Every week I highlight three newsletters that are worth your time.

If you find value in this project, do two things for me: (1) hit the Like button, and (2) share this with someone.

Most of what we do in Bulwark+ is only for our members, but this email will always be open to everyone.

We’re running a Fall Special right now (not a thing we do very often) and we’ll give you two weeks of Bulwark+ for free, so you can try it out. I think you’ll like it. But if not, no harm, no foul. Cancel anytime.

And you can always sign up just to get on the list for our free stuff, of which there is a lot.

1. Russia

Semi-mobilization—which means something between the draft and a press gang—came to Russia this week. This escalation is a symptom of trouble. It will be a cause of the same.

First, let me point you to Timothy Snyder and his piece on the obscene idea of Russia’s “referendums” on Ukrainian territory:

With Ukraine now on the offensive, Russia announced just a few days ago that it would no longer try to hold “referendums” on the territory it occupies in Ukraine. Then, coinciding with Putin’s speech yesterday, this policy reversed, and now “referendums” are supposedly being held — more or less instantaneously, right now, under conditions of war. People are struggling for a way to speak of this nonsense without using the word “referendum,” which in this context is obviously misleading propaganda, to say the least.

It is best to regard what is happening as a media event. There is not only no legal basis for speaking of a “referendum,” but not even much factual basis for speaking of a “sham referendum.” A sham is shambolic but it does actually exist. What Russia is undertaking is nothing more than a media exercise designed to shape how people think about Russian-occupied Ukraine.

It would be illegal to hold referendums during an armed conflict and under the threat of the use of force. And this is reason enough to ignore the media exercise completely. But it is just the surface of the problem. If held, referendums would indeed be illegal. But we should be careful: even when we say "illegal referendum" we are not quite getting to bottom of things. We might convince ourselves that some voting happened with some flaws.

It takes infrastructure to hold an election. That infrastructure is not there. Although we will no doubt see photographs of old ladies holding pieces of paper, it would be wrong for reporters to speak of a “vote.” What is more: even if the Russians actually had voting infrastructure, which they don't; and even if they intended to have people in the occupied territories vote, which they don't; they couldn't do so, since they do not actually control the totality of any of the regions where they will claim that voting is taking place.

No meaningful voting could be going on, or is going on. The actual situation has nothing to do with Ukrainians or how they might vote. It has to do with Putin’s felt needs. Russia is losing the war, and Putin needs a new wall of illusion.

Read the whole thing and subscribe.

And while we’re thinking about Putin and walls of illusion, here’s Lawrence Freedman thinking through nuclear strategy:

[I]t is not enough to answer the question of whether [Putin] might give a nuclear order by references to his mental state or assumptions that because he is being humiliated he might respond with a tantrum to end all tantrums. We need to consider exactly what problems, military and/or political this might solve. Matthew Kroenig writing for the Atlantic Council warns that a Russian nuclear strike ‘could cause a humanitarian catastrophe, deal a crippling blow to the Ukrainian military, divide the Western alliance, and compel Kyiv to sue for peace.’ But will it? . . .

Take the contributions of Andrei Gurulev, a Lieutenant General, member of the Duma, and regular media commentator, who was directly involved in Russia actions in the Donbas in 2014-15. . . .

He has a thing about destroying Britain. On state television in August, when asked if Britain was readying for war with Russia, Gurulev replied that this was already the case. Russia was fighting both Britain and the US in Ukraine.

‘Let's make it super simple. Two ships, 50 launches of Zircon [missiles]—and there is not a single power station left in the UK. Fifty more Zircons—and the entire port infrastructure is gone. One more—and we forget about the British Isles. A Third World country, destroyed and fallen apart because Scotland and Wales would leave. This would be the end of the British Crown. And they are scared of it.’

More recently Gurulyov noted that Biden had warned Russia against using nuclear weapons in Ukraine. He observed that ‘we may use them but not in Ukraine.’ This time he made particular mention of strikes against decision-making centres in Berlin, threatening Germany with total chaos, along with his familiar theme of turning the British Isles into a ‘martian desert’ in 3 minutes flat.’ He added, oddly, that this could be done with ‘tactical nuclear weapons, not strategic ones,’ and, confidently, that the US would not respond.

Freedman’s point here is that the strategic purpose of Russia’s nuclear weapons has been to keep NATO countries on the sidelines and not directly involved in the war. They continue to serve that function so long as they are sheathed.

Using nuclear weapons would make it more likely that NATO would enter the conflict as a formal antagonist. This is against Putin’s interests.

What about endgame scenarios? Here’s Freedman again:

One can note that Russia is not truly backed into a corner. At the moment there is no existential threat to the Russian state, even if one might be developing to Putin’s personal position, and that the way to get out of any corner is to cross the border back home. And if he wants to escalate he has other options.

Perhaps we may reach such a point eventually:

In the face of such calamity would nuclear use be of any value?

Two possible roles are identified: first, to affect the course of the fighting on the ground, and second, more coercive, to threaten to raise the stakes to terrifying heights, including attacks on cites, persuading the Ukrainians to give up. To a degree this second role is inherent in the first. Once the nuclear threshold has been passed then the barriers to further escalation has been reduced. How might this be done? Options range from a demonstration shot at one end of the spectrum, perhaps against a significant but currently uninhabited site (Snake Island has been mentioned) to make the point that a process has been set in motion with an unpredictable end, to direct strikes against Kyiv at the other end, with battlefield nuclear use in the middle.

The problem with a demonstration is that the message may be unclear. It will show that Russia is ready to ignore the strong normative prohibition on any nuclear use yet is still cautious on making the most of the explosive power.

Read this whole thing, too. And absolutely subscribe. (All of Freedman’s Ukraine posts are free.)

There are scenarios in which Freedman can see nuclear escalation as serving Putin’s interest. But for the time being, these remain lower-probability events.

2. Noah Smith

Looks at AI and asks if it will eventually become Lovecraftian:

Will the kind of intelligence that humans create with AI be an extremely alien intelligence rather than a human-analogous one? Looking at what AIs are doing — both in generative art and in applications like self-driving cars — I wonder if our AIs will be more like the cosmic horror entities in an H.P. Lovecraft story. . . .

First, there’s the interesting question of whether AI is fundamentally incomprehensible. As I see it, this is equivalent to the question of whether AI is actually, literally magic.

At this point you may be thinking of the Arthur C. Clarke quote that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. But this is not what I am talking about at all. A car seems magical to people who have no idea how a car works — but open up the hood and learn about engines, and it becomes clear that a car is mundane. Computer programs can seem magical until you wade through the source code, etc. The “magical”-seeming-ness of most technologies comes from our own ignorance.

There’s a possibility, however, that AI is different. What we call “artificial intelligence” today is basically just a giant statistical regression — an algorithm with a bunch of parameters (hundreds of billions, for recent LLMs) whose values get adjusted when the AI is “trained”. Basically they’re giant correlation machines. As everyone knows, correlation doesn’t equal causation. Which means that when AIs spit out results, we don’t automatically have any idea why they’re getting the results they get.

For this reason, AI is often referred to as a “black box”. We tell it to do something — read written numbers off a page, or predict the next search term you type into Google, or make a robot step over an obstacle, or create a painting based on a prompt, etc. And very often, the AI does what you tell it to do, with a remarkable degree of accuracy and consistency. But unlike a car or a traditional computer program or a spacecraft or a nuclear power plant, you don’t know how the AI did what you wanted.

This is more like the magic spells in a fantasy novel than it is like the hypothetical far-future technologies in a sci-fi novel. Magic spells are incantations that produce powerful results that are (usually) predictable but also ineffable; the wizard knows the prompt to use, and has a good idea of the result they’ll achieve, but the reason that the prompt leads to the result is simply “Well, it’s magic.” In fact, predictable results for fundamentally inexplicable reasons might be a good working definition of true magic.

Read the whole thing. It’s an exceptionally smart discussion of AI.

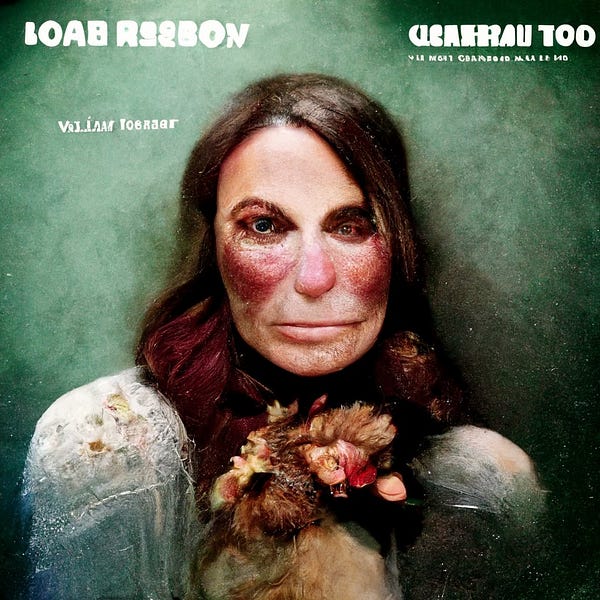

And if you really want to be freaked out, go and read about how AI art generators keep creating a woman called Loab.

I’m not exaggerating. Loab is nightmare fuel.

3. Embedded

We might as well end with something happy: Maybe the era of influencers is coming to an end?

That’s the thesis of this piece by Kate Lindsay:

[F]or what seems to be a growing number of followers, it is no longer so entertaining to watch an influencer perform a life of luxury while you yourself labor at your unglamorous work. In fact, it’s maddening. . . .

The relationship between an influencer and their followers is based in part on a lie: Buy a certain product, and your life can look like mine. But as a creator I recently had coffee with pointed out, the influencer lifestyle is only really attainable by rich people and other full-time influencers.

A prominent home-decor creator’s house, for example, looks the way it does not just because the creator has good taste, but because they have the ability to strike deals with brands and get gifts from publicists—which are then displayed in posts that say, “You, too, can have a house like this if you buy these things.” But a majority of their followers can’t afford to buy all those things. It's unlikely that even the creator, who probably did not buy them, can. The illusion that influencers are modeling authentic, and authentically replicable, lifestyles is vanishing.

Read the whole thing and subscribe.

If you find this newsletter valuable, please hit the like button and share it with a friend. And if you want to get the Newsletter of Newsletters every week, sign up below. It’s free.

But if you’d like to get everything from Bulwark+ and be part of the conversation, too, you can do the paid version.

Subscribed to Freedman, thx for the heads up.

Too anxious to read about Loab. yikes.

And utterly thrilled if today's "influencers" lose their followers. We need completely different influencers now. Decent, Humane, Clever, Natural looking, and HONEST.

Wouldn't that be awesome?

Another good Triad. Thx, JVL.

Will admit up front that I've spent exactly zero-zip-nada time looking at / listening to what 'influencers' do and say. Only know about them from other sources. Probably because I'm of an age that doesn't require the 'modeling' of any 'lifestyle' to influence how I live. All of that happened a long time ago, under the aegis of parents, teachers and contemporaries in the real world, before the digital world gave rise to the phenomenon of these hucksters and their 'followers'.

In our society / economy (it's getting harder and harder to tell the difference between the two) everyone has something to sell, one way or another. The most basic product we have to market is ourselves. We have to sell ourselves to get a job, find a mate, etc. But that we *need* (capitalism always responds to *needs*) influencers to *sell* so many of us a lifestyle is just another indication of the shallowing of our society brought on by the digital age. I'm not complaining about it. What would be the point? I'm just saddened by it. But if this particular phenomenon is beginning to wane a bit, that's a good thing, I think.

However, just as 'the poor will always be with us', so too with Pied Pipers and lemmings. And sadly, there are much more serious consequences from this than a bunch of impressionable dopes trying to mimic a fashionable lifestyle of the moment.

Sigh...