Trump Brought African-Style Political Thugs to the U.S.

I spent a career watching African politics. I never expected to see the same dynamics in my hometown.

ONE OF THE GREAT HEARTBREAKS of the Trump era for me is seeing my expertise as an Africa analyst become relevant for understanding political trends in America. For example, when I read Jonathan Rauch’s essay on Trump’s aspiring patrimonialism, a political system in which personalist rule stands in for state institutions, I nodded in recognition of one of the continent’s dominant political features.

As I was waiting for police to respond to a bomb threat at the Principles First conference last month in Washington, D.C.—the source of which is yet to be determined—I thought of yet another growing parallel: What technically would be called “informal security forces” but what I, during my time as a CIA Africa analyst, colloquially called “guys.”

When assessing risks to a country’s political stability or the endurance of a dictator’s power, one of my first questions was always, “Does he have guys?” They can be anything from a hyper-loyal faction of regular security forces to a specially commissioned “presidential guard” recruited from a particular ethnic group to a rag-tag gang of young men armed on the cheap and on the down-low. Most recently, they could include hired mercenaries from Russia or other countries.

Most successful African political leaders in less-than-democratic systems have guys, from current dictators to wannabe dictators. Any dictator worth his salt will cultivate independent armed factions to counter any threats from the military or other potential challengers’ guys. Such groups have the added potential advantage of preserving the reputation of formal security forces in the eyes of the international community. Even popular opposition politicians whose followers are willing to suffer violence—such as Zimbabwe’s Morgan Tsvangirai, whose followers were killed with impunity during the 2008 election—have little chance of achieving power without a security force that can at least wage an insurgency against a dictatorial regime.

Sudan’s former dictator, Omar al-Bashir, created the janjaweed in the early 2000s in an ultimately failed effort to distance his regime from genocide in Darfur (the janjaweed became the Rapid Security Forces, which eventually joined with the military to depose Bashir; now the two forces are waging a brutal civil war against each other).

Across the border, South Sudan is awash in militias formed by various aspirants for President Salva Kiir’s job. Kiir himself has both formal and informal security forces that bolster his regime. Determining which of his opponents has how many armed men is a key component of assessing Kiir’s future.

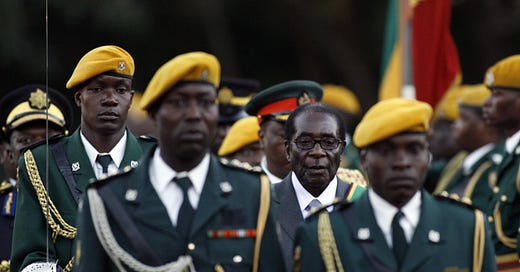

The late dictator of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, had his Presidential Guard but he also had his mob of “war veterans” who terrorized his opposition in exchange for license to forcibly seize whatever farms they wanted. This collapsed the Zimbabwean economy but effectively shored up Mugabe’s regime. He was eventually done in by the regular military, which he mistakenly thought he had on lock.

Politicians in Kenya’s increasingly democratic political scene have long used ethnic gangs to intimidate and interfere with opponents; former President Daniel arap Moi expertly wielded such groups to help him stay in power through the 1990s as the country transitioned to multiparty democracy.

A FEW DEVELOPMENTS IN THE NEW Trump term have me wondering if we’re heading into a new era of “guys” that goes beyond the relentless online attacks on Trump’s opponents. We’ve seen their like in the past in the United States—the urban gangs who helped enforce political machines and the KKK’s reign of terror in the South come to mind—but I can’t think of an example in which such groups acted on behalf of the president himself.

The most obvious blinking red light is Trump’s mass pardon of the January 6th insurrectionists, including members of organized militias such as the Oath Keepers, the Three Percenters, and the Thugs Formerly Known as the Proud Boys (a court recently awarded their name to a black church they vandalized). Fresh out of jail, Enrique Tarrio showed up at the Principles First conference last month to menace former police officers Harry Dunn, Michael Fanone, Aquilino Gonell, and Daniel Hodges, who have been outspoken about their experiences fighting the mob on January 6th and who have been the targets of constant harassment ever since. In his remarks at the conference, Fanone bluntly stated the danger of these criminals’ pardoning as permission to commit more political violence on Trump’s behalf, calling them Trump’s “brownshirts.”

I was similarly horrified by reports that Elon Musk’s private security force now has federal law enforcement authority via the U.S. Marshals Service. While the marshals sometimes contract with private security companies, Musk’s political power, not to mention his egregious conflicts of interest, makes the apparent deputization of his team highly unusual and dangerous. It’s unknown how many officers are now de facto federal agents, but that point seems irrelevant. The larger concern is that he has an established entry point, and he certainly has the financial means, to essentially create an alternative security force that might be used to keep Trump—or himself—in power. How seriously will Elon’s “guys” take whatever oath to the Constitution they may have sworn?

Trump’s and Elon’s “guys” are apparently not limited to just D.C. An Idaho woman was reportedly roughly removed from a town hall meeting by “unidentified” men who appeared to be private security guards deputized by the local sheriff. Subsequent reporting revealed that the men, who did not show badges or wear uniforms, were employees of a company called LEAR Asset Management. The apparently political use of private security companies threatens civil liberties and democratic activity. Sheriffs and police chiefs are responsible to the voters; private security details are not.

The United States’ open gun market adds an element that isn’t present in Africa. In almost all African nations, owning firearms is illegal or strictly regulated and economically prohibitive for most ordinary people, despite a robust black market. Politicians and other monied people are needed to build armed groups, and they usually retain some control over them, although it’s often weak and fleeting. But here in America, it’s easy and within the means of almost everyone to obtain a firearm. Even without direct involvement by political leaders or wealthy sponsors, it’s quite feasible to form a militia and threaten political violence—especially if they can be pardoned or law enforcement can be coopted, ordered, or influenced to look the other way.

In Africa, “guys” are essential for maintaining patrimonial systems, so of course the “guys” benefit as well. Being a militia member is one of the lower rungs on the patrimonial employment ladder. In America, we are unlikely to see “technicals”—pickup trucks jury-rigged to carry machine guns—filled with young men patrolling the streets as they do in places like Somalia or Darfur. We are, for now, still a society of laws and institutions.

What we see may be nothing most of the time, but instead, we may sense an invisible force field of menace that is hard to define, easily denied, but increasingly feared. And that may be enough. Unlike many Africans, who sadly have little to lose, most Americans are entrenched in formal economic, political, and social systems. They have jobs, possessions, reputations, and economic and physical security that they would like to keep. I doubt it will take as many “guys” here to accomplish the authoritarian aims of our new breed of political leaders.