1. MOAR Censorship!

A few years ago I was invited to sit on a panel at the Gathering of the Twitters. It was an all-hands, week-long festival for the company and sitting right up front was @Jack. He even took a picture of me and tweeted it out. It was kind of surreal.

Anyway, the other journalists on the panel talked about how they integrate Twitter with their work. I used my time to to make the case that Twitter should ban people from the platform more aggressively and ignore any complaints from the media—especially from conservative media—for doing so.

There was some nervous laughter in the convention center at this. My argument was that Twitter was not a public utility, that the user experience on the platform was degraded by the presence of bad actors, and that the people who run Twitter are just as qualified to make judgments about what’s useful for a healthy community as anyone else. Because this wasn’t rocket science. It wasn’t even moral philosophy. They didn’t need Chidi Anagoney: 99.9 percent of the cases where a user ought to be banned were little more than common sense.

I made this argument again in 2018 after Apple, Facebook, and YouTube kicked Alex Jones off their platforms. Because if we’re going to try to harness the benefits of new technology, we have to be clear-eyed about attempting to mitigate its dangers. This is the process that has followed the implementation of basically every new technology, ever—from the printing press to the automobile to the vaccine to the telephone.

There was never any reason to believe that social media should be different, that it should be allowed to remain in a state of nature, forever.

We have seen the societal benefits of social media and we have seen the societal costs. It would be madness not to try to decrease the latter and increase the former.

Such attempts will be imperfect and ongoing. They will require some actions taken independently by private companies and some actions taken by government. There will be constant re-balancing.

But anyone who says that tech companies must simply throw their hands in the air and let the masses do what they will is either a salesman, a nihilist, or a fool.

Make Josh Hawley cry. Join Bulwark+

2. A ToS Is Not a Suicide Pact

Twitter and Facebook are American companies. They are headquartered in America. They are subject to the laws of the United States. They have a vested interest in the United States continuing to exist as a stable democracy, because that means that these companies will be subject to the rule of law—which will allow them to operate in an environment that is reasonably predictable and rational.

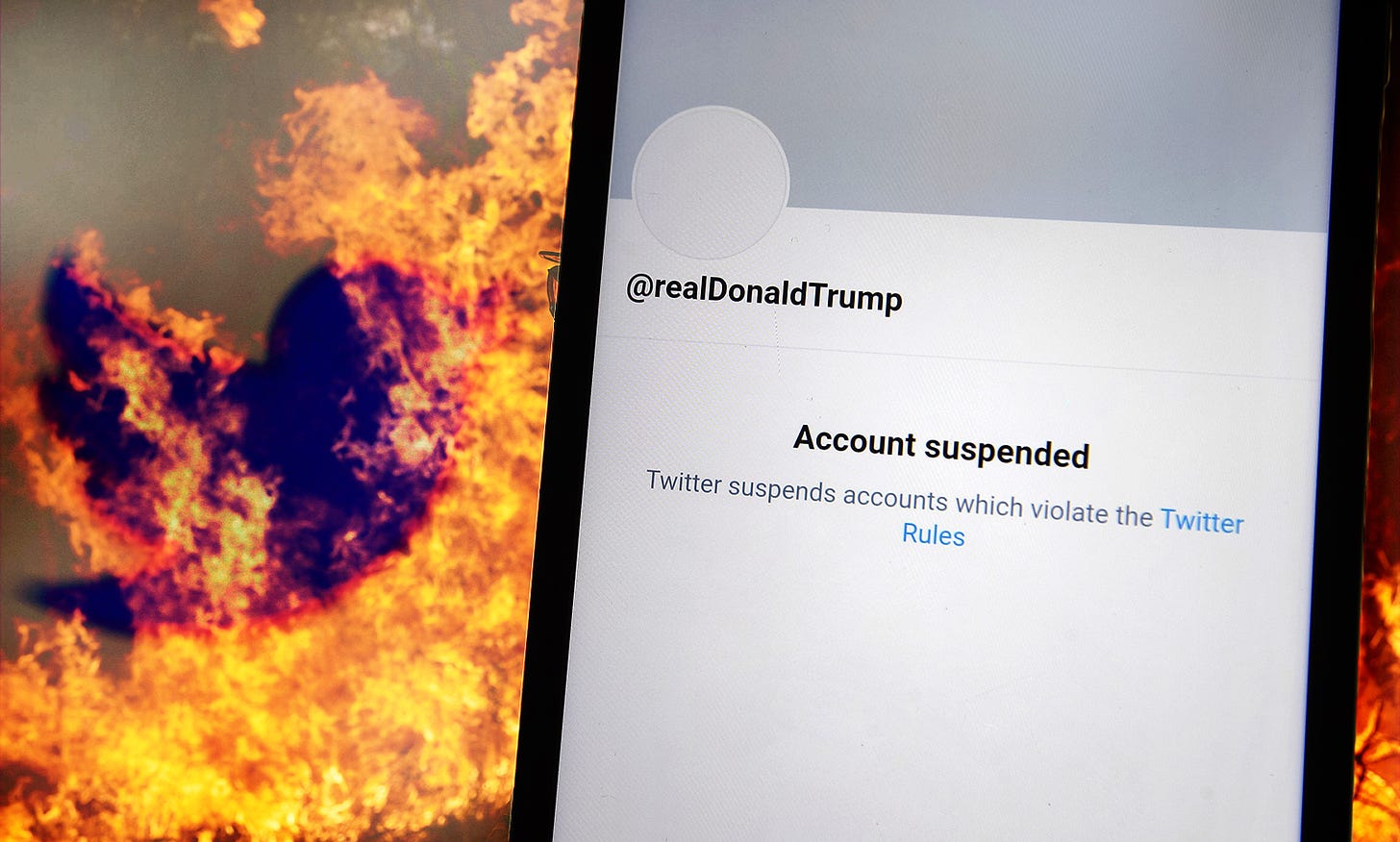

Over the last few months, many people—including the president of the United States—have used these platforms to advocate for an overturning of the government. They have used these platforms to organize an attempt to throw out the results of a free and fair election and install Donald Trump as an illegitimate, autocratic leader.

Had this attempt been successful, it would have been the end of American democracy and, consequently, the failure of the rule of law. This would have had dire consequences for Twitter, Facebook, and every company in America because it would have meant that they were no longer subject to the predictable process of the rule of law, but rather existing at the pleasure of a strongman.

Should Twitter and Facebook be forced to provide their free services to people trying to destroy the government which provides stability for their business?

The Constitution is not a suicide pact and neither are the Terms of Service.

The arguments against de-platforming are not strong.

The first is that it is tantamount to “censorship.” This is obviously immaterial—private companies are not compelled to promote speech and do not have the power to stop speech. Censorship is a government function.

The second is that tech companies do not apply standards with perfect uniformity. Here is the thing about “standards” created by private companies: They are not “laws.” A law must be applied uniformly because it is backstopped by the full power of the state. A “standard” created by a private company is nothing more than a guideline used to explain what are, by definition, subjective judgments.

What’s more, these “standards” do not exist in order to protect the imaginary “rights” of individual users.

They exist in order to make the experience of the wider community better by discouraging users whose behavior is detrimental to the platform.

It’s best to think of terms of service agreements less like “laws” and more like player contracts in the NFL: They are inherently one-sided and subject to alteration.

The third objection is a question of reasonable accommodation: If Twitter kicks Donald Trump off, does he have recourse to other forms of communication?

The answer here is clearly: yes.

While Trump complains about not being able to tweet, here are some of the ways he could communicate with the public:

Walk into the press briefing room at literally any minute of the day or night and start talking.

Call in to Fox, or Newsmax, or OAN—again, at any moment.

Write an op-ed and send it to the Wall Street Journal to run on their opinion page.

Tape a video, or a podcast, and post it on WhiteHouse.gov.

These modes of communication require more than an iPhone and two thumbs, but not much more. And their potential reach is roughly equivalent. This is little more than a case of Trump asking one bakery to make him a cake for White Pride Day, being refused, and having to walk across the street to another bakery, which readily obliges him.

The most salient underlying fact of the internet is that it reduces marginal cost to zero. And because of this, the reasonable accommodations available for Trump are available to basically everyone.

You got kicked off of Twitter?

Start a blog. Publish until your heart’s content. Anyone with a phone, anywhere in the world, can read your Very Important Thoughts.

And these reasonable accommodations persist pretty far down the stack.

What if you are so odious that your blog’s web host kicks you off? You buy a box and set up your own server in your closet. It requires slightly more effort than putting a site on GoDaddy, but it’s neither expensive nor technically difficult. May I suggest the Hooli Box 3, Signature Edition? It’s a great value.

What if you’re trying to monetize your audience and you are such a deplorable that Stripe, PayPal, Square, Visa, and MasterCard refuse to serve you? How ever will you capture revenue? It’s impossible!

Oh, wait. It’s not. You can use bitcoin. Or you can just have your users mail you a check. Like everyone in the world did, for decades, until about 5 minutes ago.

In order to lose the ability to make reasonable accommodations you need to get all the way down to the level of ISP’s and banks refusing service.

3. Sierra On-Line, RIP

Finally, something fun.

Remember the early videogame designer Sierra On-Line? King’s Quest was their most popular game, but Leisure Suit Larry was—hands down—the company’s biggest cultural legacy. (Oh, the memories.) It turns out that the story of the company’s demise is pretty interesting. They were one of the top videogame publishers in America and they sold the company to a shadowy corporation which sold . . . coupons. And offered them a billion dollars. What could possibly go wrong?

On February 12, Williams negotiated with Forbes’ team an offer of a tax-free stock exchange, in which each share of Sierra stock would be exchanged for 1.225 shares of CUC stock; with CUC’s stock valued at approximately $48 per share, this represented a premium of about 69% over Sierra’s actual trading price. . . . Forbes boasted to Williams that CUC had “a long history” of “beating Wall Street expectations”; that its stock “consistently outperformed the market.”

It was an offer Williams couldn’t refuse; at least not back in 1996, when he did not know the reason CUC consistently outperformed the market and could offer a billion dollars for Sierra was because it made numbers up. . . .

“Nobody beats Wall Street estimates exactly by a penny 24 quarters in a row,” he remembers warning Williams of CUC. “That’s categorically impossible. Does not happen.”

Williams took the deal.