The Presidential Race Could Use a Third Party—But Not a Third Candidate

The No Labels gambit could create a spoiler in 2024. A better solution for giving moderates a voice: fusion voting.

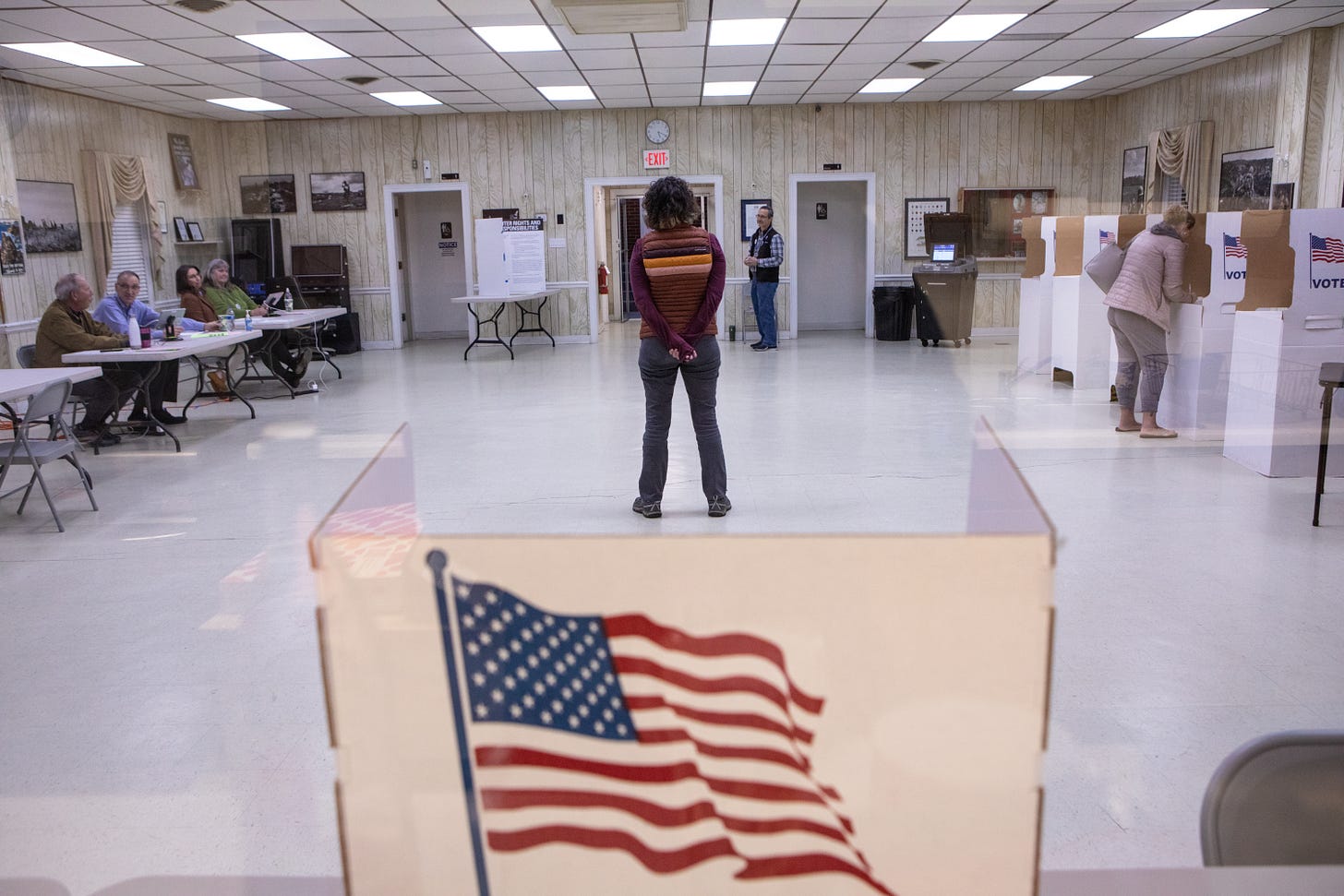

THE GROUP ‘NO LABELS’ HAS RAISED at least $70 million in order to run a centrist, third-party ticket in the 2024 presidential election. They’re right that two parties is too few. But there is a much better way to rebuild the political center and to give Americans more choices at the ballot box: fusion voting, which allows third parties to cross-nominate candidates without spoiling, giving voice and power to the millions who don’t like either the Democratic or Republican parties. And it has a long and rich history in the American political tradition.

The current debate over third-party candidates posits a false choice. The critics of a potential No Labels candidacy are right: a centrist third-party ticket is all but certain to fail and throw the election into chaos. Regardless of which side gains electorally, a spoiled election would be bad for our democracy. In the end, nothing would remain of the quixotic effort but a mailing list of disappointed supporters—an asset that benefits only those who own the list. Still, the answer cannot be that we silence dissenting voices estranged from the two major parties. Americans are frustrated with their lack of choices—and the loss of the political center is a real problem for American democracy.

But looking back into our political history can offer us a path forward. Once legal and practiced widely throughout the country, fusion voting simply means that more than one party can nominate the same candidate on the ballot. With fusion, a centrist party could nominate whichever of the two major candidates was more moderate, incentivizing further moderation and providing a platform for moderate voters to signal why that candidate earned their support. Rather than putting forward a doomed candidate, a centrist party and its supporters could use their leverage to elect the better of two viable options. Crucially, fusion would allow a centrist third party to become a durable and influential part of our politics for years to come. With a political home and identity for the millions of voters stranded between the two major parties, we could have a renewed and powerful political center—precisely what No Labels claims to want.

Fusion voting is a proven way for third parties to elevate priorities, elect winners, and influence policy. In the mid-1800s, third parties committed to abolishing slavery used their nominations to support like-minded major party candidates to advance their cause. Their efforts led to the formation and ascendance of the Republican party, which guided the Union to victory in the Civil War and secured ratification of the Reconstruction Amendments.

Decades later, third parties representing working class voters used fusion voting to secure support for basic labor protections and antitrust regulations from officials in both major parties. In some places, they aligned with Democrats to challenge corporatist Republican rule; elsewhere, they worked with Republicans to oust despotic Jim Crow Democrats.

Because fusion voting allowed third parties to play such an important role, major parties outlawed it in most states at the turn of the twentieth century. Yet, in states where it is still allowed, fusion has remained a pragmatic and effective way for third parties to influence politics. Both Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan won New York’s electoral votes thanks to voters from third parties; JFK would have lost the state and the presidency to Nixon in 1960 but for the votes he received on a third party line. Even today, New York has two influential minor parties, the Working Families and Conservative parties, which primarily cross-nominate and earn hundreds of thousands of votes every election.

A centrist party embracing fusion voting could have extraordinary leverage in the 2024 election. All signs point to another close race, where modest numbers of swing voters in a few purple states could again prove decisive. In exchange for their nomination, the centrist party could secure a commitment from the better candidate to support its key policy objectives, appoint moderate or cross-ideological officials in senior roles, or otherwise prioritize what matters to its supporters.

Is this possible? Absolutely. This strategy is viable now in several states that allow some form of fusion voting in presidential elections. And efforts are underway to re-legalize fusion voting in New Jersey and other states. If No Labels were to invest even a fraction of its $70 million war chest in this direction, they could actually advance their goals of reducing extremism and making our politics more representative. On their current course, No Labels will instead spend a fortune with little to show for it—except putting American democracy in even greater peril.