SOME SEVEN WEEKS after the start of a major counteroffensive, Ukrainian forces appear to have breached the first line of Russian defenses near the town of Robotyne. While the full implications—and even the full geographic extent—of Ukraine’s tactical success are still murky, this is good news, not only for the counteroffensive, but for all three of the battles going on in Ukraine right now.

The First Battle: Breaking Through the Surovikin Line

Between October 2022 and January 2023, General Sergey Surovikin was in overall command of the Russian war in Ukraine. (At the moment, he is apparently under some kind of arrest by the Russian Federal Security Service for being a little too chummy with mutineer Yevgeny Prigozhin, who is under no kind of arrest.) Surovikin was, during his brief stint, apparently the most competent commander Putin could have chosen: He orchestrated the organized withdrawal of Russian forces from Kherson, which saved a large number of forces from being surrounded or annihilated by the Ukrainians, and he ordered and oversaw the construction of a web of complex fortifications in the Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine that have been dubbed the “Surovikin line.”

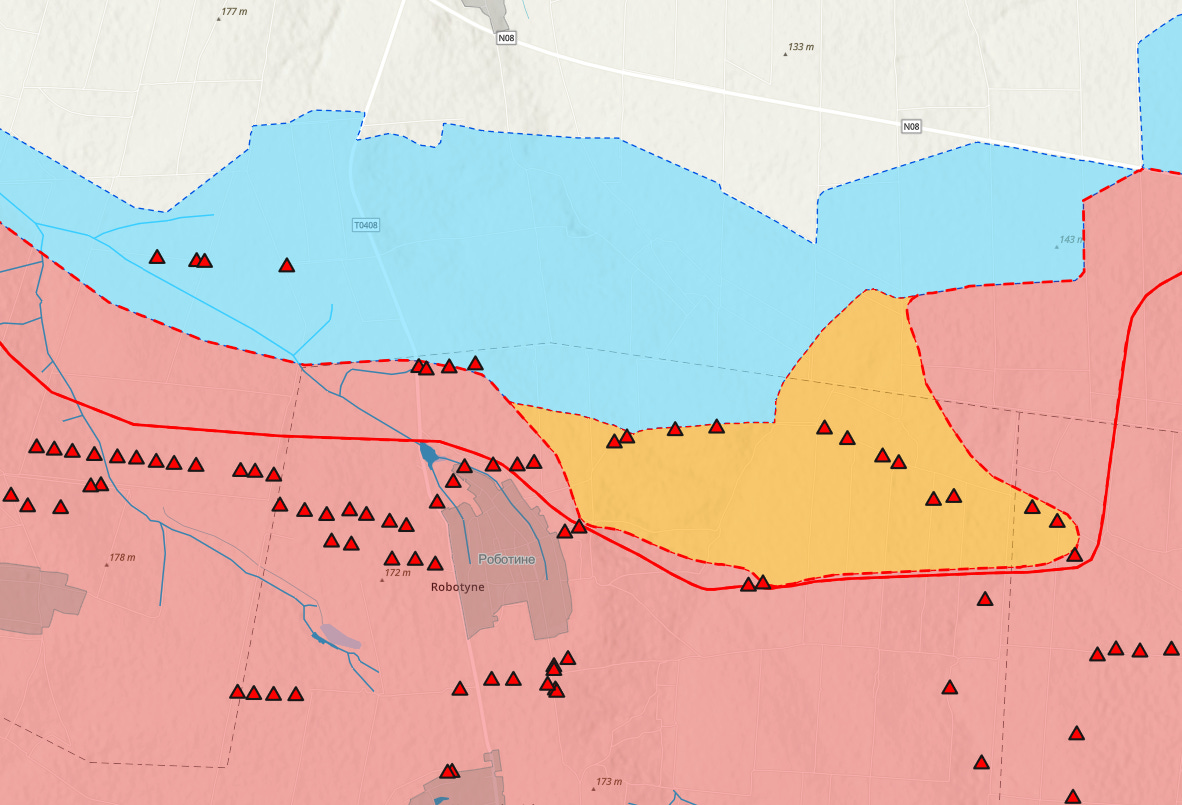

That appellation is a bit of a misnomer, because the “Surovikin line” isn’t really a line, so much as a series of zones, sometimes miles deep, of minefields, tank traps, trenches, booby traps, and other fortifications designed to prevent—or at least complicate—any attempt by the Ukrainians to liberate Russian-occupied territory. The Institute for the Study of War mapped each fortified point they could locate with a little red triangle—it’s not pretty:

Add to this impressive feat of deadly engineering that Surovikin’s replacement, General Valery Gerasimov, is apparently operating a coherent defense, keeping a portion of his force in reserve to reinforce the line wherever the Ukrainians try to break through.

As former Australian Army General Mick Ryan has pointed out, the doctrine most modern armies have developed for breaching defenses like this involves heavy reconnaissance to find the weak spots, massive fire support to suppress the enemy, some way of obscuring the breach itself, securing multiple routes through the obstacles (in case some get closed off), and then the actual assault through to the other side. Even then, such operations are expected to be slow and bloody. Add to that the facts that the Ukrainians lack air cover, and that thanks to the proliferation of drones, there’s basically no way to hide from the enemy, plus, due partially to a lack of mine-clearing vehicles and equipment, the Ukrainians have been doing most of that horrifying and painstaking work by hand. No wonder it’s taken the Ukrainians weeks even to reach the Russian lines.

Yet, at long last, the Ukrainians appear to be on the other side.

It’s possible that things will speed up from here—the subsequent lines of Russian defenses may not be as well-manned as the first line, meaning it might become easier to overcome Russian defenses as the Ukrainians push south toward the sea. It’s also possible that things could slow down, and that, trapped between multiple layers of Russian defenses and surrounded on three sides, the Ukrainian forces outside Robotyne will lose momentum or be repulsed.

Historical comparison: Seven weeks after D-Day in 1944, the Allies controlled most of the Cotentin Peninsula, but momentum had stalled. The hedgerows that Norman farmers had grown for generations to delineate their plots became built-in defenses for the German army—and they covered hundreds of square miles of countryside. Eventually, the Allies were able to cobble together a plan to regain the initiative using three advantages. First, there was superior airpower. Here’s how Rick Atkinson describes it: “Some 1,500 B-17s and B-24s dropped more than 3,000 tons of bombs when COBRA resumed shortly before noon on July 25, with almost another 1,000 tons of bombs and napalm dropped by medium bombers . . . in one of World War II’s most devastating air attacks.” Second, there was obfuscation, and third, huge amounts of armor: The British and Canadians feinted an attack in one direction while the U.S. First Army, with more than 2,000 armored vehicles and hundreds of thousands of troops, attacked in another direction. The Ukrainians don’t have that kind of airpower to muster, nor fresh forces of that size.

The Second Battle: Attrition

In the south of Ukraine, including Robotyne, the battle fits into what is sometimes called sequential warfare. That is, things proceed in order: The Ukrainians are trying to cut the Russian position in half by breaking through to the sea. To do that, they have to break through the Russian defensive lines one after another. The dominoes have to topple in a row.

The story is different in the east of Ukraine, around Bakhmut. This is cumulative warfare. Ever since the Russians decided to make it the centerpiece of their offensive in the fall—which seemed like an arbitrary decision based more on Prigozhin’s desire to prove that, unlike regular soldiers, his Wagner mercenaries didn’t need to rest or regroup—Bakhmut has taken on psychological importance far greater than its geographical importance. The town isn’t a major transportation hub or population center. It only became important because the Russians decided to fight for it.

In a way, Bakhmut is directly connected with another Ukrainian town that’s taken on a new meaning since Russia’s full-scale invasion: Bucha. Because the Russians choose to fight for Bakhmut, the Ukrainians were obligated to defend it, rather than give up its population to the Russian campaign of depredation, deprivation, torture, rape, and murder.

The fight over Bakhmut wasn’t about capturing something; it was about destroying something—namely, the other army. From Putin’s perspective, this made a certain degree of sense: Russia has about 1.2 million men under arms and another 1.5 million in reserves, compared to Ukraine’s 688,000 active and 400,000 reserve personnel. The Russian military could afford to take significant losses—especially when many of them were convicts—as long as Ukraine was also taking losses it couldn’t sustain. For months, observers tried to guess how many casualties each side was taking. The real answer may never be known with specificity.

Since the beginning of the counteroffensive, Ukraine has been counterattacking around Bakhmut, continuing the fight that the Russians chose in the first place. This could be for a variety of reasons: It could be that, since the Wagner mercenaries withdrew and handed the town over to the regular army, the Ukrainians expected to exploit their enemy’s confusion. It could be that the Ukrainians expected the forces around Bakhmut to be tired and low on supplies. It could be that the prospect of recapturing Bakhmut, which the Russian military took months and untold thousands of dead and wounded to secure, in a matter of weeks would be strategic victory for its effects on Ukrainians and Russian morale alone.

Adding to this cumulative strategy is Ukraine’s campaign of attacking Russian logistics, including ammunition depots and the Kerch Bridge.

Historical comparison: The French and Germans first fought over the fortress of Verdun in 1792. The Prussian army defeated the French army in five days of fighting and marched on toward Paris. Fears of invading armies and foreign collaborators led to the September Massacres, in which French troops and guardsmen killed more than a thousand people, most prisoners, suspected of being royalists (and others); the French Republic was proclaimed shortly afterwards, though the Prussians never reached Paris.

About eighty years later, the Prussian Army again attacked Verdun. The Prussians had already defeated the French Army at the Battles of Metz and Sedan, and Verdun was the last major French fortress to surrender.

The most infamous battle of Verdun began on February 21, 1916, and lasted for more than nine months. The German army aimed to force a bloody battle at the fortress and bleed the French dry. Both sides, unwilling to cede ground and betting that the other side’s casualties would be worse, poured men, machines, and supplies into the battle until “there were more than 700,000 victims—305,000 killed and missing and 400,000 wounded (approximately), with almost identical losses on both sides. Yet fighting continued around Verdun until 1918.”

In a sense, the drawn-out Battle of Verdun worked for both sides. By the end of 1918, both the German and French armies were exhausted. Among the factors that ultimately produced an Allied victory were the pressure exerted on the German economy and the massive influx of men and materiel from the United States. Likewise, in Ukraine today, economic pressure on Russia—especially sanctions and export controls that limit the government’s ability to procure high-tech weapons—and American support may decide who wins and who loses.

The Third Battle: Lose the Battles, Win the War

People are bad at many things: conceptualizing large numbers, accepting information that refutes prior beliefs, and predicting how long wars are going to last. Putin thought his “special military operation” in Ukraine would last a few days—maybe a few weeks at most. By now, both sides have accepted the proposition that what decides the war may not be quick decisions on the battlefield, but slow shifts in international politics.

The third battle isn’t taking place in Ukraine, but around the world. Putin has promised to deliver thousands of tons of free grain to several sub-Saharan African countries after withdrawing from the Black Sea Grain Initiative and destroying Ukrainians port infrastructure in Odesa, thereby cutting off those countries from one of their most important suppliers. He’s clearly eager to maintain political cover in the Global South.

Ukraine is reportedly working out defense agreements with the G7 countries, though what those agreements will include remains to be determined. Thanks to massive imports of military technology, the Ukrainian military arguably possesses a technological advantage in some areas over the Russians, but in the long term, international help to develop its domestic defense industrial base will be a better guarantee of its security than shipments of tanks and ammunition.

At some point, the North Atlantic Council and the governments of the 32 NATO members will decide what kind of relationship Ukraine should have with the alliance—possibly including membership, though if Sweden’s experience and the vague, noncommittal language of NATO’s Vilnius communiqué (“We will be in a position to extend an invitation to Ukraine to join the Alliance when Allies agree and conditions are met”) are any indication, that could take a while.

The most important battleground in the war is arguably in the United States. If the Russians are able to prevent a decisive Ukrainians breakthrough until the end of 2024, and if Donald Trump wins the 2024 presidential election, then the Russians stand a pretty good chance of holding on to whatever territory they control. That’s not the victory Putin hoped for in 2022, when he wanted to topple the Ukrainian government and replace it with a puppet within a few days, but it would be a validation of the principle that big countries are allowed to do whatever they want to little countries for whatever reason—and that principle would have been ratified by the American people.

Historical comparison: Five years into the Seven Years’ War (what we in America call the French and Indian War), things were not looking good for the Prussians under Frederick the Great. Squeezed between the Austrians and the Russians, isolated from allies, and starved of supplies, Prussia was almost spent.

Then, something remarkable happened: Russia’s capable, intelligent, shrewd ruler, Elizabeth, died, and her nephew, the Prussophilic Peter III, acceded to the throne. He negotiated an armistice and a peace treaty within six months. Prussia confirmed its status as a great power—ultimately the power that would unite Germany—because a change of leadership led Russia to seek a preemptive peace when victory was at hand.