JASON ALDEAN’S “TRY THAT IN A SMALL TOWN” is bigger in controversy than charm. It’s not a very good song, nor a very coherent one—but it’s a culture-war hit. The song seems to glorify mob violence in service of a mythical ideal of a small town. With the lyrics’ threatening refrain—“Try that in a small town / See how far you make it down the road / ’Round here, we take care of our own / You cross that line, it won’t take long / For you to find out”—and the music video’s emphasis on flag burning, ACAB, and gun control, it leans into right-wing fears. The original music video, which combined footage of riots with clips of Black Lives Matter protests, seemingly implying they were linked, has been yanked.

Aldean has tried to defend the song from its critics in ways that Mona Charen has rightly described as “fatuous” and “disingenuous.” Still, Aldean’s own views are less interesting and important than the reception the song has received. (Indeed, while Aldean has never been shy about his politics, he didn’t actually write the song’s lyrics.) Once the controversy hit large-scale conservative outlets, streams of the song went from less than 1 million to 11.7 million in less than a week, and the YouTube version of the video went from 350,000 views to 16.6 million. As of this writing, it’s over 23 million.

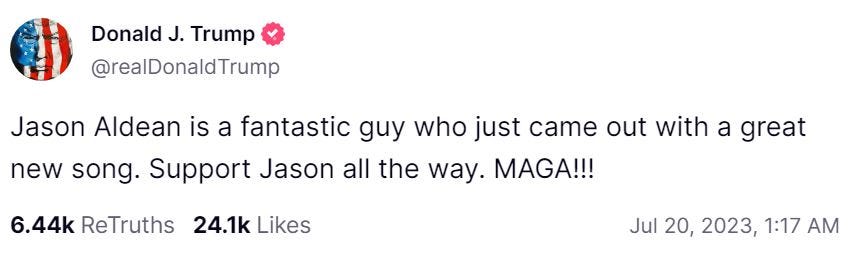

Some of the Republican presidential wannabes have taken to playing Aldean’s song at their events, and as the controversy about the song grew, Donald Trump felt compelled to weigh in:

I was thinking of Aldean’s song as I watched the coverage of Trump’s rally in Erie, Pennsylvania this past weekend, where the rhetoric of mob violence—or even of murder fantasies—was disturbingly on display.

Right Side Broadcasting Network—a pro-Trump internet network that started as a one-man Trump admiration society—was there for the entire Trump event in Erie. And one of the things circulating on Twitter on Saturday was an interview with attendees outside the rally. The interviewer, Matthew Alvarez, talked with a man who said, “I’m here to guarantee Trump gets back in, and get rid of the corruption that’s in the White House right now. It’s a disgrace. He’s a, Joe Biden is a disgrace to this country.” Alvarez replies, “He is a disgrace and so are all the left and the RINOs and the globalists.” And the man says back, “Kill them, every one of them. They can kill them all. Kill them all.” Alvarez responded, “I agree with that” before moving on to the next person in line. Alvarez later retracted his remarks. And perhaps both Alvarez and the interviewee should be given the benefit of the doubt: On live TV, in front of a camera and microphone, people sometimes say stupid things that they don’t mean, things they instantly regret. But it’s an ugly moment.

ONE WAY TO THINK ABOUT THE VIDEO, where at least some of the people in line say they are ready for the murders to start, is as at least partially a performance. So much of what surrounds Trump is performative—the idea that he’s a successful businessman is a TV show, not a reality. The notion that he’s ultramasculine is made for 8kun memes, not reality. The idea that he’s a God-touched avatar of the presidency is a subject of fantasy artwork (or whatever one calls the work of Jon McNaughton). And the rhetoric of violence that suffuses the contemporary far right is at least partially performative in that way.

Trump loves the side glance and the plausible deniability—but the malice that comes with it is clear. Representative Mike Kelly took to the stage during the Erie rally to pose challenge questions to the crowd:

How much do you hate losing? How hard is it, that you will go to any extreme to keep from losing? What length will we go to? What price will we pay? What role will we play? You’ve got to hate losing with everything in your body. And if you do that, the byproduct of that is that you’re going to win. You’re going to win.

It’s not a call to anything in particular—it’s a series of questions that opens the door to anything at all. And in this context—again, this is a Trump rally—we have to remember what “hating losing” has already meant. Trump made the link himself. He said in Erie:

They want to take away our election. We’re leading Biden by a lot. And they want to try and demean and hurt us, all of us. You know, they’re not indicting me, they’re indicting you, I just happen to be standing in their way, that’s all it is.

And then, later:

The Biden administration is trying to make it illegal to even question the results or the outcome of an election. If you question the rigged election you’re a ‘conspiracy theorist’! They don’t want to talk about it. Because they cheated like nobody has ever cheated. But only a party that cheats in elections would try to make it illegal to question them, they don’t want ’em questioned.

Two and a half years after January 6th, with separate indictments reportedly pending for his involvement in the scheme to overturn the 2020 election, Trump is still saying what he was saying then: that the election was rigged and that they had to save America. And Trump has never stopped this message.

And it’s not just the election lies that he continues to repeat. Remember how, at his rally on the morning of January 6th, Trump told the crowd that if Joe Biden were sworn in, “our country will be destroyed and we’re not going to stand for that”? The same kind of existential, life-or-death rhetoric was on offer in Erie: “If these corrupt persecutions of our people succeed, they will complete their takeover of this country and destroy your way of life forever. And you know what, once that happens, this country will be in turmoil, there’s really no coming back. We have one chance to save it. And that chance is called 2024.”

The refrain is that the election was rigged, that the Biden administration is corrupt, and that you, the real American, are being persecuted—that the evil they will “destroy your way of life forever.” As on January 6th, this kind of rhetoric does not explicitly call for violence, but violence is implicit in it. Other people surrounding Trump build off of it, feed off of it, use it as a jumping-off point to threaten actual violence—Charlie Kirk, for instance, who called last week for President Biden to be either put in prison or given the death penalty for the supposed crimes Trump keeps discussing.

And maybe it’s just rhetoric—but when Trump posted a suggestion of former President Obama’s home address on Truth Social, a QAnon conspiracy theorist and January 6th attacker went after Obama with rhetoric suggesting an assassination attempt during his livestream.

It’s always just rhetoric until the murders become real, not performative.

AT THE END OF TRUMP’S ERIE RALLY, one of the songs in the playlist reminded QAnon adherents of their song, “#WWG1WGA,” or “Where We Go One, We Go All” (a similarity first noticed last year). And although we pay less attention to QAnon nowadays, it’s worth remembering that its adherents haven’t disappeared, and that the heart of QAnon’s fictional eschatology is a murder fantasy, too, the fantasy that all of their opponents will be rounded up and killed by the government.

This is the grotesque vision that unites these things—a Jason Aldean song, a Trump rally, and QAnon: What they want is a different world, a purified world in which all of the people unlike them are gone. And gone with violence. Each of them invites or at least imagines violence done to their opponents to drive them out of their utopian future.

What they all hope for, though, is that someone else will do the dirty work for them.

What if the rhetoric keeps spreading, keeps moving into mainstream spaces and conversations and political discourse?

And what if Trump’s supporters lose in 2024?

And what if, as on January 6th, some of them take the violent vision seriously enough to act on it?

And what if, one bloody day, it isn’t just rhetoric anymore?