Ukraine Dam Disaster: What Does It Mean for the War?

What we know so far—and what we still need to know.

THE NOVA KAKHOVKA DAM, a massive concrete wall across the Dnipro River in the middle of Ukraine, collapsed Tuesday, threatening to flood large portions of southern Ukraine along both sides of the front lines. We know a little; we can predict a little more about what this might mean for the war in Ukraine; and we can suspect, with caveats, who might be at fault.

What We Know

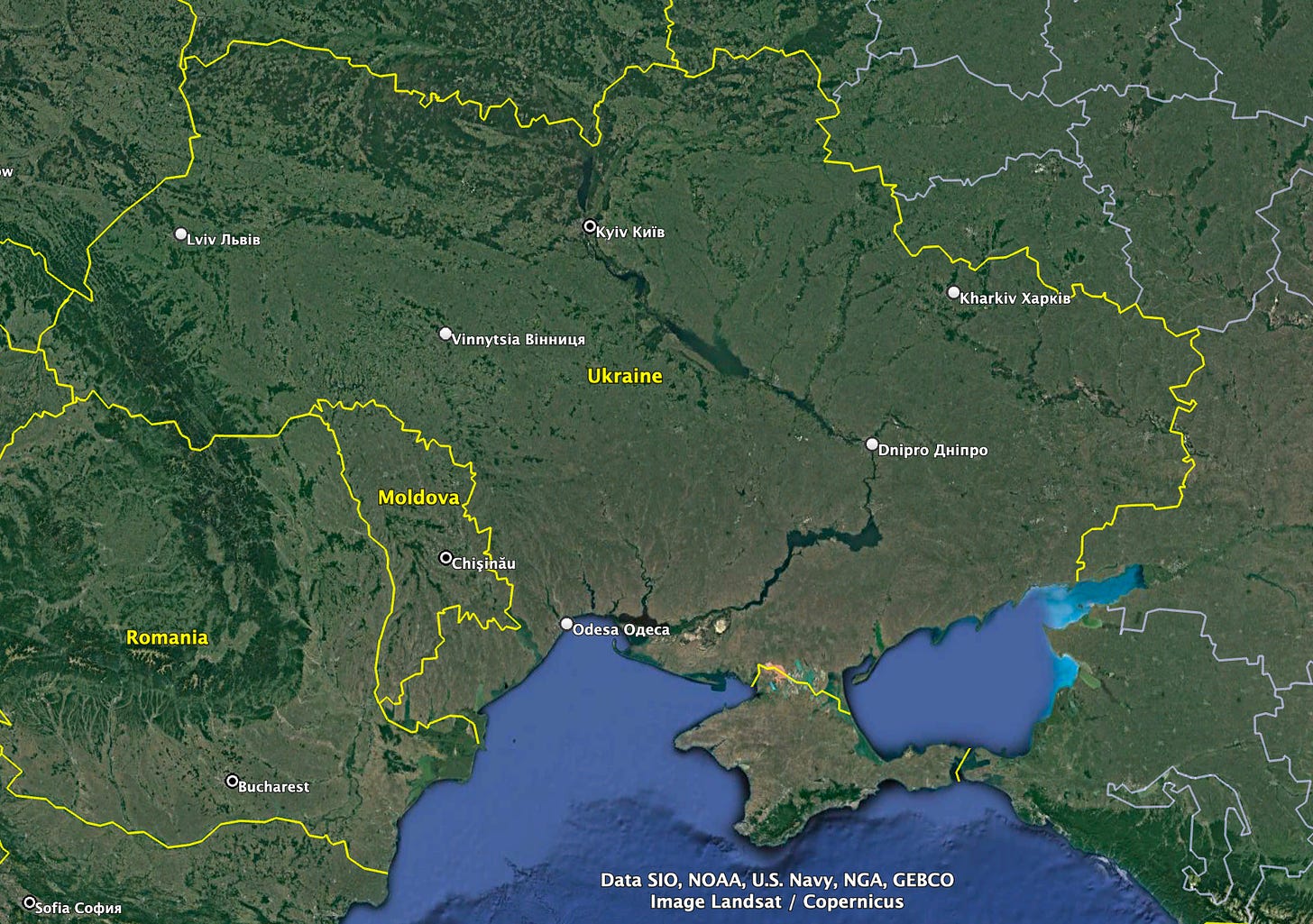

Take a look at Ukraine, pictured here in a satellite image from Google Earth:

Running right through the middle of the country, dividing it more or less vertically, is the massive Dnipro River. One of the reasons it appears so large is that it is punctuated by a series of reservoirs created by dams like Nova Kakhovka, which was built in 1956 as a hydroelectric dam. In addition to providing electricity, it also holds back an enormous quantity of water—the Kakhovka Reservoir is the southernmost reservoir in the map above.

To get a better idea of how big the dam is, take a look at it from about 80,000 feet.

The dam is about 100 feet high and two miles across, and it holds back more than four cubic miles of water at its peak capacity. It was probably close to peak capacity when the dam broke—in May, the water in the reservoir rose so high that it flooded over the top of the dam.

The image above captures part of the front lines of the war in Ukraine. Although the river overall flows north to south, at this point it flows east to west (right to left in this image). The Ukrainians control the side at the top of the photo; it’s where the town of Kozat’ske is. The Russians control the other side, where the town of Nova Kakhovka is, although the Ukrainains have raided Nova Kakhovka itself, and the Institute for the Study of War marks the town as a location of “reported Ukrainian partisan warfare.”

Note the canal running southward from the Dnipro River, the straight, dark line pointing down in the bottom right of the image above. That canal runs all the way to Crimea, supplying the semi-arid, Russian-controlled peninsula with water. After the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Ukrainians dammed the canal. The Russians restored the water flow after retaking the canal during their full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Draining the Kakhovka Reservoir too far—which could happen now that the dam is destroyed—could cut off that water supply again.

The Kakhovka Reservoir also supplies water to cool the Russian-controlled Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, but the U.N.’s International Atomic Energy Agency reports that the destruction of the dam poses “no immediate risk” to the power plant. The power plant, which is about 80 miles upstream from the dam, has been deactivated since last year, but the nuclear fuel inside still needs to be kept cool to prevent a meltdown.

What We Can Predict

The most obvious prediction is that there will be flooding. Lots of it. How much, where, and when depends on how much of the dam was destroyed and how high the reservoir and river were when the dam broke. One preliminary model suggested a wave 13 to 16 feet high could reach the Antonovsky Bridge east of Kherson, about 30 miles downstream from the Nova Kakhovka Dam; a note appended after publication stated that the water level in the dam was higher than the model had accounted for. In the worst-case scenario, large portions of the banks of the river would be flooded, and the extra water pouring into the Black Sea could cause flooding in other rivers, too, including possibly up the Bug River to the city of Mykolaiv. The government of Ukraine is eager to add Mykolaiv to the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which would allow it to export far greater quantities of grain—but perhaps not if the port is flooded.

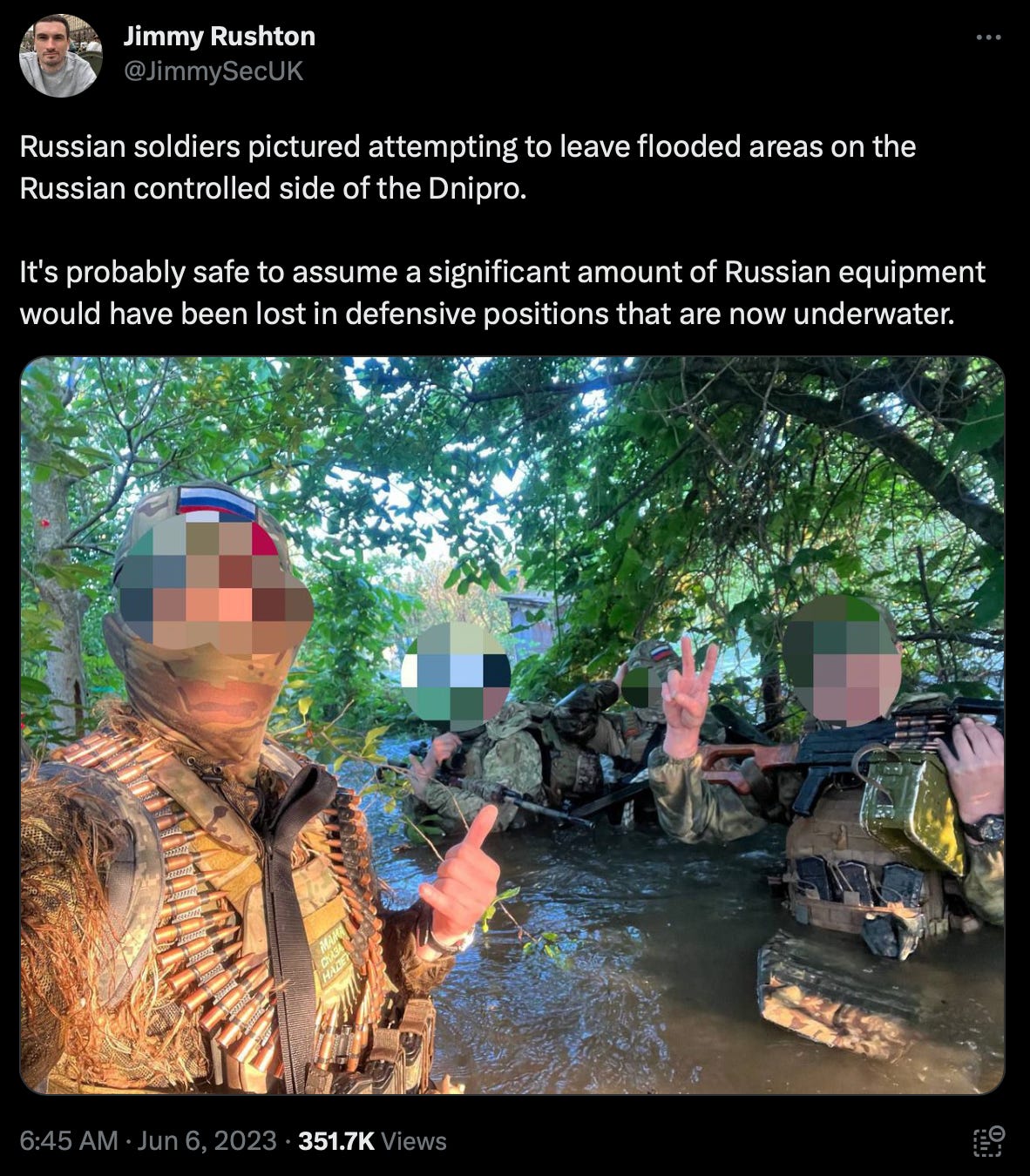

The same model predicts that the worst of the flooding would occur on the Russian-controlled side of the Dnipro. Anecdotal reports already suggest that Russian forces are struggling to react to rising water levels.

This doesn’t mean that the Ukrainian military will benefit from the dam’s destruction. It may have begun preliminary probing of Russian defenses in Donetsk, where the front lines are far from the Dnipro, but it is highly likely that Ukraine’s plans for its long-awaited counteroffensive also called for amphibious operations across the river into Russian-controlled territory. Ukrainian military plans are also likely to be affected by damage to or flooding out of infrastructure along the river—roads, bridges, buildings, embankments, etc. that may be compromised or washed out.

Aside from the military considerations, Ukraine is also losing a major source of power generation. After weathering months of Russian air attacks on its energy infrastructure with missiles, bombs, and drones, it may have just permanently lost 334.8 MW of power generation. That’s not a ton—the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, when it is active, generates 5,700 MW—but Ukraine isn’t in a position to be giving up sources of electricity.

Moreover, the environmental implications will be enormous. As if the effects of the war itself weren’t bad enough for Ukraine’s lands, waters, atmosphere, flora, and fauna, the flood will disrupt huge swaths of the Dnipro system.

What We Can Suspect

Cui bono? The Institute for the Study of War, while declining to attribute responsibility, noted months ago that the Russians would stand to gain more from blowing up the dam than the Ukrainians—though at that time, when the Russian army was retreating across the Dnipro from Kherson, a dam failure posed less of a risk to their own forces on the left bank of the river.

The Russian government has blamed the Ukrainians for blowing up the dam, and the Ukrainians have blamed the Russians. Izvestia, the Russian government-sponsored “news” organization, claims to have video of the Ukrainian military attacking a dam, although the low-definition, nighttime video only shows a dam exploding.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky warned back in October that Russian forces were mining the dam. That same month, texts reportedly from someone connected to Russia’s 205th Motorized Rifle Brigade included descriptions of mining the dam. The Ukrainian government has now assigned responsibility to the same unit. Zelensky stated Tuesday, “It is physically impossible to blow it up somehow from the outside, by shelling. It was mined by the Russian occupiers. And they blew it up.” As the blogger for the Institute for the Study of War noted, if the Russians planned to destroy the dam, they would likely do so as part of a false-flag operation, blaming it on the Ukrainians.

Although assessments may change as more facts come to light, at this point it’s hard to see why the Ukrainians would destroy the dam. Kremlin spokesman Dmitri Peskov offered that the Ukrainian counteroffensive had sputtered out after just two days, and “sabotage” against the dam was an act of wanton desperation. This description seems more apt for the Russians, who have lost all momentum and now await the Ukrainian counterattack, which will reportedly consist of between eight and 13 new brigades, or anywhere from 24,000 to 65,000 soldiers. If anyone was in need of a desperate, last-minute way to change the status quo, it was the Russians, not the Ukrainians.