Violence in the Capitol: A Historic Wake-Up Call

Pictures of the insurrectionist attack evoke the infamous caning of Charles Sumner—and its troubling context.

After weeks of decrying the election as fraudulent, coupled with years of sowing political mistrust and chaos, President Donald Trump’s unwillingness to relinquish power and subversion of the constitutional order were laid bare for all to witness on Wednesday when an insurrectionist mob stormed the U.S. Capitol in his name.

A dark streak of American history also ran through last week’s riot. Numerous individuals who breached the Capitol carried Confederate flags—the symbol adopted by those who sought to break with the United States for the purpose of defending and perpetuating slavery—for the first time in the nation’s history. In a haunting image captured by photographers Saul Loeb of AFP (above) and Mike Theiler of Reuters, we watched a man carry the Confederate flag in front of a portrait of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. As noted Civil War historian Judith Giesberg told Business Insider, “What that image should remind us of is that there’s a history of having violent political confrontations in Congress.”

The portrait of Sen. Charles Sumner (1811-1874) that hangs in the Capitol, painted by Walter Ingalls in 1873. (Via the U.S. Senate)

Born in Boston in 1811, Sumner was raised in an antislavery household. He was among the “Conscience Whig” faction that rejected the party’s accommodation with slavery. In 1847, Sumner declaimed against the Mexican-American War as “a war for the extension of slavery over a territory which has already been purged, by Mexican authority, from this stain and curse.” In 1848, the Whigs nominated the war hero and slaveholder Zachary Taylor for president. Sumner had seen enough: he bolted to the short-lived antislavery Free Soil Party, a coalition born of Barnburner Democrats, Conscience Whigs, and the Liberty Party.

Sumner was quick to make enemies in his political career. Beyond attacking Southerners, he also decried the complicity of Northerners in maintaining and profiting from slavery. Like many antislavery politicians and activists, he charged that the American political system was being held hostage by an “unhallowed union” of “the cotton-planters and flesh-mongers of Louisiana and Mississippi and the cotton-spinners and traffickers of New England.”

Sumner remained an outspoken opponent of slavery after his election to the Senate in 1851. In the midst of the violent “Bleeding Kansas” crisis—in fact, on the eve of the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas in 1856—Sumner took to the Senate floor to deliver his blistering speech “The Crime Against Kansas.” Comparing slaveholding politicians and their enablers living in free states to oligarchs, Sumner blasted at those who supported “the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery.”

But Sumner did not just attack in broad strokes; he personally attacked Senators James Mason of Virginia, Stephen Douglas of Illinois, and Andrew Butler of South Carolina. Sumner compared Butler to the deluded Don Quixote and accused the South Carolina slaveholder of taking “the harlot Slavery” as his “mistress.”

Sumner’s speech sparked an immediate backlash that soon became the talk of the capital. Thomas Rivers, a congressman from Tennessee, reportedly said that “Mr. Sumner ought to be knocked down, and his face jumped into.” The Washington Star defended Senator Butler, calling Sumner’s rhetorical attacks on him “unjust and untrue” and arguing that his language “caused a blush of shame to mantle the cheeks of all present.” Even some of Sumner’s Republican allies believed that he had gone too far with this rhetoric, fearing the political fallout and possible threat to his personal safety.

Two days later, there followed one of the most infamous and troubling incidents in the history of the U.S. Congress. While Sumner was sitting at his desk on the Senate floor, he was approached by Preston Brooks, a South Carolinian congressman and a relative of Butler’s. Addressing Sumner, Brooks said, “I have read your speech twice over carefully, it is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.”

Brooks struck Sumner across the head with his gutta percha cane. The first blow stunned Sumner, who tried to defend himself but soon collapsed amid the onslaught of blows from Brooks. Onlookers were unable (and in some cases unwilling) to assist Sumner, since Brooks was accompanied by armed House colleagues South Carolinian Laurence Keitt and Virginian Henry Edmunson. According to Brooks, “towards the last [Sumner] bellowed like a calf. I wore my cane out completely but saved the head, which is gold.”

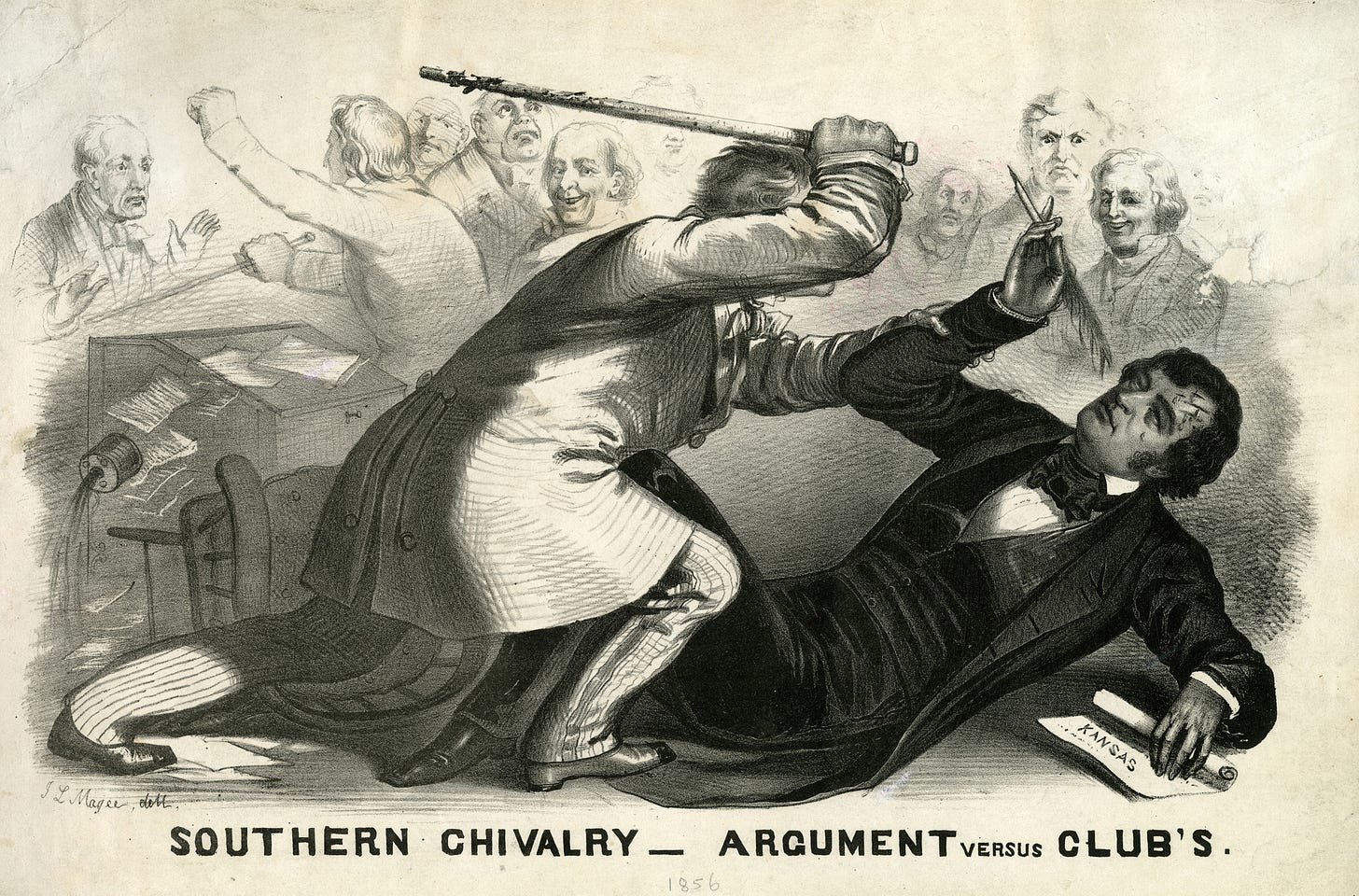

Famous depiction of the beating of Sen. Charles Sumner by Rep. Preston Brooks in the Senate chamber. (Lithograph by J.L. Magee, via the New-York Historical Society / Getty)

Southerners widely celebrated Brooks’s actions. Sen. Robert Toombs of Georgia (the future Confederate secretary of state) witnessed the assault and roundly approved. “Our approbation . . . is entire and unreserved,” printed the Richmond Enquirer, going on to compare Sumner’s beating to the beating of a dog:

These vulgar abolitionists in the Senate are getting above themselves. They have been humored until they forget their position. They have grown saucy, and dare to be impudent to gentlemen! Now, they are a low, mean, scurvy set, with some little book learning, but as utterly devoid of spirit or honor as a pack of curs. Intrenched behind “privilege,” they fancy they can slander the South and insult its Representatives, with impunity. The truth is they have been suffered to run too long without collars. They must be lashed into submission.

Brooks and his chief accomplice Keitt both resigned from Congress, but they were each quickly re-elected to their House seats. Back home, South Carolinians welcomed Brooks as the guest of honor at numerous parties and presented their hero with canes to replace the one broken while assaulting Sumner. One such cane bore the inscription “Hit him again.” Brooks crowed that “the fragments of the stick are begged for as sacred relics.” Upon Brooks’s untimely death of croup in 1857, Georgia named a county after him. Keitt went on to serve in the provisional Confederate Congress before fighting in the Confederate Army until his death at the Battle of Cold Harbor.

The assault on Sumner galvanized Northerners and produced a backlash that rallied people to the Republican cause. Moderate and conservative Northern Whigs, Democrats, and Know Nothings now joined the fight. Antislavery meetings and rallies surged in attendance. Black abolitionists organized a meeting at Boston’s Twelfth Baptist Church where they joined in prayer for Sumner and decried the attack on “our senator” as a “dastardly attempt to crush out free speech.”

The caning of Charles Sumner drove home for many Americans just how much politics had changed in the nineteenth century. The crime against Sumner exposed deep divisions within the country and proved how far slaveholders would go to silence their critics and defend their property in human beings. Historian William E. Gienapp saw in the attack a turning point in the Republican party’s development: “Just as the Sumner assault allowed Republicans to moderate and broaden their appeal, so it proved a powerful stimulus in driving moderates and conservatives into the Republican party.” It was the shock to the system Northerners needed to rally around the still-young party.

Wednesday’s insurrectionist attack on the Capitol is part of a long history of threatened and actual violence in Congress; Yale University historian Joanne Freeman, in her recent book The Field of Blood, recounts everything from fistfights, stabbings, and duels. While members of Congress are less likely to resort to physical violence today, a brawl nearly broke out on the House floor this week during the counting of the Electoral College votes, and Lauren Boebert, a Trump-supporting freshman representative from Colorado, has reportedly inquired about carrying a firearm into the Capitol.

Just as the assault on Sumner finally alarmed many contented Northerners to wake up to the dangers presented by slaveholding Southerners willing to resort to violence, this week’s mob attack of the Capitol has finally turned some Trump supporters toward recognizing—or admitting—the danger he poses to the republic. A key question remains how the base of the Republican party will respond to Wednesday’s events: Will they see it as discrediting Trump and Trumpism, or will they see it as the first shot in a conflict they expect to grow worse?