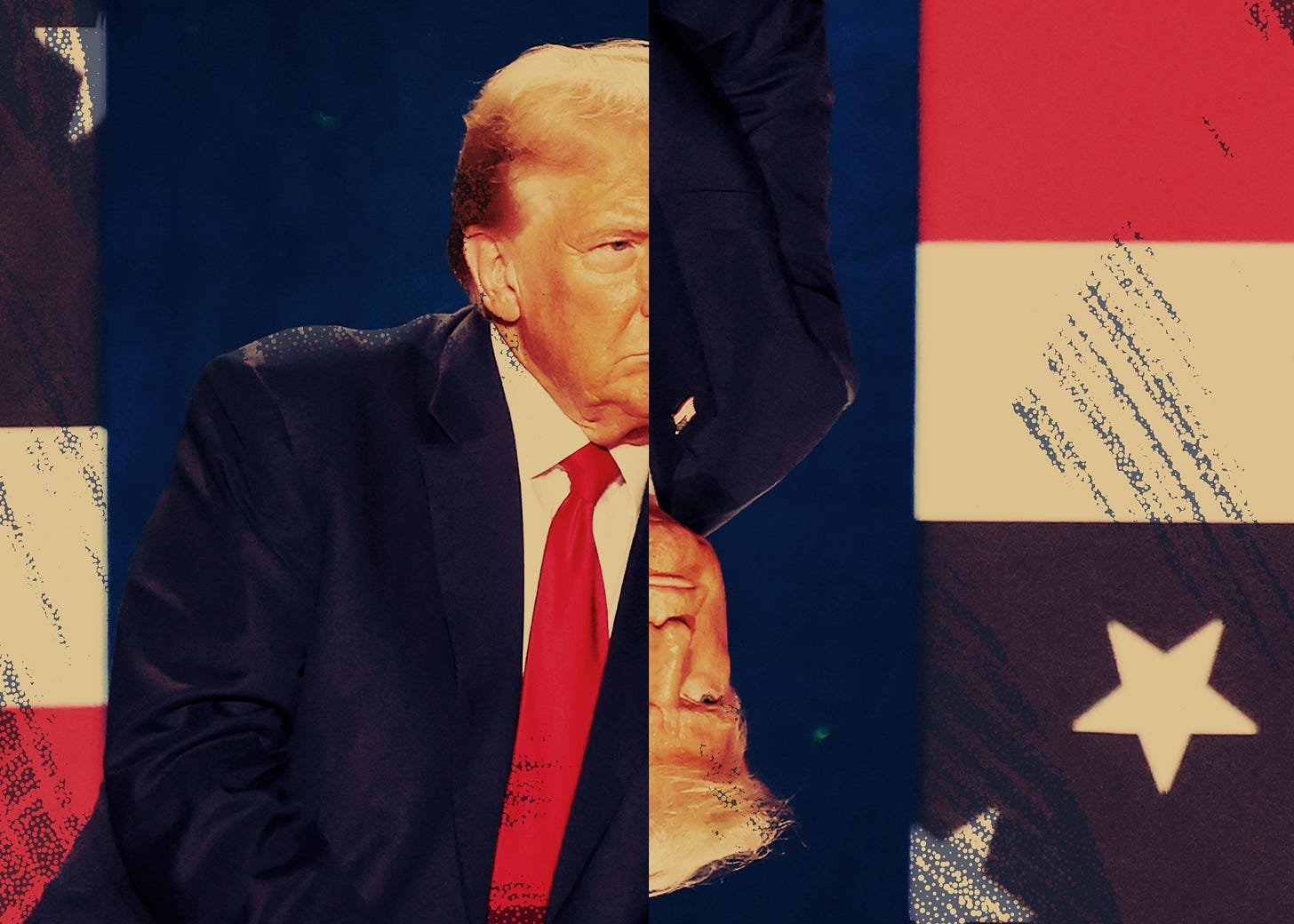

The Upside-Down Election

The Trump-Vance campaign is flouting the unofficial rules of American politics. Will they finally break our democracy, or will those basic standards hold out?

WAS THE 2016 ELECTION A WATERSHED or an outlier? At the time, it seemed like the latter: Donald Trump lost the popular vote by nearly 3 million but squeaked out an Electoral College win when every variable broke his way, including foreign interference. He then led Republicans to three disappointing national elections in a row.

But Trump’s 2016 victory made a lot of political observers go “on tilt,” as poker players call it. A gambler goes on tilt after betting big on a strong favorite and losing, especially when the loss comes to someone playing erratically and getting lucky. It can feel like nothing makes sense, the rules don’t apply anymore, and maybe the best thing to do is the opposite of what you feel you should do.

For eight years, mainstream media institutions have been on tilt in their coverage of Trump: They’ve held him to a lower standard and centered his voters, presuming that nothing can hurt his support and bad things probably help. It is as if the normal rules of politics have been turned upside-down.

The 2024 election will show whether they really have been—and whether Trump’s fluke victory in 2016 really was a watershed.

Trump is running a fascist campaign, the most un-American in U.S. history. Below, I offer eight unofficial rules of American democracy that Trump has broken—rules it would have been unthinkable for an American politician to break before Trump arrived on the scene. If he wins despite doing all that, the system itself will break. But if he loses, and Kamala Harris beats him while standing for pluralist democracy and rule of law, then the old rules will have survived their greatest challenge and proven themselves viable for the next stage of our country’s future.

1. Records Matter

A classic question of presidential politics is “are you better off today than you were four years ago?” The answer for the vast majority of Americans today is an unambiguous yes. It can be hard to remember just how fraught the situation was four years ago: sickness and death, widespread business closures, an economic crash, a spike in violent crime, and civil unrest. But while the incumbent party has overseen significant improvement in all those areas, it doesn’t seem to be helping them much politically.

In 2016, it made sense to treat Trump as an untested possibility because he had never held office before. But now he has a record, and that record is, at best, unimpressive. Trump failed on his main promises—repeal Obamacare and replace it with something better; build a border wall and get Mexico to pay for it—and he is running on the same promises now, as if he was never president. President Joe Biden has even accomplished some things Trump repeatedly promised but never delivered, such as a big infrastructure bill with billions of dollars for the “forgotten” parts of the country the Republican populist supposedly cares about.

Even Trump’s supposed strength, the pre-COVID economy, was mediocre. If we give him a pass on a quarter of his time in office—which no other president gets—and focus on the 2017–2019 economy, it was weaker than the current one.

It’s as though records don’t matter anymore. Maybe it’s all just vibes.

2. Presidential Approval Ratings and Re-election Chances Follow the Economy

The oldest president ever elected saw inflation spike early in his first term, much of it resulting from an external shock. Then it eased in his third and fourth year, after the Fed jacked up interest rates. That president’s name was Ronald Reagan, and he branded the economic improvement “Morning in America” before going on to win re-election in a 49-state landslide. Inflation rose again in Reagan’s final year, but his vice president George H.W. Bush still won the 1988 presidential election easily with an Electoral College margin of 426 to 111.

Inflation under Reagan reached higher highs (10.3 percent compared to Biden’s 8.0 percent), as did interest rates (19.1 percent vs. 5.33 percent). Both were higher in 1984 (4.3 percent inflation, 9.99 percent October federal funds rate) and 1988 (4.1 percent and 8.3 percent) than they are in October 2024 (2.4 percent and 4.83 percent). Unemployment was higher under Reagan, too, reaching 7.4 percent in October 1984 and eventually coming down to 5.4 percent in October 1988. Today, unemployment is at 4.1 percent.

Pick an economic metric—GDP growth, real wages, stock indices—and the United States is currently doing well, outperforming all other developed economies. Some Americans are struggling, but that’s true in every economy, and a higher proportion of Americans was struggling in 1984 and 1988, or in 2012 when Barack Obama won re-election, than are struggling now. But Biden’s approval rating has been net negative since September 2021, and it barely moved as the economy improved.

Maybe material conditions—more specifically, general trends in material conditions in an election year—don’t matter anymore. And maybe the candidate’s plans to improve material conditions don’t matter, either. Sixty-eight percent of Wall Street economists say Trump’s economic plans will create higher inflation than Harris’s, while only 12 percent say Harris’s plans will cause worse inflation. But voters who say they’re concerned about prices don’t seem to care.

3. Crime Doesn’t Pay

This is an easy one: America has never elected a president who is under criminal indictment, let alone one who is a convicted felon. Before this year, no major party had nominated one.

Breaking the law was widely considered, well, bad. That criminality was an electoral liability was obvious: Scroll down Wikipedia’s list of American politicians convicted of crimes and click on a few of their names to see how their careers fared. But a lot of Republican primary voters either cheer Trump’s lawbreaking or shrug it off, managing the cognitive dissonance with absurd conspiracy theories that cast him as a victim. Now the entire law-and-order Republican party, senior officeholders on down, is engaged in a national project to put this one criminal above the law.

There are signs that the Crime is Bad rule still has some of its power. Rep. George Santos (R-N.Y.) and Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) both got indicted, convicted, and pushed out of Congress. New York City Mayor Eric Adams is currently under indictment, and he’s not getting defenses, excuses, or sympathetic conspiracy theories from his party or the press.

If Trump becomes president as a convicted criminal, it will end the rule of law in America. But if he loses, sentencing for his conviction in the hush-money case and the trials for the other cases against him will move forward, and the norm that political leaders should follow the law—even if only because they see lawbreaking as an electoral liability—might return.

4. When Natural Disasters Strike, Americans Work Together

Before Trump, natural disasters were opportunities for parties to put aside politics and work together. These moments reminded everyone that in spite of our country’s political divisions, Americans will always rally to help each other. Bipartisan relief bills in Congress, federal-state cooperation, ex-presidents of both parties doing joint fundraising: They all conveyed the same important message of unity in the face of disaster.

Not Trump. He and JD Vance, along with Elon Musk and the Online Right, have repeatedly lied about the response to Hurricane Helene. Their false claims about FEMA have generated threats and harassment against aid workers, and those claims have continued to hinder rescue efforts despite insistence from local officials that they are false.

As Barack Obama recently asked, “When did that become okay?”

But maybe there aren’t enough people who care. Or perhaps the information environment is so bad that they never hear the truth.

5. While Illegal Immigration Is a Problem, Legal Immigration Is Good for Everyone

Immigration hawks often argued that they opposed illegal immigration, not immigration in general. They’d cite the importance of upholding the law and the unfairness to those who follow the lengthy legal process when many don’t.

The Trump-Vance campaign, and senior aides such as Stephen Miller, have done away with that. In the vice presidential debate, Vance explained that he didn’t care that Haitian immigrants living in Springfield, Ohio had legal status: He was going to call them “illegal” anyway. In office, Trump formed a denaturalization task force to find ways under current law to strip citizenship from more people, and should Trump return to office, Miller promises the initiative will be “turbocharged.”

Going after legal immigrants and naturalized citizens is supposed to turn off voters, roughly one in ten of whom are naturalized citizens, according to Pew. But maybe it doesn’t? Some Americans are into it, and many others either don’t mind or deny what a policy of denaturalization would look like in practice.

6. Overt Racism Alienates Voters

In 1981, Republican strategist Lee Atwater infamously explained that they couldn’t just say the n-word anymore, so his party used euphemisms like “forced bussing” and “states’ rights,” confident their target audience would know what they meant. Ever since George Wallace mounted an independent segregationist presidential campaign in 1968—he won five states in the South, but received less than 14 percent of the popular vote overall—national politicians interested in leveraging racist appeals have done so indirectly, maintaining plausible deniability and relying on what their opponents characterize as “dog whistles.”

The dog whistles have since become bullhorns. Trump-Vance 2024 is an explicitly racist campaign, with Trump channeling Hitler and other twentieth-century fascists by calling his political opponents “vermin,” claiming that immigrants from Latin America are “poisoning the blood” of the country, and by distinguishing between Good Jews (who support him) and Bad Jews (whom he says he’ll blame if he loses). The GOP ticket and their surrogates have not stopped pushing vicious lies to demonize Haitians in Ohio, Venezuelans in Colorado, and minorities around the country. The campaign regularly puts out TV spots that make the infamous 1988 “Willie Horton” ad seem tame, even downright tasteful by comparison.

But the racism doesn’t appear to be hurting the campaign. In fact, Trump is polling better with black and Latino voters—primarily with men—than previous Republican nominees. If the Trump-Vance ticket wins, Trump and Vance will see a mandate to act on their threats of mass violence against “illegal immigrants”—which they say includes legal immigrants, and which would almost certainly lead to attacks on U.S. citizens who look, to racists, like they aren’t from here.

Then again, Republicans running in statewide races who’ve expressed sympathy for Nazis—such as the GOP’s nominee for North Carolina governor, Mark Robinson, who called himself one on an online message board—are lagging in polls, so maybe it’s just Trump.

7. Voters Hold Candidates to Their Promises

Presidential candidates make promises, and their surrogates try to convince voters that the candidates mean them and will actually accomplish those promises if elected. If they fail, some voters will hold it against them. But that’s not how it works with Trump 2024. Swaths of his supporters are insisting he doesn’t mean what he says he will do and won’t actually do it.

A pathetic recent example saw Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin repeatedly insist to CNN’s Jake Tapper that Trump’s threats to use the military against “radical left lunatics” (including, remarkably, Rep. Adam Schiff) was meant to refer only to illegal immigrant criminals, even as Tapper directly quoted Trump explaining that he meant Americans. Some business leaders who know Trump’s proposed tariffs would hurt the U.S. economy insist he won’t do it, even though he imposed tariffs as president and repeatedly vows to impose a whole lot more. Others simply deny anything about him that they find inconvenient.

It looks like they’re rationalizing, telling themselves stories to square the circle of believing “I’d never support a bigoted, anti-democracy criminal” while also advocating the election of a convicted, anti-democracy bigot. But if they’d compromise themselves this deeply for a guy whose viciousness is this blatant, what wouldn’t they do it for?

8. Anti-American Authoritarians Are Bad; Democracy and U.S. Allies Are Good

It’s crazy that the Republican party, which once prided itself on Ronald Reagan’s muscular stance against authoritarians in Moscow, has lined up behind a man who kisses up to Vladimir Putin and advocates abandoning a U.S.-friendly European democracy to Russian military aggression. But here we are.

Previous presidential candidates of both parties disagreed on how America should approach being leader of the free world; Trump is the first to reject the role entirely. He takes Putin’s side, and he gushes with praise for North Korea’s Kim Jong-un and China’s Xi Jinping. He denigrates and threatens America’s democratic allies in Europe and Asia. He, Vance, and various prominent Republicans hold up Viktor Orbán’s Hungary—a picture of democratic backsliding—as a model for the United States to follow.

Trump has shown that a politician can run against a defining feature of the United States since WWII—arguably since the founding, or at least since the Civil War—and remain a viable candidate. If he returns to power despite all that, American democracy and the U.S.-led world order could be damaged beyond repair.

But if he loses, then pro-democracy forces will be invigorated both at home and abroad. As for the Republicans who don’t love the anti-democracy stuff but are going along with it because they think Trump is a path to power and policy outcomes: Self-interest might finally force them to see it as a disqualifying liability.

No modern U.S. election has offered two paths that diverge this sharply from one another. Americans aren’t just picking between policy programs: They’re facing a referendum on living in factual reality, where the basic rules of Constitutional democracy still hold sway. If they choose against it, we might not be coming back.