The Walz Pick and America’s Urban-Rural Divide

Addition not subtraction is the name of the game.

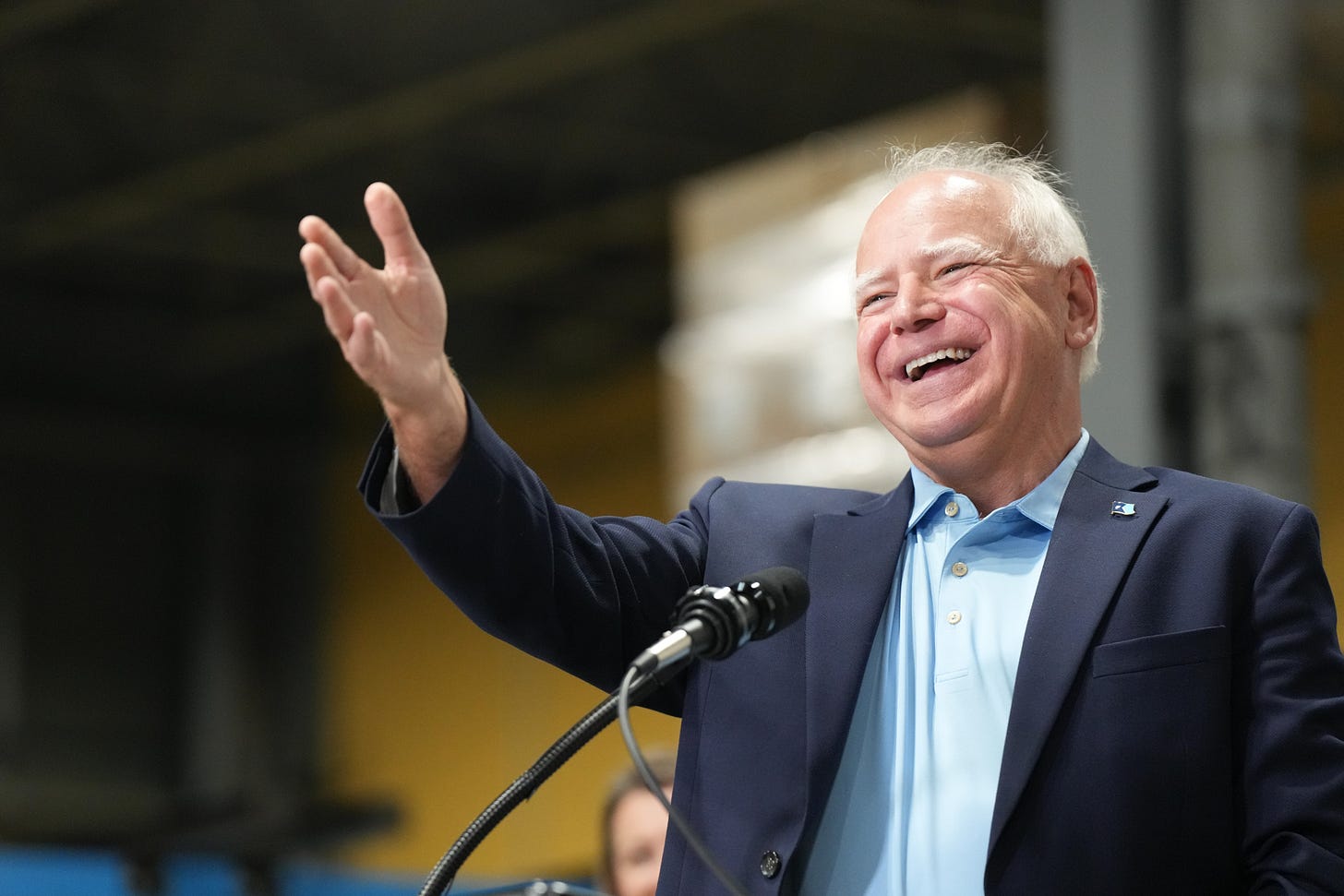

AND THE WINNER of the Democratic veepstakes is . . . Tim Walz, who makes perfect sense. He’s a popular, plainspoken, moderate Midwestern governor, a former teacher, a football coach, a gun owner who hunts pheasant and turkey, and a 24-year National Guard member who flipped a rural Republican congressional district in 2006 and won it six times. Also, here’s a photo of him holding a piglet.

Vice President Kamala Harris chose the second-term Minnesota governor as her running mate for all those reasons and more. What’s really telling is that her two other reported finalists were also popular moderates who made perfect sense: Sen. Mark Kelly of Arizona, a decorated naval aviator and former astronaut with tough border views and bipartisan appeal, and Gov. Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania, known for his working-class outreach, support for school vouchers, and getting a section of I-95 reopened twelve days after it collapsed.

Harris represents an emerging America—a biracial lawyer born to a Jamaican father and Indian mother, both immigrants, both professionals in Northern California. Walz, a Nebraska native, represents “the course-correction on class, rural & regional messaging that Dems have needed for decades,” writes author Sarah Smarsh, a chronicler of working-class rural America who grew up on a Kansas farm.

That balance is the difference between Democrats and today’s MAGA Republicans under Donald Trump, and what could save them this year. They get what the late columnist Mark Shields called a “semi-iron rule” of politics: It’s about addition, not subtraction. Coalitions, not circular firing squads. Finding and welcoming converts—not uncovering and banishing heretics.

None of this is rocket science, it’s basic political science. Ronald Reagan had his Reagan Democrats. George W. Bush, who campaigned on immigration reform, won at least 40 percent of the Hispanic vote in 2004—a GOP record. President Joe Biden had Republicans for Biden, and Vice President Kamala Harris this week launched Republicans for Harris—among them Geoff Duncan, the former lieutenant governor of Georgia, and John Giles, the sitting mayor of Mesa, Arizona.

Even Trump understood the addition imperative in 2016. The reality TV star and novice candidate tapped Indiana Gov. Mike Pence to reassure the traditional and evangelical wings of the GOP. And by gosh, it worked.

This time around, Trump picked Ohio Sen. JD Vance, whose resume includes going after both Trump and “childless cat ladies.” Vance has made amends with cats and Trump, the latter so effusively that he’s now on the ticket as a younger, supercharged, more focused mini-Trump.

A Marine Corps veteran and venture capitalist elected to his first public office less than two years ago, Vance doesn’t bring ideological balance and serves no apparent outreach purpose. He may fire up the MAGA base, but Trump already has a comfortable lead in Ohio and is in little danger of losing other bright red states.

He could use some help in battleground states. But Vance, with his record of judgmental remarks and policy ideas about women, families, and parenting, is not the answer. As I put it last week in a podcast with the New Republic’s Greg Sargent, “You’d think political professionals would be sitting down with JD Vance and saying, ‘We need to add supporters. We don’t need you out alienating people every day.’”

Yet by the end of the week, Trump himself had embarked on a series of one-upping hold-my-beer moments. He insulted over 33 million mixed-race Americans and an audience of black journalists on Wednesday. He continued Saturday when he tore into Georgia’s top Republican leaders—in Atlanta. He also attacked the governor’s wife, with the predictable result that now he’s in trouble with Georgia women.

CONFRONTATION AND EXCLUSION mark the GOP brand in the Trump/MAGA era. The Republican base is hellbent to get its way, while Democrats are generally open to compromise and small gains. Polls show most GOP voters would rather fight and fail than make incremental progress and call it a win.

Nearly two-thirds of Republicans and GOP-leaning independents in a January 2023 Pew Research Center poll—64 percent—said it was important for their party to stand up to Biden, compared with only 34 percent who said their congressional leaders should work with Biden even if that meant accepting concessions. Those numbers were nearly flipped for Democrats and Democratic-leaners, with 41 percent saying Biden should stand up to the GOP while 58 percent said Biden should work with Republicans to get things done.

Most of the Republicans and GOP leaners in that poll were not particularly interested in legislative results. Instead, 56 percent said they were worried their party “will not focus enough on investigating the Biden administration.” I agreed with the 65 percent majority of all U.S. adults worried about the opposite—that Republicans would waste too much time on investigations of the administration—and our concerns were well founded.

At the end of 2023, as the Republican primaries drew near, another Pew poll found that “Trump supporters stand out” for their “dislike of compromise.” While 72 percent of Nikki Haley backers favored “finding common ground with Democrats” even if they had to give up on some goals, 63 percent of Trump voters wanted to “push hard” for what they wanted—even if that made it “much harder” to get things done. I described the attitude this way in 2017: “bipartisanship is for sissies.”

That was overlaid with Trump’s flaky, disruptive approach to negotiating—including but not limited to public ultimatums, social media outbursts, changing positions, imploding infrastructure talks, and derailing a bipartisan immigration reform meeting in the Oval Office by asking for more immigrants from Norway instead of “shithole” nations like Haiti and African countries.

The scorched-earth wing of the GOP is still strong because Trump is still strong. Speaker Kevin McCarthy was forced out of his job because he negotiated with Biden to avoid two separate crises: a debt default that could crash the global finance system, and an expensive, chaotic, punishing shutdown of the U.S. government if Congress did not agree on funding levels to keep it open.

The dramatic clash over a tough bipartisan border security bill put this dynamic in klieg lights, to the particular frustration of Republicans trying to seize an opportunity they did not expect to come around again any time soon. Trump and the party tanked a package that took months of work and had won the backing of the border patrol union.

“It was painful,” Oklahoma Sen. James Lankford, the lead GOP negotiator, told Fox News host Neil Cavuto in April. He said his colleagues “looked for a reason to be able to shoot against it” after Trump said “don’t fix anything during the presidential election, it’s the single biggest issue during the election, don’t resolve this, we’ll resolve it next year.”

He continued:

If we’re pursuing everything, we very often end up with nothing. If we’re pursuing someone coming later to fix it, later seems to never come. When we have a moment to fix things, we should fix as many things as we can then, then come back later and fix the rest.

That remark captures an important truth about how Congress functions, about how Walz functioned when he was there, and more generally about how American politics functions, when it does. The prerequisite for all of this is working across the aisle or even across divisions in your own party, with respect and civility.

President Joe Biden has been that kind of leader, and Kamala Harris demonstrated with her vice presidential finalists and choice that she intends to continue in that tradition. Donald Trump, with his daily barrage of insults and attacks on Democrats, Republicans, and America, reinforces that at 78, he is who he always has been.

Your move, voters.