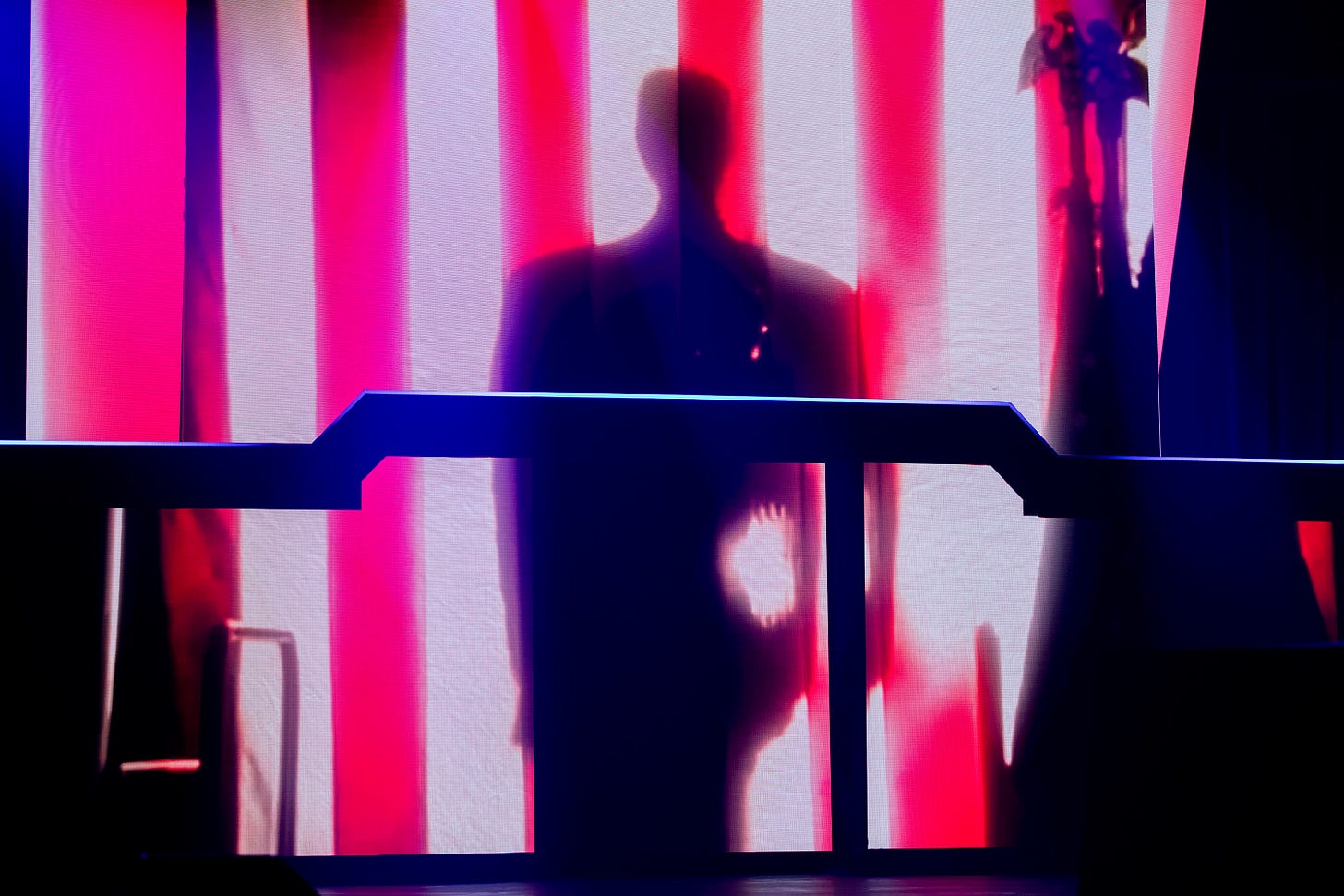

Yes. They’d Vote For Him If He Shot Someone on 5th Ave.

Republicans are redefining their morals to accommodate Trump. The polls prove it.

IN 2016, DONALD TRUMP joked: “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters.”

It’s not a joke anymore. Trump has lost almost no support since he was convicted of 34 felonies in his hush-money trial on May 30. The Republican party remains fully committed to him, and he has held his ground in polls. In fact, since President Joe Biden’s disastrous performance in their June 27 debate, Trump’s lead over Biden has increased.

It’s created a striking contrast between the two parties. While Democrats agonize over Biden’s debate performance—and many call for him to step down as their presumptive nominee—Republicans shrug off Trump’s felonies. But the rot in the GOP goes even deeper. Surveys taken since Trump’s conviction show that to excuse him, many Republicans have adjusted their morals. They’ve decided that when Trump does something bad or criminal, it’s no longer bad or criminal.

Let’s look at these polls. We’ll start with the moral questions.

“Do you think that the following is immoral? Paying someone to remain silent about an affair.”

In a YouGov survey last year, 61 percent of Republicans answered yes to that question. Only 29 percent answered no. But when YouGov repeated the question after Trump’s conviction, the percentage who said yes dropped to 51, and the percentage who said no rose to 36. What had previously been a 30-point margin of agreement on the wrongness of hush money was cut in half.

“Do you think that the following is immoral? Paying someone to remain silent about an issue that may affect the outcome of an election.”

In last year’s YouGov survey, 65 percent of Republicans said yes to that question; 22 percent said no. After Trump’s conviction, only 54 percent said yes, while 29 percent said no. That’s a net shift of 18 points—roughly the same as on the question about paying to cover up an affair.

REPUBLICANS ALSO CHANGED their views on what should count as a crime. Look at these two questions, taken from the same pair of YouGov polls.

“Do you think that the following should be illegal? Paying someone to remain silent about an affair.”

Last year, 36 percent of Republicans said yes. After Trump’s conviction, that number fell to 21 percent.

“Do you think that the following should be illegal? Paying someone to remain silent about an issue that may affect the outcome of an election.”

Last year, 55 percent of Republicans said yes; only 31 percent said no. But after Trump’s conviction, the gap vanished. Republicans were almost evenly split, 41 percent to 39 percent.

Another series of polls, taken this year by YouGov for Yahoo! News, found something similar. They asked: “Do you consider the following to be a serious crime? Falsifying business records to conceal hush money payments to a porn star.”

In April, before Trump’s trial, 27 percent of Republicans said yes. In mid-May, four weeks into the trial, the pollster tweaked the question slightly— “Do you consider falsifying business records to conceal hush money payments to a porn star a serious crime?”—and the percentage of Republicans who said yes fell to 18 percent. In June, after the verdict, the wording of the question didn’t change, but the slide continued: Only nine percent of Republicans said yes. In the same series of polls, the percentage of Republicans who said it wasn’t a serious crime rose from 54 to 63 to 77.

Republicans weren’t entirely alone in modifying their answers to these questions. In some cases, Democrats moved in the other direction, raising their moral or legal standards to punish Trump. It’s partisan tribalism. But the tribalism is measurably stronger on the right. In most cases, the Republican shift was at least three times bigger than the shift among Democrats or independents. And often, Democrats and independents shifted minimally or not at all.

AS REPUBLICANS LOWERED their standards on morality and crime, they also became more flexible about whether a criminal record should disqualify a presidential candidate.

“Do you think that someone who has been convicted of a felony should be allowed to be the president?”

In an April YouGov survey, only 17 percent of Republicans said yes to that question; 58 percent said no. But after Trump’s conviction, the numbers turned upside down. Fifty-eight percent of Republicans said yes; only 23 percent said no.

“Are there any circumstances in which you would be willing to vote for someone convicted of a felony who is running for president?”

When YouGov asked that question in April, 49 percent of Republicans said yes; 37 percent said no. After the verdict, 74 percent of Republicans said yes; only 14 percent said no.

One sign of Republicans’ devotion to Trump is that their increased willingness to elect criminals doesn’t extend equally to all offices. In the same two surveys that asked about electing a felon as president, YouGov also posed the following question: “Are there any circumstances in which you would be willing to vote for someone convicted of a felony who is running for city council?”

After Trump’s conviction, Republicans were more likely than before to say that they could envision voting for a felon for city council. But the percentage who expressed that view rose only to 63 percent—11 points shy of the number who said they could vote for a felon as president.

That seems bizarre. Why would some Republicans be more willing to elect a felon to the presidency than to a city council? The obvious answer is that these respondents aren’t focusing on which office is more important. They’re focusing on justifying a vote for Trump.

WHEN POLLSTERS ASK SPECIFICALLY about Trump, they find the same result: Many Republicans switched their positions after his conviction.

“If all other things were equal, would you vote for Donald Trump for president in 2024 if he [is] convicted of a felony crime by a jury?”

In April, Ipsos asked that question in a survey for Reuters. Forty-nine percent of Republicans said they would still vote for Trump; 24 percent said they wouldn’t. But when Ipsos repeated the question after Trump’s conviction, 66 percent of Republicans said they would still vote for him. Only 14 percent said they wouldn’t.

“If Donald Trump is convicted of a crime in this case, do you think he should be allowed to serve as president again in the future?”

When Yahoo posed that question last year after Trump was indicted in the hush-money case, only 56 percent of Republicans said he should be allowed to serve; 24 percent said he shouldn’t.

But when Yahoo updated the question in June—“Now that Donald Trump has been convicted of 34 felony counts of falsifying business records, do you think he should be allowed to serve as president again in the future?”—85 percent of Republicans said he should be allowed to serve. Only eight percent said he shouldn’t.

TO EXCUSE TRUMP, Republicans haven’t just softened their standards over time. They also hold him to a lower standard than they apply to other presidents, presidential candidates, and even ordinary voters.

“Do you think U.S. presidents should have immunity from criminal prosecution for actions they take while serving as president?”

When CBS News asked that question in a poll after Trump’s conviction—to half of a 2,000-person sample—most Republicans said no: 55 percent to 45 percent. But in the same poll, when the other half of the sample was asked a different version of the question—“Do you think Donald Trump should have immunity from criminal prosecution for actions he took while he was president?”—67 percent of Republicans said yes.

In YouGov’s first post-conviction poll, mentioned above, 58 percent of Republicans said yes when they were asked: “Do you think that someone who has been convicted of a felony should be allowed to be the president?”

But here’s another question from the same poll: “Do you think Donald Trump should be allowed to serve as president again in the future, given his recent felony conviction?” When the question was put that way—about Trump, not presidential candidates in general—78 percent of Republicans said yes. Again, that’s a 20-point double standard in Trump’s favor.

In fact, some Republicans, while refusing to disqualify Trump for his crimes, would disqualify voters for having done the same thing. In YouGov’s post-conviction poll, when Republicans were asked, “Do you think that someone who has been convicted of a felony should be allowed to vote in presidential elections,” 58 percent said yes, and 21 percent said no. In other words—again by a margin of 20 points—Republicans were more willing to let their favorite felon serve as president (Trump) than to let other felons vote on whether he should be president.

One more notable finding in these polls: Self-identified evangelical Christians—people who purport to serve a deity higher than Trump—nevertheless reversed some of their stated moral positions after his conviction. In the April Yahoo/YouGov survey, taken just before Trump’s trial began, evangelicals agreed by a margin of nearly 20 points—53 percent to 34 percent—that falsifying business records to conceal hush money payments to a porn star was a serious crime.

A month later, well into the trial, that margin had collapsed: 42 percent said it was a serious crime, but 39 percent said it wasn’t. And by June, after the verdict, the balance was reversed: 46 percent of evangelicals said it wasn’t a serious crime; only 36 percent said it was.

Evangelicals also revised their positions on questions specific to Trump. Last year, when a Yahoo/YouGov survey asked whether Trump should be allowed to serve as president if he were convicted of a crime in the hush-money case, evangelicals were more likely to say that he shouldn’t be allowed (43 percent) than that he should (37 percent). But in June, when they were asked the same question with one new factor—“now that Donald Trump has been convicted of 34 felony counts”—they switched to Trump’s side. Fifty-two percent of evangelicals said he should be allowed to serve; only 34 percent said he shouldn’t.

As many Democrats press Biden to withdraw from the race, what comes across from these post-conviction polls is a stark difference between the parties. One party, presented with evidence that its leader has cognitively declined, is trying to replace the leader to meet the party’s standards. The other party, presented with proof that its leader committed felonies, is lowering the party’s standards to accommodate the leader. That’s the difference between a party that will stand up to an autocrat and a party that won’t.