in kind.

So consider this: In the last four weeks, we have had more Americans killed from this virus than were killed in the single worst year of Vietnam.

And it's not close. We're talking about 20,000 COVID-19 deaths in a month compared with 16,899 Vietnam deaths in 1968.

You may recall that 1968 was a pretty disruptive time in America.

Right now, most of the effects from this pandemic are hidden in shadow because of the lockdown. We are seeing the beginnings—but only the beginnings—of the downstream economic effects. Everything else is going to change, too.

3. Spies Like Us

The great Mara Hvistendahl has a longread on how Chinese intelligence works:

When Candace Claiborne arrived in Beijing in November 2009 to work for the US State Department, her employer was already on edge. The American embassy had just moved from a building at the heart of the city’s diplomatic district to a ten-acre walled compound farther from the centre, a $434m fortress that projected both power and fear. The complex featured shatterproof glass, multiple checkpoints and a moat. To prevent Chinese agents from bugging offices, whole sections of the building had been shipped in from America, a tactic used previously when several floors of the US embassy in Moscow had to be razed following a breach in the 1980s. Even with all the safeguards, it turned out that two American construction workers had passed details about the building to China’s intelligence services. The news rattled policymakers in Washington, DC, who were watching China’s rapid economic and political rise with trepidation. The work environment that Claiborne would inhabit for the next three years included frequent security briefings and warnings about the cunning of China’s intelligence services. “I always tell the men, ‘Go look in the mirror. No beautiful woman, attractive woman, goes up to 50-year-old men,’” said one State Department official.

Though the embassy’s security staff had much to worry about, Claiborne was not an obvious source of concern. A 53-year-old mother of four grown children, Claiborne had the poise and manner of someone used to disciplined work. As a young woman she had dreamed of becoming a ballerina, and worked toward this goal with such dedication that she was admitted to the prestigious Washington School of Ballet. She came from a family committed to service – one brother went into the air force and another into the FBI – but Claiborne decided to follow her dream, and packed up her leotards to move to New York. She had some small victories, but the dance world was cut-throat and sustained success eluded her. After an ill-fated marriage, Claiborne ended up following her siblings into the family business. She became one of the hundreds of unlauded but vital administrators trained by the State Department to keep diplomats’ calendars, prepare agendas for meetings and take notes. Claiborne worked in the part of the embassy that handled classified information, and had top-secret security clearance.

She had lived in Beijing on an earlier tour, following it up with a posting to Shanghai. Normally, the State Department caps employees at two tours in a single country and additional stints require a special waiver. The department’s intelligence officers worry that if a person spends too long in one place, he or she might adopt a casual attitude toward potential security threats. But it was hard to persuade people to go to China, and Claiborne, who didn’t have so much as a parking ticket to her name, passed her security reviews easily. She did have one glaring vulnerability, however, which the State Department apparently overlooked. Read the whole thing. It's so great.