Trump Says He Shouldn’t Be Tried with an Election Pending

Brazenly asks the Supreme Court to buy into his strategy of delay.

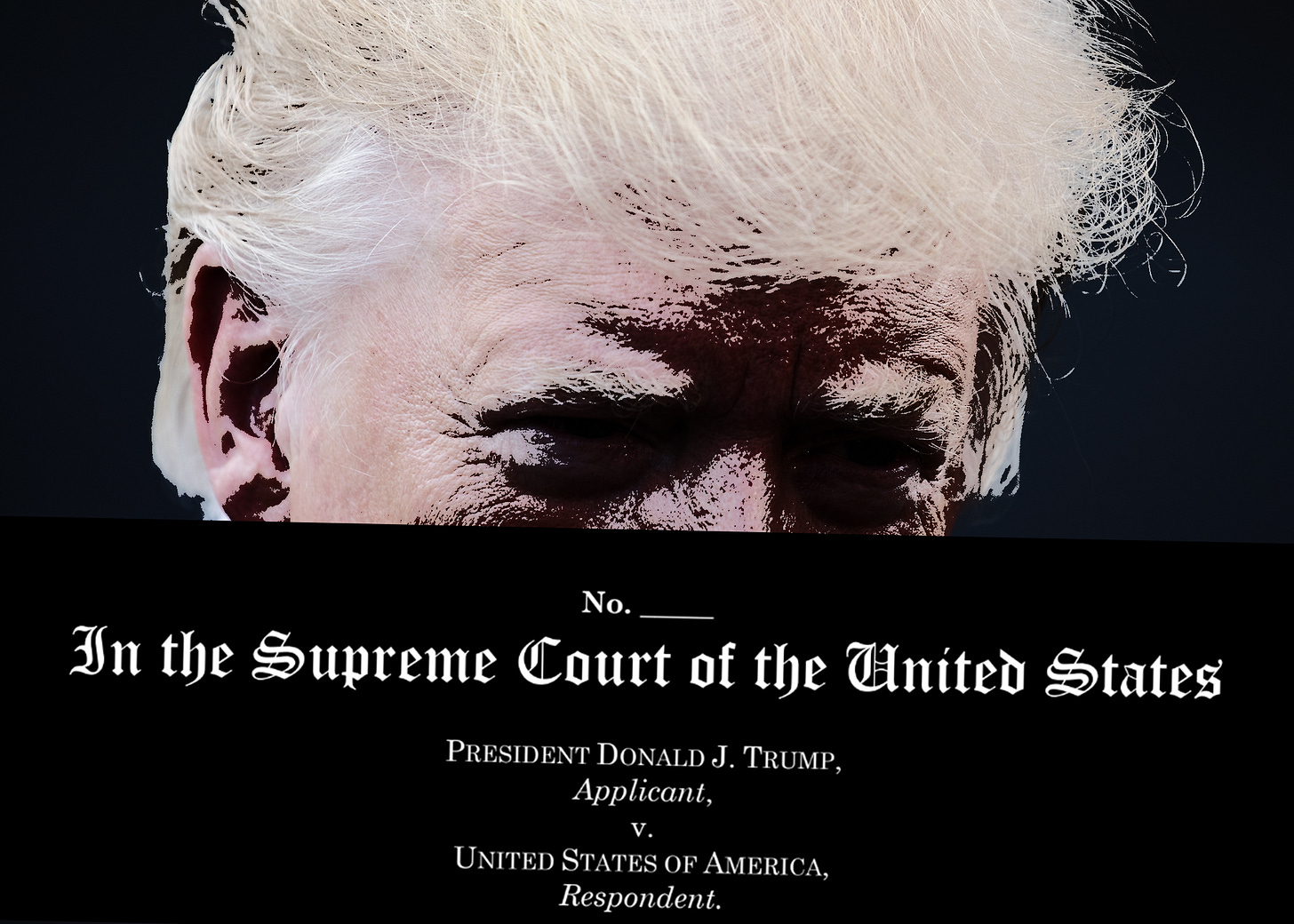

ON MONDAY, DONALD TRUMP FILED an application with the U.S. Supreme Court seeking an indefinite stay of the January 6th criminal trial that had been scheduled for March 4 in Washington, D.C. Trump’s request to halt the trial is the precursor to his next move: an anticipated appeal of the decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit rejecting his bid for absolute, king-like immunity from prosecution for acts taken while president. The three-judge appellate panel’s ruling has been widely heralded as beautifully reasoned, grounded on sound historical scholarship, and legally bulletproof—which should give the Supreme Court comfort that it can sit this one out and focus on other important matters. Still, there’s no telling what this Court will do with the immunity question.

But Trump’s latest filing is noteworthy for an entirely different reason. In it, he unveils a long-anticipated argument—but one that has not yet appeared prominently in his legal filings—for why the four criminal cases against him should not go forward: The November election is coming.

Anyone who has been paying attention to the Trump trials knows that his best defense in all four cases (the federal January 6th and Mar-a-Lago cases, the Manhattan case, and the case from Fulton County, Georgia) is delay, delay, delay. On the facts and the law, he overwhelmingly loses, with rare exceptions. So what can we expect about the timing of the four cases?

The federal January 6th trial date has already been stalled, and if Trump has his way in the Supreme Court, it will be put on hold even longer.

The Florida case regarding classified documents is set for trial on May 20, but Trump has the favor of the trial judge in that case, U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon, so nobody expects the classified documents case to move forward apace.

The Georgia case is complex and sprawling, and never had any chance of wrapping up before November.

That leaves the 34-count Manhattan “hush money” case—the one everyone howled about as unworthy of a former president back when Manhattan D.A. Alvin Bragg brought it in April of last year—which goes to trial on March 25. It might be the only one of the four trials to make it to a jury before the election.

Which brings us back to Trump’s latest filing in the Supreme Court. In addition to the routine (and erroneous) claims that the D.C. Circuit got the immunity question wrong, his lawyers now argue that the federal January 6th trial “imposes another grave species of irreparable injury—the threat to the First Amendment rights of President Trump, his supporters and volunteers, and all American voters, who are entitled to hear from the leading candidate for President at the height of the Presidential campaign.” Trump goes on to cite a bunch of First Amendment cases that operate more as rhetoric than substance, because as a practical matter, they are unlikely to actually get rid of the criminal indictment—the trial judge would have to dismiss it entirely on First Amendment grounds. But politically, the filing signals a theme that is likely to come up again and again by the Trump team, and likely even his many Republican party enablers, between now and the election. Expect to hear that refrain become a major theme from Trump supporters: These trials are infringing on the rights of Trump and of the American people to choose their president, using the justice system to interfere with free speech and democracy.

Unfortunately, although that argument is bogus, it could have some legs.

The Justice Department has typically followed internal guidelines that frown upon investigations and prosecutions of political actors in the days and weeks leading up to an election. Attorney General Merrick Garland officially continued that policy in a May 25, 2022 memorandum entitled, “Election Year Sensitivities,” in which he states that, despite the government’s “strong interest in the prosecution of election-related crimes,” DOJ “must be particularly sensitive to safeguarding the Department’s reputation for fairness, neutrality, and non-partisanship.” Garland writes that prosecutors “may never select the timing of . . . criminal charges, or any other action in any matter or case for the purpose of affecting any election, or for the purpose of giving an advantage or disadvantage to any candidate or political party.” But it’s not enough to be entirely neutral about the scheduling of investigative and prosecutorial actions: Garland insists that even “the appearance of such a purpose” should be avoided.

The closer the calendar gets to November, the stronger the political argument becomes that DOJ should pull back and let the voters decide for fear of appearing partisan. Garland has drawn sharp criticism for taking so long to appoint Special Counsel Jack Smith or to take other action around Trump’s unlawfulness on January 6th. If he were to bootstrap that historical hesitation into justifying post-election delays of the federal cases, Garland would go down in history as one of the most consequential attorneys general in the history of American democracy—and not in a good way.

Meanwhile, if last week’s oral argument on the question of whether the Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling that Trump is off the ballot under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment is any indication, the U.S. Supreme Court justices are, like Garland, likely to be cagey about taking real steps to hold Trump accountable except at the ballot box. Chief Justice John Roberts, who is the justice responsible for hearing the stay application, gave Smith until 4:00 p.m. on February 20 to respond to Trump’s stay petition, although Smith could file sooner.

If the Court agrees to hear the immunity issue, it might not issue a ruling until June, which puts the January 6th trial in July at the earliest. If it entertains this latest Trump ploy, his immunity gambit could, in theory, wind up foreclosing a trial altogether. The justices should bear in mind the costs of continuing to play Trump’s game of chicken. Maybe the voters will have their say in November, but it’s high time to let a jury of his peers have a say in his personal and political fate.