Tossing Out the Reform Handbook

Revitalizing our parties and rebuilding American democracy from the bottom up.

HOW DO YOU FIX A DEMOCRACY that’s so broken it doesn’t want to be fixed?

That’s sort of what it feels like to work in election reform these days.

On the one hand, the re-election of Donald Trump feels like it must be a blaring wake-up call to the country that our politics isn’t working well at all. For those of us who criticize Trump, his return after so many scandals and crises is a sign of political dysfunction, two-party polarization, and electoral discontent. Across the aisle, many Trump supporters would themselves say they voted for him because of their own concerns about the brokenness of politics and government. Bipartisan majorities believe that our system of government isn’t working and, according to New York Times/Siena polling from a couple of years back, needs either “major reforms” or to be “completely replaced.” The status quo is unpopular for a reason.

On the other hand, 2024 was not a good year for efforts at reform.

In this election cycle, proposed reforms to the structure of elections at the state level—including open primaries, ranked-choice voting, and independent redistricting—lost almost everywhere they were on the ballot. This happened in red states (like Idaho and South Dakota), purple states (like Nevada and Arizona), and blue states (like Colorado and Oregon). In Alaska, the voters very narrowly avoided repealing that state’s four-year-old experiment in ranked-choice voting. Plus, the presidential race—where Donald Trump won the popular vote despite spending significantly less money than his opponent—has muddied the water on two of the most common targets of reform: the Electoral College and money in politics.

So we’re a democracy badly in need of reform, and at some level most people agree about that. But at the same time we’re pretty unhappy about the options for reform that happen to be on the table.

Start by understanding the problem

So let’s throw out the playbook and look at the problem afresh. We see three interlocking political challenges.

First, our politics is wildly devoid of choices. Most elections in most places are not actually elections. Literally. According to a study by BallotReady, 70 percent of all races nationwide in November had only one candidate on the ballot.

This lack of competition adds up. State legislatures in 48 of 50 states are dominated by one party or the other. Only 6 percent of House races were tossups in 2024. Only 9 of 34 Senate seats were really contested. Only one gubernatorial race—in New Hampshire—was competitive. Whether you live in Alabama or California, the people who represent you generally don’t face a lot of competition for their job.

Obviously this is generalizing, but we reckon this collapse of electoral accountability is probably more to blame for declining trust in government at all levels than anything else. How can you trust in a democracy when you don’t really get a say in its leaders?

Second, when we do have choices, we only have two. Because of how we’ve designed our electoral system, we’re locked into two and only two parties. This may not sound like a big deal—after all, it’s the only system most of us have ever known—but the downsides are becoming more clear as a complicated electorate with lots of different racial, class, gender, geographic, and cultural instincts tries to cram itself, uncomfortably, into two parties.

The lack of more parties is also a big part of the reason why most elections aren’t competitive. Republicans in California and Democrats in Alabama may both get shellacked—but a serious, moderate party would probably put up a good fight in both.

Plus there are other downsides to just two options. If you’re a voter who is unwilling to vote for one of the parties—say, because you don’t like its position on taxes—your only practical choice is to vote for the other one, regardless of how flawed that other party’s candidate may be or where the party stands on other issues.

Third, according to political scientists, American political parties are distinctly weak—as in, they’ve become less able to take collective action and act strategically. They’re hollow shells, largely vehicles for individual candidates to advance their interests. The older understanding of our parties as coalitions of people with aligned interests working in concert to advance a policy agenda no longer matches the reality. (Try to put personal biases aside and ask yourself: How coherent is the coalition and agenda the Republican party represents right now? What about the Democratic party?)

The reforms on the ballot in 2024 have their merits, but none of them would have done enough to resolve these three fundamental challenges.

An audacious but simple fix

So if this is the core problem—an uncompetitive, two-party system that’s easily captured by personalistic politicians—how do we fix it?

The place to start isn’t with the White House. Yes, the presidency is vitally important, but it’s just the top of the volcano—or, if you prefer, the end product of the doom loop in our political and party system that extends all the way down. According to political scientists, we could break this cycle from the bottom up.

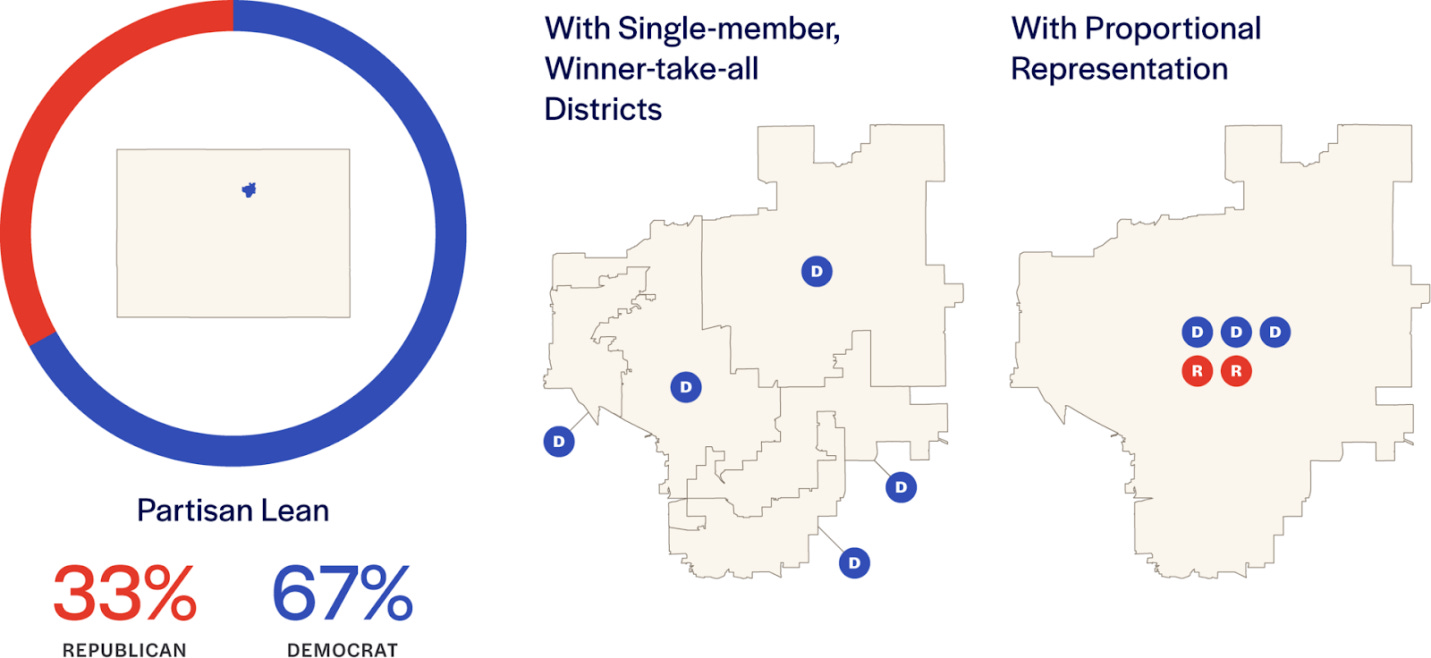

Here’s how. Instead of individual one-seat districts, we could elect groups of representatives from larger regions of states. And elect them proportionally: If 60 percent of voters vote for one party’s candidates, then that party should get 60 percent of the seats, not all of them; conversely if a new party can form and earn 20 percent of the vote, it should get 20 percent of the seats. Instead of allowing candidates to capture party nominations in primary elections, we would allow any serious candidate direct access to the general election ballot, but give parties the right to control which candidates appear on their ballot lines.

Basically, you can think of it as holding the primary and the general election at the same time on the same ballot. You’d be voting both for a party and for the candidate you’d like to represent that party. And instead of redistricting deciding who wins and loses, voters would decide.

Not only would this save money and time, but it would fix the distortions of primaries by allowing all voters to vote on the candidates and the parties on one general election ballot.

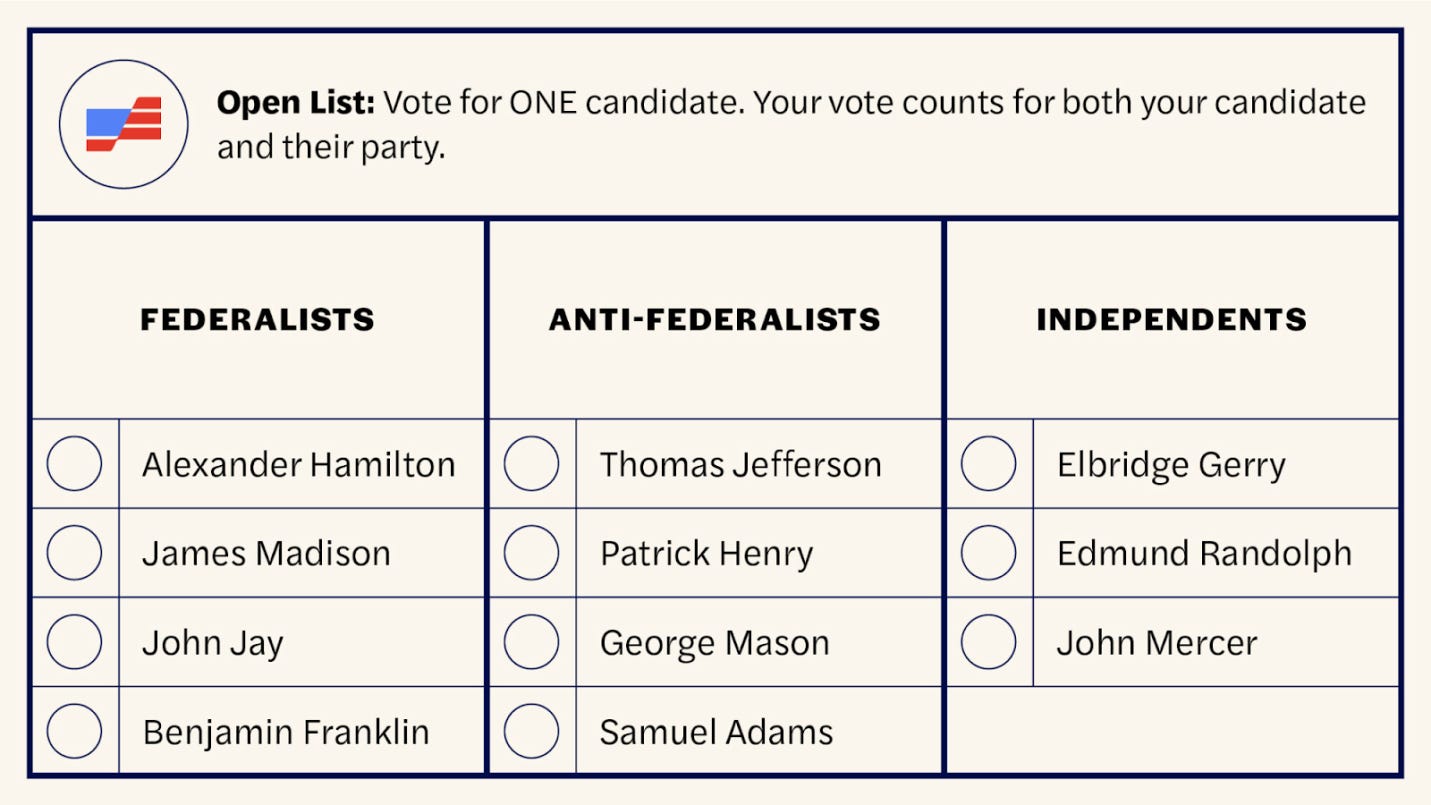

Here’s what such a combined primary and general election ballot could look like:

This idea may strike you as wild, but it’s not. This proposal is called open list proportional representation, and it (along with related list systems) is the most common way of electing a national legislature in modern democracies today, including in countries as diverse as Austria, Japan, Sweden, Indonesia, the Netherlands, Chile, and Ukraine. It has become so widespread because it can achieve the goals of many reformers—competition, better representation for minority groups, no gerrymandering—and it does so in a way that actually builds institutional support with political parties instead of trying to squeeze them out.

A system like that can give us the tools to begin the hard work of building a new kind of politics, resistant to democratic decay and celebrity politics, and dynamically responsive to the interests of the people.

Start in state legislatures, not Congress

One last thing: We can and should start with this reform in the states, transforming our calcified, uncompetitive, single-party legislatures into more dynamic, proportional systems. The states can play an important role in shoring up our democracy against democratic erosion at the federal level. To do that effectively, they need effective institutions.

Here’s what this could look like, taking Colorado’s state House districts 10, 12, 19, 29, and 33 as an example:

And state-level reform can also act as a powerful test case for broader change. About half of U.S. states empower residents to pass laws directly through initiatives. That didn’t happen on its own; the rise of ballot initiatives began around the turn of the last century as Progressives convinced their fellow countrymen that the state of politics was crying out for fundamental reform. November 2026 offers an ideal moment for voters in one or more states to wield that power and introduce a bold and much-needed electoral reform.

This may feel like a dark moment for reform in America. With luck, though, and a lot of hard work, it may prove to be the darkness before the dawn of a renewed, reinvigorated democracy.