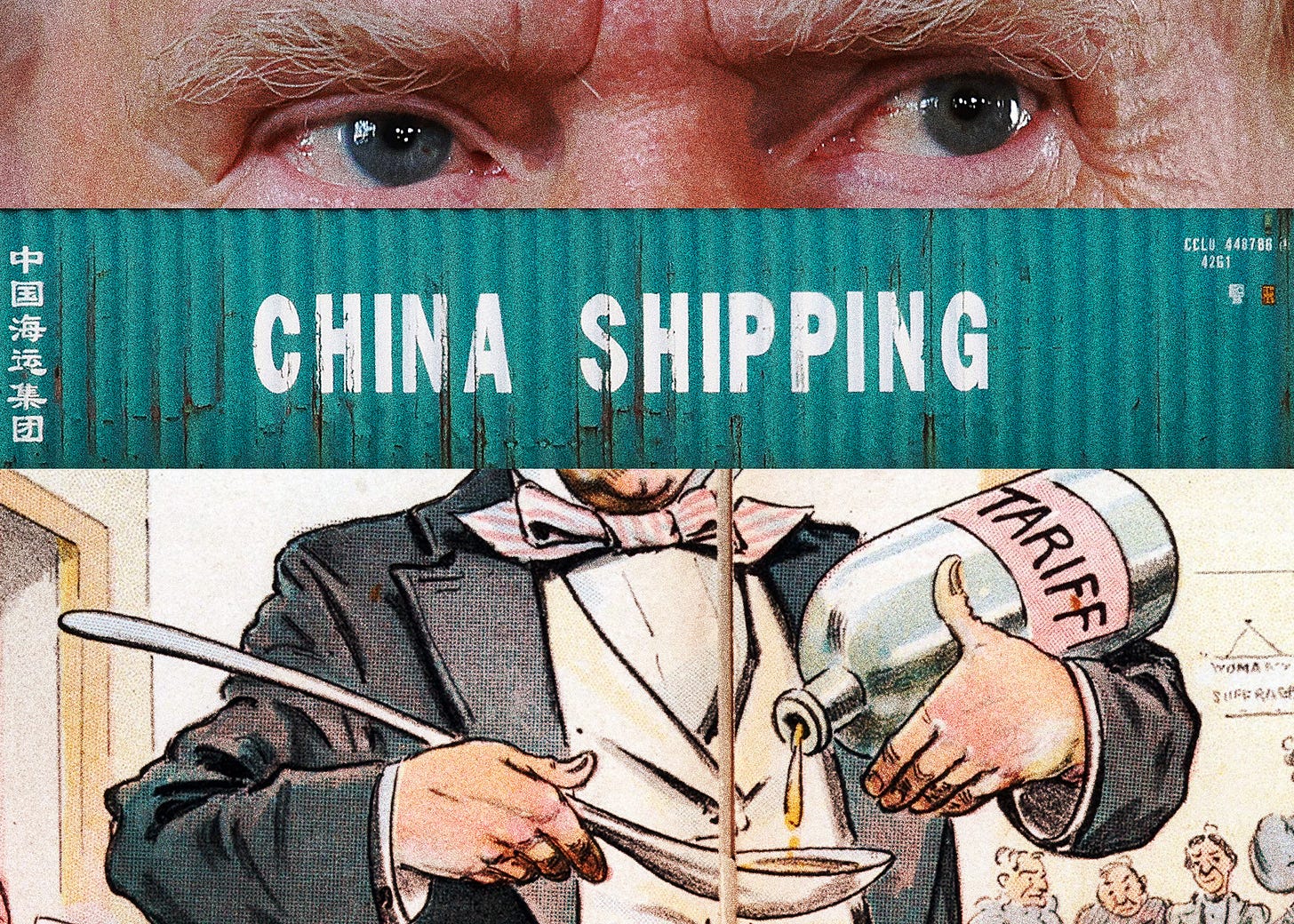

Trump Loves the 1890s But He’s Clueless About Them

The tariffs he keeps babbling about didn’t make that decade great. They helped usher in a depression.

DONALD TRUMP HAS BEEN WAXING nostalgic about the 1890s these past few weeks.

“Our country,” he says of that decade, “was probably . . . the wealthiest it ever was because it was a system of tariffs.”

His love of the era has become so pronounced that it’s now a fixture of his stump speech, meant to defend the massive tariffs now central to the economic platform he’s promising in a second term. There’s just one problem: Trump’s comments are historically oblivious, evincing no awareness of the depression of the 1890s, whose severity was owed, in part, to the protectionist tariffs he praises.

In 1890, William McKinley, a Republican congressman from Ohio, was the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. Federal budget legislation started at his desk, which made him one of the most important people in the U.S. government and in the Republican party. In that latter capacity, he faced a difficult task. In 1884, Grover Cleveland had become the first Democrat elected president since the Civil War. He was defeated in 1888, and the Republicans were now back in control of the White House, the Senate, and the House. They wanted to keep and, if possible, extend their advantage.

The Democrats had regained power in large part by disfranchising black voters in the South and ensuring, through terror and chicanery, a white electorate there. The Republicans in control of the federal government had at first used the U.S. Army in a peacekeeping and administrative role in the South, but when that proved costly—both literally and politically—the Army was ordered out. In 1890, Republican Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge proposed a solution: a law permitting federal supervision of elections upon petition. It would restore black voters’ rights and with them, a Republican majority. Lodge’s bill passed the House but stalled before a filibuster in the Senate.

Republicans therefore looked West for votes. They invented new states from territories with particularly Republican electorates—Idaho, Wyoming, and two Dakotas. But they also had to win the prairie states like Nebraska, full of homesteaders who felt exploited by railroads and banks, and the mining states like Colorado. The Republicans’ traditional policies of subsidizing railroads, banks, and industry were nonstarters with those electorates.

Congressional Republicans in 1890 therefore crafted a solution involving two new laws. One, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, committed the U.S. government to buy—with notes redeemable in gold or silver—4.5 million ounces of silver per month. Farmers thought this program would effectively remonetize silver and cause inflation, thus raising the prices of their crops and making it easier to pay the debts they incurred for mortgages and the purchase of modern farm machinery. Miners, of course, liked the program because it assured them a reliable customer: the U.S. Treasury.

This soft-money sop to the West would be balanced by the other new law, a gift to the traditional Republican constituencies in the East. For as long as there had been Republicans and longer—even during the days of their predecessors, the Whigs—a high tariff had proudly occupied a place in their platforms. In the era before the Sixteenth Amendment, a tariff—a tax on imports—was a major source of federal income. But Republicans wanted tariffs not for revenue, but for protection, as they liked to say: a tariff so high it would render foreign imports undesirable to the consumer. U.S.-based manufacturers could then raise their prices to levels just shy of these tax-induced heights and still appear competitive in the marketplace. Consumers would not buy imports; tariff revenue to the U.S. Treasury would actually fall; the higher prices Americans paid would go into the pockets of American companies.

In theory, these domestic industries would plow their tariff-produced profits into research and development, improving their products and paying higher wages to workers. In practice, this trickle-down theory worked no better in the nineteenth century than it did a century later, and tariffs helped make the owners of U.S. factories into the richest of men.

The tariff law of 1890, called the “McKinley tariff,” levied high taxes even on imports in industries, like iron and steel, in which the United States was already highly competitive. Indeed, the entire economy had been enjoying a four-year boom; there was no evident need for a spur to commerce.1 American enterprise had expanded rapidly into the West, drawing foreign capital—especially, but not exclusively, from British banks—into U.S. securities.

Then came the McKinley tariff. Going into effect in October 1890, it raised the average tariff nearly to 49 percent. It did its job of reducing imports and also reducing income to the Treasury, even as the Sherman Silver Purchase Act increased the Treasury’s payouts.2 The surplus compiled under Cleveland turned swiftly into a deficit under his successor, Benjamin Harrison.

Beyond that, the U.S. government was in the position of buying silver with currency backed by gold, thus steadily reducing the amount of gold it held and increasingly undermining investors’ confidence in the dollar.

Anticipating a crisis, British investors began liquidating U.S. securities. Gold left U.S. coffers. By the start of 1893, U.S. gold reserves fell below $100 million, triggering a general panic of stock-selling and bank withdrawals. Bank runs and failures ensued, followed by commercial and agricultural failures. Double-digit unemployment persisted for years. If we had reliable data on the 1890s, we would understand that depression to have been as severe as the one that followed the Wall Street crash of 1929.

The right thing to do on the heels of the boom on the 1880s and the government surplus might well have been to lower tariffs. But the McKinley Republicans wanted to give something to their Eastern supporters while they were wooing their Western supporters. And, in the way of nineteenth-century Republicans, they thought tariffs were a beautiful thing. They reduced government income, they increased government expenditure, and they undercut foreign investors’ confidence in U.S. reliability, leading to catastrophic effects for ordinary Americans.

Donald Trump’s proposals today would surely do the same.

Trump’s proposed tariffs would occasion another problem: retaliation from trading partners raising their tariffs on U.S. goods. That was a major feature of the nationalist 1920s when, again, Republicans returned to control of Washington after a brief Democratic interlude—this time, the presidency of Woodrow Wilson. In response to the recession that followed World War I, the Warren Harding administration introduced an emergency tariff, as well as emergency immigration restrictions. Both emergency statutes were developed into ongoing policies with the Fordney-McCumber tariff of 1922 and the National Origins Act of 1924. Other countries’ retaliatory tariffs and nationalist policies helped ossify the global economy, all but ensuring that the 1929 panic led to the Great Depression.

In campaigning on his nationalist policies in 1920, Warren Harding not only blathered in a notoriously incomprehensible way familiar to voters now subject to the Trumpian “weave,” he emerged from his fog of bloviation to make promises we might recognize today: “to safeguard America first, to stabilize America first, to prosper America first, to think of America first, to exalt America first, to live for and revere America first.”

Both the politically motivated McKinley tariff and the later protectionist program of the proto–America Firsters led to record-setting depressions. Neither is a policy we should repeat let alone feel nostalgia for.

Eric Rauchway, a distinguished professor of history at the University of California, Davis, is the author of several books, including Murdering McKinley: The Making of Theodore Roosevelt’s America (Hill and Wang / FSG, 2003) and, most recently, Why the New Deal Matters (Yale, 2021).

The exception (there is, in history, always an exception) was the tinplate steel industry, which essentially did not exist in the United States and was subjected to a protective tariff to encourage U.S. steelmakers to manufacture tinplate, thus ensuring a strategic reserve of tin cans; as Douglas Irwin says, the policy “does not pass a cost-benefit test.” The McKinley tariff also removed the tariff on sugar, with profound effects on the kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

More in the way of expenditures went to men who served in the U.S. military during the Civil War under the Dependent Pensions Act of 1890, a belated effort to reward veterans.