Real Talk: Can Ukraine Turn Things Around?

A clear-eyed look at where the war stands as U.S. aid begins to flow again after months of delay.

WITH THE LOGJAM FINALLY BROKEN in Congress on funding for Ukraine, what’s next in that country’s fight against Russia’s invasion?

We can dismiss out of hand the verdicts of the social-media pseudo-experts and recyclers of Kremlin talking points—like tech entrepreneur David Sacks, whose reaction to the House vote on the aid bill was to go on a tweeting spree predicting Ukraine’s coming collapse despite the new funding. But some actual experts also warn against expecting too much from the aid package. Russian émigré political scientist Vladimir Pastukhov, a visiting fellow at University College London (and a strong Ukraine supporter), said in an interview that “the format, size, and mechanics of the aid [were] insufficient not only for Ukraine to win a military victory in this war but even for it to offer a steady and lengthy resistance to Russia under current circumstances.” The forthcoming aid, he said was, more “an IV drip” than an effective intervention.

Yet such pessimism gives short shrift to several important factors.

For one, the new aid package does not simply replicate the previous ones but reportedly includes newer variants of long-range missiles that could have a dramatic impact on the course of the war. What’s more, previously promised important deliveries—notably, F-16 fighters, which Ukrainian pilots have been training to use—are finally due to be deployed this summer, provided not only by the United States but by other allies such as Denmark. The European Union, which has boosted its own military and other assistance to Ukraine as a result of the American political deadlock (and has also increased its investments in arms manufacture), will likely continue to come through—among other things, with air defense systems to counter Russian bombings of Ukrainian cities. Right on the heels of the U.S. funding breakthrough, the United Kingdom is announcing its own record assistance package for Ukraine. Ukraine is also in negotiations for more Patriot air defense systems from Europe, even if firm commitments have remained elusive.

Last but not least, Ukraine is stepping up its domestic defense industry, from almost zero before the war. The rise of drone warfare, and Ukraine’s success in using drones to hit long-distance targets from Russian navy ships to oil refineries and defense production factories deep inside Russia, should be a reminder that given the speed of technological development, any prediction about the “mechanics” of this war is apt to be blindsided by reality.

IT IS TRUE THAT UKRAINE will always be outmanned by Russia—that’s just the demographic reality. But when Sen. J.D. Vance declares that this “math” alone spells Ukraine’s defeat, that’s an absurd argument: Taken at face value, it would mean that Ukraine should have surrendered in the first hour of Vladimir Putin’s invasion, when Russia’s manpower advantage was already well known. In fact, Ukrainians have repeatedly demonstrated that they fight better and smarter. Yes, as Vance notes, “Russia has nearly four times the population of Ukraine”—but independent estimates find that Russia’s total casualties have exceeded Ukraine’s nearly 3 to 1, with a staggering 5 to 1 ratio for fatalities (reflecting the fact that Ukrainian wounded have better survival rates).1

No tranche of weapons can give Ukraine an easy path to victory—defined as the expulsion of all Russian troops from Ukrainian territory, or the achievement of a position from which to negotiate a full Russian withdrawal. (And the gratuitous delay in U.S. aid has undoubtedly made this path more difficult.) From the start of Russia’s war in Ukraine in February 2022, reporting on the Ukrainian war effort has whiplashed between pessimistic and optimistic narratives: Ukraine is doomed! No, Ukraine is beating Russia! No, Russia is winning after all! We have now been in a pessimistic phase for the last five or six months, coinciding with the standoff over aid to Ukraine in Congress. But while sober realism is warranted, defeatism is not.

Russia, let’s not forget, faces its own serious battlefield problems. It has made only small, incremental gains since the capture of Avdiivka despite Ukraine’s catastrophic (and about-to-be-remedied) shortages of ammunition. Outmanned and outgunned, Ukraine has still repelled numerous Russian attacks; recent examples of such successful defense include the pushing back and partial destruction of a force of thirty-six tanks and twelve armored personnel carriers northwest of Avdiivka on March 30 and the rout of an armored column near the village of Terny in early April. And U.S.-supplied Ukrainian long-range weapons are still hammering Russian troops even without new deliveries, especially now that the prospect of resumed aid has given the Ukrainian more latitude to use their remaining stocks. ATACMS ballistic missiles may have been used in a strike that heavily damaged a Russian military airfield in Crimea on April 17, a day after a HIMARS strike reportedly took out eight officers at a Russian military headquarters building in occupied Bakhmut.

Russia’s manpower advantage, moreover, comes with staggering morale problems, perhaps best documented by Russian-American journalist Michael Nacke. His analysis of Russian military blogs on Russia’s pro-war “Z-channels” shows them complaining—despite official pressures to avoid negativity—of massive losses covered up by the Russian Army brass. (Convicts, who are now recruited into special army units rather than semi-private mercenary companies such as the infamous Wagner Group, have a particularly low life expectancy: The BBC Russian service has calculated that roughly half are dead in two months—a grisly “prison-to-grave” pipeline, as Nacke puts it.) In a startling twist, one hawkish milblogger recently urged Russian soldiers to kill officers who order them into pointless assaults.

More recently, Nacke has aired new video clips with pleas from Russian soldiers and their relatives indicating that while the Russian military may have gotten better (compared to a year or two ago) at providing its men with food, clothing, weapons, medical aid, and other support, the situation for many remains catastrophic. Desertion is a growing problem; the independent Russian news site Mediazona reports, drawing its data from military courts, that convictions for absence without leave have spiked from roughly 100 a month for most of 2022 to about 600 in February of this year and nearly 700 in March. The abuse of soldiers by superiors, including beatings and extortion, remains endemic; independent Russian media have recently chronicled a harrowing case in which a soldier was beaten to death after a falling out with the unit commander and no arrests were made despite an investigation that identified the killers.

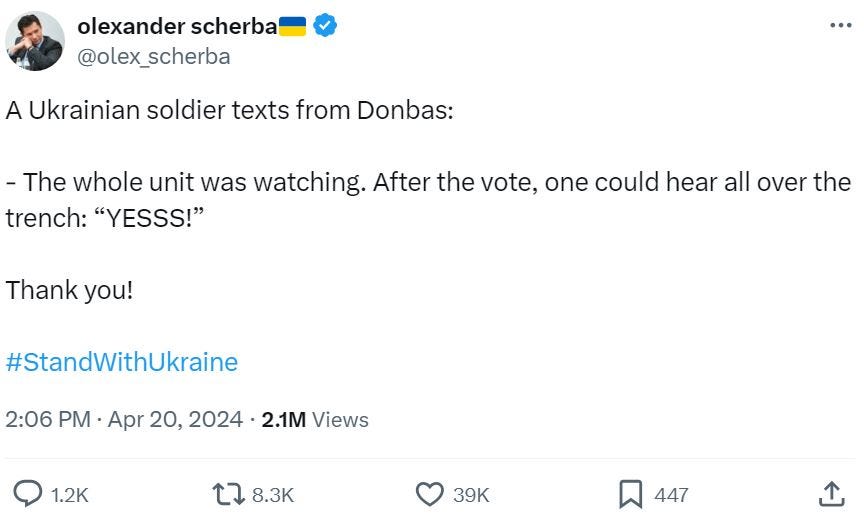

Obviously, Ukraine has its own problems with recruitment and draft evasion; it’s far too early to tell whether the recent law lowering the minimum conscription age from 27 to 25 will have the desired effect in solving the manpower shortage. But the resumption of U.S. support may well improve not only logistics but morale, as this justly viral tweet from Ukrainian diplomat Olexander Scherba suggests:

The idea that Ukraine can’t win even with Western support is not only wrong; it’s a Kremlin propaganda narrative designed to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. As military historian Frederick W. Kagan and Ukrainian-born journalists Nataliya Bugayova and Kateryna Stepanenko argue in a recent article for the Institute for the Study of War, the selling of such narratives in the West is the only strategy by which Russia could win this war.

AMONG THE BIGGEST UNCERTAINTIES that could affect the war is the outcome of this November’s presidential election in the United States. Despite Donald Trump’s seeming recent pivot toward a more Ukraine-friendly position—whether caused by the proximity of the general election or by reluctance to be on the losing side of the congressional standoff—no one who cares about U.S. support for Ukraine should settle into complacency on the subject.

Meanwhile, other shifts in a volatile global situation could favor Ukraine: For instance, Iran’s involvement in a conflict with Israel could negatively affect Iran’s position as a supplier of military hardware to Russia.

One thing is clear: As Russian rhetoric grows more and more unhinged toward both Ukraine (see, for instance, top propagandist Margarita Simonyan’s recent airy suggestion for hangings to bolster discipline in occupied territories) and other countries (see former president and current national security official Dmitry Medvedev’s threats to Poland), the free world needs to live up to its name. And most of its citizens, so far, are prepared for it. “Ukraine fatigue” in the West is another Kremlin narrative meant to be self-fulfilling. In a March Ipsos/Euronews poll conducted in eighteen countries of the European Union, 72 percent of the respondents say that support for Ukraine is important, with half of those saying that it should be “a priority.” Across the Atlantic, a Gallup poll from March shows that 55 percent of American adults want the United States to continue supporting Ukraine in reclaiming its captured territory even if it means “a more prolonged conflict”—down from 66 percent in August 2022, but still a solid majority. So much for claims that Congress defied the will of the people when it voted to unblock the aid to Ukraine.

Perhaps the best commentary on the breakthrough in Congress came from Russian political strategist Stanislav Belkovsky in an interview with former TV journalist and fellow exile Yevgeny Kiselyov. When Kiselyov asked if the House vote was a case of an “unexpected awakening of moral values,” Belkovsky replied:

Yes, of course, because that’s the only foundation for fighting totalitarianism. It became clear that to bury Ukraine or deny support to Israel or Taiwan . . . is to inflict tremendous damage on American global leadership, moral damage above all. . . . Right now, when totalitarianism is in an enthusiastic mood and is stronger than it has been in decades, the decision not to support allies would be destructive, above all to the U.S.-led world order that Vladimir Putin battles. And this affects Democrats and Republicans alike.

Belkovsky concluded that “it’s time to end this gamesmanship in the face of serious global problems.” Amen to that. One can only hope that the damage caused by the long delay, both to American leadership and to Ukrainian war effort, will remain limited and reparable.

While these figures come from a year ago, the casualty ratios are unlikely to have shifted in Russia’s favor; if anything, the opposite may be true, since Russia’s victories at Bakhmut in May 2023 and at Avdiivka in February 2024 came at the staggering cost of so-called “meat assaults” in which thousands of soldiers are thrown into the meat grinder, while Ukraine has reportedly kept its losses in the failed counteroffensive fairly low.