The Wall Street Journal’s Innocence Project: the Case of Conrad Black

How is “fake news” generated? Or, to put it more precisely, how is “fake opinion” created? The Wall Street Journal’s recent op-ed, “Conrad Black Deserved a Pardon,” makes for an interesting case study.

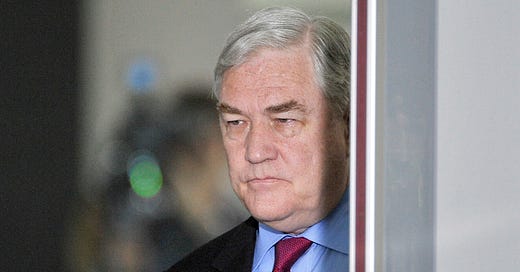

Black, of course, is the newspaper mogul who in 2007 was convicted by a Chicago jury of mail and wire fraud and obstruction of justice and sentenced to 78 months in prison. Released in 2012 after serving 37 months, Black last year authored an embarrassingly fawning book, Donald J. Trump: A President Like No Other. Its oleaginous prose had a predictable lubricating effect on a president whose craving for being buttered up is insatiable. To “expunge the bad rap he had been given,” Trump pardoned Black last week, just as he pardoned previous felonious flatterers like Dinesh D’Souza and Sheriff Joe Arpaio.

To Elliot Kaufman, the piece’s author, Black is not a criminal at all but a conservative hero, “a Canadian William F. Buckley,” who has been victimized by liberals gleefully seeking “a cheap morality tale in Mr. Black’s destruction at the hands of the U.S. justice system.” As for those who slam the president for pardoning a friend, they have difficulty, writes Kaufman, “distinguishing loyalty from corruption.”

Never mind that loyalty and corruption can easily go hand in hand, and putting aside the merits and demerits of the pardon, what does Kaufman have to say about the charges for which Black was convicted? Was Black really the victim of a bad rap or is he, as I see him, an avaricious oligarch who got caught with his hand in the cookie jar?

Black was CEO and effectively the controlling owner of an American public company called Hollinger that, through various subsidiaries, owned newspapers in the United States and abroad. At its peak, Hollinger was the world’s third-largest English-language newspaper company, operating more than 300 newspapers, including its flagships the Chicago Sun-Times, Canada’s National Post, the United Kingdom’s Daily Telegraph and Israel’s Jerusalem Post.

In the late 1990s, the Hollinger chain began to sell off these papers, which is when the various frauds for which Black was convicted began. By 2001, all of the papers were sold except the Mammoth Times, a community weekly for Mammoth Lake, California, which in the year 2000, the year before the fraud, boasted a population of 7,093.

The fraud entailed a payment of $5.5 million from Hollinger to Black and his two co-defendants in exchange for a promise not to compete with this tiny newspaper, owned then by the Hollinger subsidiary APC. These non-compete agreements were drafted, and the payments for them made, at Black’s direction. From beginning to end they were a sham. As a three-judge appeals court panel put it, “that Black and the others would start a newspaper in Mammoth Lake to compete with APC's tiny newspaper there was ridiculous.”

The checks used for the $5.5 million payment had been backdated to the year when Hollinger sold most of its newspapers to make the non-compete provisions appear, as the court put it, “less preposterous.”

Black and his co-defendants failed to disclose the $5.5 million payment to the Securities and Exchange Commission in the mandatory annual 10-K report. Instead, their statement put forward the fiction that the payments were made to “satisfy a closing condition.” In other words, they made misrepresentations in official documents about the diversion of corporate funds.

This is all as damning as it is clear-cut. Black and his co-defendants dipped into the till of a public company for personal gain, cooked up a completely implausible explanation for the money they stole, backdated checks to cover up the fraud, and then lied to the SEC and the public about what they had done. This was not a victimless crime. The victims here, as in all such crimes involving public companies, were Hollinger’s shareholders along with overall public confidence in the integrity of the stock market.

Black and his defenders are quick to point out, of course, that in presenting instructions to the jury, the judge in the case made an error, which eventually, after an appeal to the Supreme Court, led to two of the three fraud charges being sent back to a lower court for review and Black resentenced. But the single fraud charge that was unambiguously upheld operated in precisely the same fashion as the Mammoth Falls scam—the issuance of bogus non-compete agreements—for which Black and his co-defendants were paid.

What does Kaufman say about the counts that were upheld? Remarkably little. All he is able to muster with respect to the various fraud charges is a claim that “Hollinger’s board had variously approved and reported the payments in question.”

In actual fact, the evidence regarding whether the board was in the loop is exceedingly thin. But even if, for the sake of argument, we give Kaufman the benefit of the doubt on his assertion that the transactions were “board-approved,” it would be wholly irrelevant because the non-compete covenants were themselves fictitious. As the appeals court emphasized in its holding: “What makes the contention that the $600,000 was compensation for covenants not to compete additionally and decisively unbelievable is that there are no covenants.” Indeed, the defendants themselves admitted this, a concession that “fatally undermines their challenge to the convictions on this count.”

When Kaufman turns to the obstruction of justice charge, which was upheld on appeal, Kaufman goes into it in a bit more depth. He writes:

Nobody ever looked guiltier of obstruction than Mr. Black, caught on video removing 13 boxes of documents from his Toronto office. Yet he had obstructed nothing. Copies of those documents had already been turned over to the Securities and Exchange Commission—along with 110,000 other pages. Mr. Black had merely been complying with an eviction notice from Hollinger.

This is misleading in the extreme. Kaufman neglects to tell readers of the evidence showing that Black attempted to evade the surveillance cameras, a sure sign of consciousness of guilt. He also fails to note that Black later returned all the boxes to his office, at which point it was impossible for investigators to determine whether the same documents were in them.

This was important because even if it is true that the government already had copies of all of these documents, it was critical to the investigation to determine whether Black had had copies in his office. As the court of appeals explained, “that would mean that he had received them, in which event his denials of knowledge of their contents would be undermined.” The same court declared that the “evidence of obstruction of justice was very strong.” When Kaufman writes that Black “obstructed nothing,” he is purveying a blatant falsehood. A correction is warranted.

Black has packaged himself as a persecuted conservative, steadfastly claiming that he did “absolutely nothing wrong,” a conceit with which Kaufman goes along. But it is important to note that the three-judge panel of federal appeals court judges that first considered and upheld Black’s conviction was not exactly a hotbed of gleeful liberals: it consisted of two appointees of Ronald Reagan and one of George W. Bush. This has not deterred Black from incessantly smearing American criminal justice as “a fascist system” that is “frequently and largely evil,” with the additional ugly amplification that the prosecutors who sent him to prison were “Nazis.”

Proclamations of innocence and attacks on the courts are expected behavior from convicted felons. Black has behaved according to type. Grifters are going to grift, fraudsters are going to defraud, and cons—including pardoned ex-cons—are going to con. But one expects more from the once august Wall Street Journal. Its opinion journalism appears to itself have been corrupted by a perpetual inclination to support Donald Trump whenever it can. It will be a test of the integrity of this Murdoch-owned newspaper to see if readers are given the corrections they are owed.