Those Were the Days

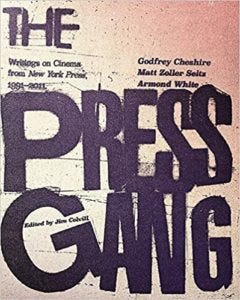

‘The Press Gang,’ a new collection from the NYPress’s trio of film critics, calls to mind a golden age of local newspapers.

While reading the introduction to The Press Gang—a gloriously enormous omnibus of writings by Godfrey Cheshire, Matt Zoller Seitz, and Armond White, the three primary film critics of the New York Press—one is struck by the fact that for a brief shining moment, a free alt-weekly was able to afford having three (3) full-time film critics on staff. [See update below.]

Yes, yes: the criticism in the collection is pretty great too. I’ve only begun to flip through it, having just received my copy from Amazon yesterday afternoon. But even in my cursory examination there are little gems that jump out. Here’s one line in particular that made me smile from the very first piece in the collection—a dual review by Cheshire of My Own Private Idaho and The Rapture: “But assuming that ‘Laurie Parker’ is not a pseudonym for Laura Palmer and that David Lynch didn’t surreptitiously mount both films as a twin peek into the national schizophrenia, we might reasonably link the films’s dissimilar achievements to their makers’ different backgrounds.”

Clever! There's something slightly more profound about his take on Pulp Fiction, which struck Cheshire in part because of the way it offered its characters second chances, paths of redemption.

“The film’s really significant resurrection belongs to film itself, and explains the purposes of Pulp Fiction’s time-shifting structure,” he writes. “More than midway through the story, one of the characters gets blown away. Then in the very last scene, which takes place a few days earlier, he’s there again. Sure, we know logically that, in effect, he’s a dead man. Yet the film’s final shot owes its exhilarating lift to our sudden sense that, no, he’s alive, not just again but eternally: resurrected.”

So yes, the critical writing is wonderful and thought-provoking. But, again, it’s the chaotic spirit of the late NYPress—founded in 1988, shut down in 2011—that impresses, the feeling of puckishness fueled by pre-internet hard-copy ad rates that allowed editor-owner Russ Smith to spend on something as indulgent as three full-time film writers.

“Part of the real magic of the Press in those days was that the office environment was as anarchic and funny and wooly bully as the paper itself,” Jim Knipfel writes in the introduction, fondly remembering nightly excursions to the local bar where “any staffers or freelancers who wanted to join them were free to do so, so long as they were prepared to deal with the free-flowing (if lighthearted) insults that marked the nightly cabal. . . . The office environment was fueled by a lot of alcohol, a lot of drugs, a lot of sex on the ratty office couch, on the desks and behind the elevator, as well as occasional brief explosions of violence.”

It’s hard to imagine such an environment existing today, let alone being celebrated—the exposés would come quickly and generate much tut-tutting on Twitter—but it led to some great writing and great reporting and a film section worth memorializing for its cleverness and combativeness in a large trade paperback a decade after the paper’s demise. And what they were doing in that environment clearly worked: “In May of 1997, the editors announced they were bringing on a third film critic. . . . They were exciting times to be around the office. The paper was still growing, and we’d even forced the Voice to go free in order to compete.”

There’s a whole book to be written about the seeds of decline planted in those words—the “free” model’s reliance on advertisements being the source of so much decline (see also: “Village Voice, fate of”)—but at the time it clearly worked. And The Press Gang is one result.

Any lover of smart writing about film should throw down the $30 this collection costs: the work is largely unavailable on the internet, and poorly formatted when it’s still around. And editor Jim Colvill seems to have done a good job of presenting these three critics in conversation with one another: on the same page we find both the entirety of White’s brief item “Culture’s End,” about the decline of film projection standards, and the beginning of Cheshire’s epic “The Death of Film/The Decay of Cinema,” tackling a similar idea at greater length. Earlier we can find White and Seitz’s reviews of two Malicks back-to-back, White on The Thin Red Line and Seitz on Days of Heaven.

Update: Full-time is perhaps not quite the right way to describe the arrangement, as MZS noted on Twitter:

Still: Three people getting paid a decent amount of money for writing about movies for a free alt-weekly is a reminder of a different, better time.