Trump’s Muddled Foreign Policy Thinking—and Ours

It’s been too long since America’s leaders have tried to articulate a consistent, coherent view of the world and our country’s role in it.

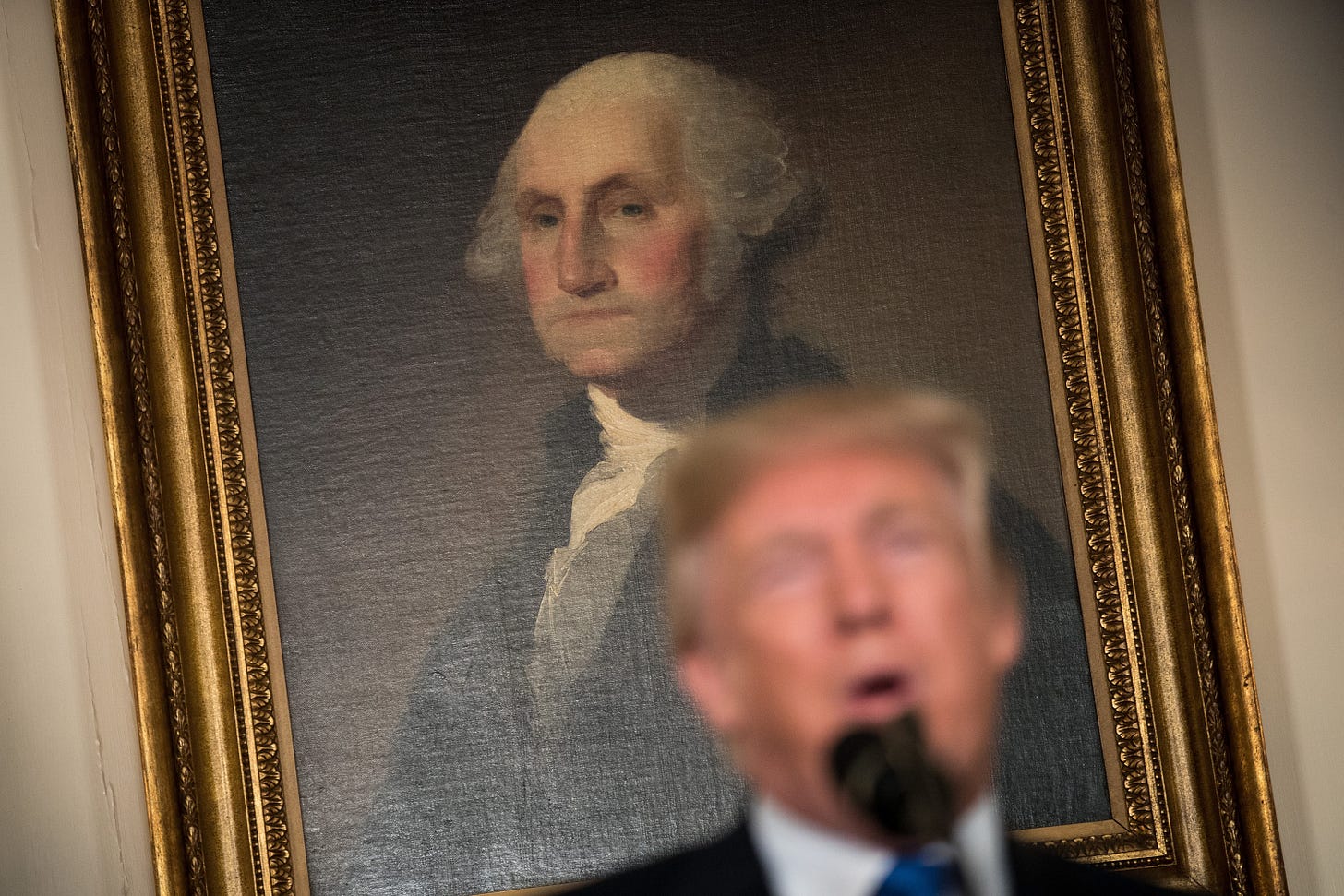

There are two basic problems with President Trump’s handling of foreign affairs. (Well, maybe three, if you count unabashed corruption, but that pervades his domestic affairs as well.) One problem is unique to him. The other is more widespread and entrenched—and therefore more troubling.

The first is that the president is completely, proudly, and incurably ignorant about most of the world.

Now, usually the disease of ignorance can be treated with a regimen of book-reading. For the president, it’s even easier: The United States spends close to $60 billion on intelligence programs that all eventually feed a customized report for the president delivered each day, the President’s Daily Brief. The brief is delivered by briefers—trained intelligence professionals backed by teams of technical and substantive experts—whose job it is to present information about the world to the president in whatever way he finds easiest. If the president wants written reports, he can get written reports. If he wants maps and pictures, he can get those. In-person briefings—no problem. Video, no sweat. And the briefers are prepared to answer, or get answers to, any questions the president may have.

But this entire apparatus assumes that the president wants more information than he has. Based on this story drawn from the new book A Very Stable Genius, in which President Trump throws a temper tantrum directed at his entire foreign policy team in the Pentagon, it doesn’t appear that he does:

Trump appeared peeved by the schoolhouse vibe but also allergic to the dynamic of his advisers talking at him. His ricocheting attention span led him to repeatedly interrupt the lesson. He heard an adviser say a word or phrase and then seized on that to interject with his take. For instance, the word “base” prompted him to launch in to say how “crazy” and “stupid” it was to pay for bases in some countries.

This is a failure of personality which, luckily, can be overcome by replacing the person.

The second problem is much trickier, since it relates not just to President Trump but, in a sense, to the American people. Back to the episode from the Pentagon:

Trump seemed to be speaking up for the voters who elected him, and several attendees thought they heard Bannon in Trump’s words. Bannon had been trying to persuade Trump to withdraw forces by telling him, “The American people are saying we can’t spend a trillion dollars a year on this. We just can’t. It’s going to bankrupt us.”

“And not just that, the deplorables don’t want their kids in the South China Sea at the 38th parallel or in Syria, in Afghanistan, in perpetuity,” Bannon would add, invoking Hillary Clinton’s infamous “basket of deplorables” reference to Trump supporters. As objectionable as Bannon’s political outlook and sartorial sense may be, he may be right on this point. Mutual defense commitments with NATO allies, stationing troops in South Korea and Okinawa and Bahrain, intervening to secure countries Americans probably can’t find on a map, and deterring countries they definitely can’t—it’s not clear that a plurality of Americans understand these policies, much less support them.

In a Gallup survey conducted last year, 77 percent of the respondents (weighted demographically) said that the NATO alliance should be maintained, while only 69 percent said America should play a “major role” or the “leading role” in the world. Which means that at least 8 percent of the respondents, and perhaps more, believe that the United States should continue to form the backbone of the most powerful and successful military alliance in the history of the world but should not play a major role in world affairs.

Americans can’t be expected to wisely evaluate foreign policy proposals or international developments if they lack an understanding of America’s role in the post-WWII world and what it means to be the indispensable country.

After all, it’s been a while—for some of us, a lifetime—since American leaders have articulated a consistent, coherent view of the world and the country’s place in it. We failed to reach a lasting consensus about it in the 1990s as we celebrated the end of history. After 9/11, we spent a lot of time and energy thinking and talking about Islamist terrorism and democracy in the Middle East—but whether or not that was myopic is open to debate.

Far too few American leaders—arguably none since the death of John McCain—have offered the American people the sort of explanation for an active American role on the world stage that Secretary of Defense James Mattis tried to give President Trump that day in the Pentagon:

An opening line flashed on the screen, setting the tone: “The post-war international rules-based order is the greatest gift of the greatest generation.” Mattis then gave a 20-minute briefing on the power of the NATO alliance to stabilize Europe and keep the United States safe. Bannon thought to himself, “Not good. Trump is not going to like that one bit.” The internationalist language Mattis was using was a trigger for Trump.

It’s obvious now that President Trump would never grasp that the American-led international order is the greatest geopolitical accomplishment in the history of the world—nor that, as the central node in the web of military alliances and free trade, the United States has done very well by doing good.

But maybe more Americans would understand the benefits and responsibilities of America’s role leading the world if only someone would enunciate it. Pete Buttigieg—basically alone among the Democrats—has come close. Republicans in Congress have barely tried.

That’s no way to run a superpower.