This Is Not Your Grandfather’s Conservatism

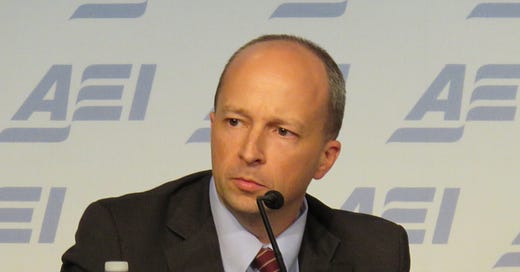

Why AEI’s hiring of Yuval Levin is a good sign for the future of the conservative intellectual community.

The Robert Doar era at the American Enterprise Institute is kicking off with a bang. The think tank announced Friday it has hired Yuval Levin, arguably the most important writer in conservative policy circles in recent years. It is a huge win for the think tank that might also herald broader positive developments in the conservative intellectual community.

Doar, who ascends to AEI’s presidency in July (after being named in January), clearly recognizes that the most important job of an organizational leader relates to talent. Top executives in every industry work overtime to identify, recruit, hire, develop, retain and celebrate the best in the business. But this is doubly important in the world of ideas and triply important in today’s right-of-center intellectual community.

Think tanks—which are valuable only to the extent they accurately assess cultural and political trends, critically analyze policies and proposals, and generate creative solutions—have an outsized dependence on human capital. Moreover, the conservative think-tank community, which largely failed to see 2016 coming and is still struggling to understand its roots and respond to its consequences, would be well-served to see talent development and acquisition as its first-, second- and third-most important jobs.

It’s conspicuous that the Doar era is being launched not with the announcement of a new initiative that he’ll lead or the release of a manifesto of his beliefs, but through a demonstration of servant leadership—casting the spotlight on someone else. This is especially notable because of the peculiarities of talent-management practices in the world of ideas. Academics go through rigorous training related to the literature and methodologies of their fields, but that doesn’t include instruction on how to spot, acquire, and grow talent. Worse, in the academic community, searches are often very narrow—“we need an economics Ph.D. with specialized training in monetary policy of the 1920s”—meaning academics are acculturated to rely on well-established, limited pipelines rather than being schooled on how to develop a talent-acquisition mindset.

Lastly, in the ideas business there can be a high degree and specific type of competitiveness that can thwart talent strategies. In other fields’ organizations, colleagues play different roles in producing a common good or offering a common service. Everyone can succeed. But think-tank types are generally on their own, researching and writing to produce a personal body of work. And there are limited spots in journals, segments on news programs, and column inches to be quoted in articles. The attention of the limited number of consumers of wonkery is a precious resource to be fought over. It’s not a coincidence that folks in these fields seldom praise one another publicly; amplifying another’s luminescence can feel like dulling your own. But by hiring Levin, already a very bright light in the field, Doar is signaling that his organization’s radiance is the sum total of the wattage surrounding him.

Given Doar’s extensive experience as the leader of large organizations--before he joined AEI he was commissioner of New York City’s Human Resources Administration--we should expect other bold personnel moves ahead. It’s worth noting as well that Levin founded and currently edits National Affairs, the pre-eminent conservative policy journal. Through this role, he has helped identify and provide a platform for a bevy of often young, conservative thinkers. Doar’s and Levin’s commitment to finding, grooming, and elevating others bodes well for AEI’s future. But it might also be part of a larger phenomenon. When former National Review editor Reihan Salam was recently announced as the new head of the Manhattan Institute, another prominent conservative think tank, several people noted Salam’s track record during his time as a magazine editor of recruiting and cultivating a wave of promising young writers who later soared.

Perhaps the conservative intellectual community is entering a new era of talent development.

A second reason this hire is notable is that Levin and Doar both have significant governing experience. Though both can research and write, they’ve also served in the policy trenches. The think-tank community can sometimes be an uncomfortable mix of different pedigrees: academics, journalists, advocates, bureaucrats, elected officials, and more. Given their different training, approaches, and habits of mind, these individuals don’t necessarily mesh. The creative tension can be fecund, but getting the right blend isn’t easy. Veer too much in one direction or the other, and the organization’s profile can become too breezy, too tactical, too political, or too technical.

Among the biggest mistakes a think tank can make along these lines is becoming too detached from the day-to-day work of politics and policy. Obviously, it’s important for these organizations to play the long game and engage in big ideas; if they don’t, few others will. But you can lose influence and, more importantly, perspective if your heads are only in the clouds. Studying climate is invaluable, but if you ignore today’s forecast, you can find yourself in the rain without an umbrella. Worse, you can be completely blindsided by a Trump tornado that tears up your town.

The great shame of the modern conservative intellectual community is how badly we missed the coming of, and how ineffectively we have responded to, Trump’s election. Had the think-tank world possessed more on-the-ground governing experience—leaders and staff who’d built careers inside our democratic machine—we might’ve been more attuned to the zeitgeist. Doar, having led major social-service entities at the state and local level, is likely to bring this sensibility to his post and probably hire accordingly. This will help keep the organization rooted in the here and now and enable it to engage successfully with those currently in positions of governing authority. This, too, might be part of a broader theme in the field; the president of the longstanding Heritage Foundation, Kay Coles James, has extensive experience at different levels of government, and its newly hired vice president, Charmaine Yoest, has had multiple governing posts, including most recently in the Trump administration. Eli Lehrer, the co-founder and president of the relatively young think tank for which I work (the R Street Institute), worked for the majority leader of the U.S. Senate.

Public service shapes the servant in important ways. Perhaps in the years ahead, the conservative think-tank world will be increasingly shaped those who’ve served in such capacities.

The final, and possibly most important, reason Levin’s hiring is notable is because of the kind of person he is — and what this portends for the types of people who will be essential in conservative policy circles in the years ahead. Though Levin has intellectual horsepower to burn and stellar credentials (including a University of Chicago Ph.D., time at the White House Domestic Policy Council, etc.), he is kind, gracious, and understated. You won’t find him angling to get on cable talk shows or get invited to give TED talks. He is not even on Twitter! Though he has been engaged in some of the most important and contentious issues of our times, he doesn’t deal in ad hominem attacks, and I’ve never heard anyone describe him as partisan or unfair.

This is especially relevant in this very moment. For the last few days, conservative circles have been riven by the broadside of one writer, Sohrab Ahmari, against another, David French. The issues at the heart of the debate (e.g., the relative importance of cultural issues, the tension between pluralism and social conservatism) absolutely deserve discussion. But Ahmari’s argument was unusually personal and gratuitous and, in places, simply inaccurate, as French clarified. Ahmari’s thrust — that conservatism can’t afford French’s even keel and accommodating politics — was captured by his alarming claim that “civility and decency are secondary values.”

Needless to say, the conservative disposition this is not. But conservatism is also partially premised on the need for modesty and the merits of experience. It never seemed to occur to Ahmari — possessing fewer turns around the sun and a considerably narrower résumé than the target of his ire — that French’s broad experience, including as a soldier and highly successful trial attorney for conservative causes, had produced his even temperament and judicious manner.

Certitude and intemperance are the calling cards and the luxuries of the green. But they also undermine the conservative method of change: respect tradition, appreciate complexity, assume your own and others’ imperfection, protect dissent, practice prudence, reject utopianism, project courtesy, and beta-test incremental reform. In other words, conservative advancements are largely dependent on a conservative process.

The Trump era not only overturned much of the conservative policy orthodoxy, it has also degraded the conservative sensibility. Levin’s new leadership over work on “social, cultural, and constitutional studies” is a powerful statement that the conservative temperament is still indispensable to the conservative cause and that it is essential to the synthesis of the anti-Trump thesis and pro-Trump antithesis of the last several of years.

To be clear, the job of reviving and reforming intellectual conservatism isn’t the stuff of good manners and group therapy; it won’t be accomplished through inside voices and trust falls. The internecine battles have been nasty because they are grounded in fundamental disagreements. Sure, natural humility, a lack of pretension, disinterest in self-promotion and the skills learned through governing experience will be valuable. But the overriding reason the fighting hasn’t been resolved is that neither side has sufficient answers on culture, trade, taxes, infrastructure, entitlements, immigration, or much else.

For the last three years, I’ve been among those standing athwart the Trump train yelling “Stop!” But I’m forced to concede, alas, that much of my party’s base supports the president and that my cause has neither a compelling, comprehensive agenda nor an intrepid leader willing to stand up and sell it.

But it’s also true that extolling Trumpism requires closing your eyes to its incoherence and contradictions. Efforts to encapsulate the president’s governing philosophy mirror the Supreme Court’s fumbling effort in Griswold v. Connecticut to locate in the Constitution a general right to privacy: squinting into penumbras and emanations, hoping to find the outlines of something not there.

Fortunately, Levin has been working for some time to harmonize the dissonance between the pre- and post-2016 eras. Years before Trump descended that escalator, he was helping lead the “reform conservatism” movement which, among other things, sought to find new, middle-class-oriented paths forward on a range of economic and social issues. That group was working preemptively to enable conservatism to bridge political and cultural divides that were still invisible to many. Similarly, Manhattan’s Salam co-wrote with Ross Douthat — a decade ago — the prescient Grand New Party, which aimed at helping Republicans win back working-class voters. Importantly, Salam, Douthat and Levin are only 39, 39 and 42, respectively. This is not your grandfather’s conservatism.

The conservative think-tank community has a good bit of work to do if it is to re-establish itself as a reliable reflection, much less a trusted leader, of thinking and doing on the right. But focusing on talent development, relying on those with governing experience, trusting the conservative disposition, and allowing the next-generation of leaders to take the reins is a very, very good place to start.