What Canada’s Euthanasia Advocates Ask Us to Believe

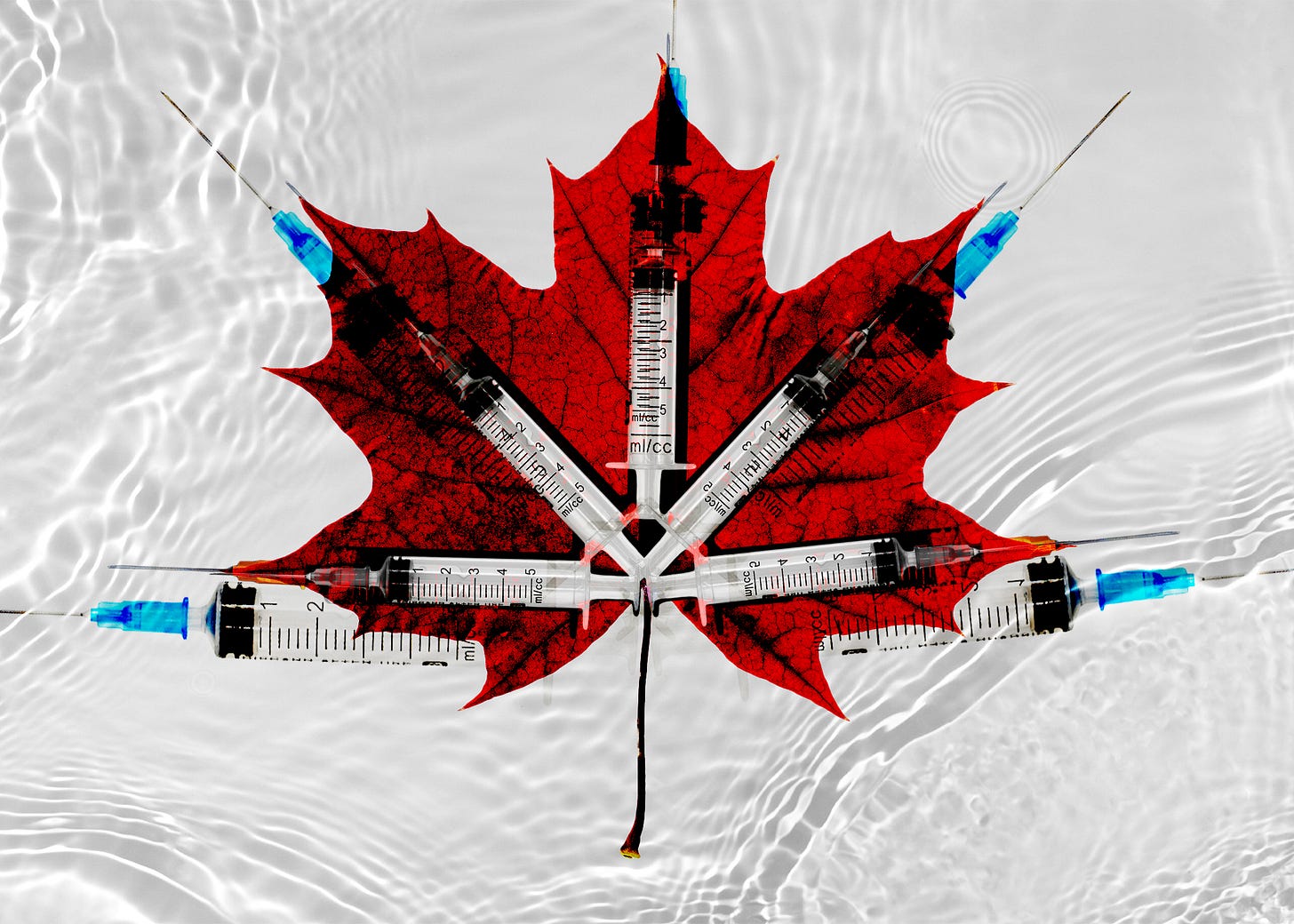

The country’s MAiD law will soon qualify those with only a mental health issue to opt for the procedure. It’s time to scrutinize the assumptions making these expansions possible.

AMERICANS TEND TO KNOW CURIOUSLY LITTLE about the extraordinary euthanasia regime that has recently emerged in Canada. The government calls it Medical Assistance in Dying, or MAiD—a sanitized acronym that evokes helpfulness and compassion. This certainly accords with the idealized picture of physician-assisted suicide, where a doctor provides drugs for a patient to end his or her own life, which is one of the practices allowed under Canadian MAiD regulations. But over 99 percent of MAiD cases in Canada—practically all of them—instead involve voluntary euthanasia, where the doctor administers the lethal drugs. Perhaps the government’s choice of a reality-obscuring euphemism is partly to blame for my compatriots’ hazy understanding of what is happening up north.

This inattention is why, when I bring the subject up to others in the States, I begin not by citing the complicated judicial and legislative history that led from Carter to Truchon to the passage of former bill C-7—I’ll cover that arc in a moment—but rather by stating its effects: MAiD, which has been legal in the country only since 2016, is already responsible for one in thirty deaths across Canada, and the number is as high as nearly one in twenty in some provinces. Those figures are from 2021; aggregated national data from last year should be released soon, and it is reasonable to expect these numbers to climb further: Advocates of MAiD tout increasing awareness and ease of access. In another context, these sorts of upticks could raise concerns about “suicidal contagion.”

The facts are startling, but even in Canada, they haven’t elicited any hesitation on the part of MAiD advocates, who have largely resisted attempts to slow down the expansion of its legal availability while failing to offer a robust intellectual defense of the new order. My aim in what follows is to summarize recent developments in Canada’s MAiD laws and then to scrutinize some commonly cited defenses of the country’s euthanasia regime.

Most euthanasia cases in Canada still fit the profile that advocacy groups like Dying with Dignity Canada have promoted to support the practice: A terminally ill patient, grievously suffering while awaiting a “reasonably foreseeable” death, wishes to hasten the end of his or her life by a few weeks or months. This type of case has informed the Canadian public’s understanding of MAiD since the muted debates that preceded its legalization. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada passed down its ruling in Carter v. Canada: The country’s Criminal Code would need to be revised to remove the prohibition on assisted dying because such prohibitions conflicted with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, specifically its protection of “the right to life, liberty, and security of the person.” The following year, legislation was passed that legalized MAiD and established a set of parameters for it. But following Truchon v. Attorney General of Canada, a 2019 case at the Superior Court of Québec that found no compelling reason to restrict euthanasia based on the “reasonable foreseeability of natural death”—a criterion built into the 2016 law—Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government acted to expand the law, introducing legislation at the end of 2020 to remove this limitation.

That bill, then known as C-7, passed in March 2021 and extended access to medical assistance in dying to non-terminal patients. (The then-pending bill’s features were discussed in detail in The Bulwark two years ago.) But the expansion of MAiD marches on. Provided nothing is done, suffering due to a mental health condition alone will soon qualify people to be killed by their doctors—a stipulation of former bill C-7, which called for the extension of MAiD to mental health patients after a delay of two years following the bill’s passage. Some psychiatrists and other mental health professionals have spoken up about the intolerable contradictions that arise in such cases, and the backlash has delayed the mental health provision’s implementation by another year to March 2024.

Not only is having a mental health issue on the verge of becoming a qualifying condition; advocacy groups are now calling for Canada to expand access to so-called “mature minors” who meet the government’s criteria for making their own decisions about their health. If the MAiD law is reformed again to make this further accommodation, suicidal teenagers seeking help could find themselves choosing between two sets of public resources: one intended to help them get through their crisis, and one intended to help them end it all. Trouble is already here: In 2021, fully one in six euthanasia recipients cited “isolation or loneliness” as one source of the suffering from which they sought permanent relief.

Jean Truchon, whose 2019 case led to the removal of the foreseeable death criterion from the MAiD law, is one such person. Though he had lived with the challenges of cerebral palsy, he cited the loneliness brought about by the pandemic as his motivation for pursuing MAiD. Doctors in Montreal helped him end his life in April 2020.

SINCE CANADA’S ORIGINAL MAID LAW was enacted in 2016, the staunchest critics of the practice and its legal expansion have been disability rights advocates, from grassroots organizations to international observers. Their fears—among others, that MAiD would come to be offered as a “solution” to the particular needs of a person with disabilities, especially if those needs are complicated or require costly interventions on the part of a province’s already strained single-payer system—have been confirmed by several widely reported cases since the law’s expansion beyond the terminally ill. Expressing despair due to poverty, lack of access to appropriate housing, or unmet needs for specialist medical care has been taken to be consistent with the provision of euthanasia. Indeed, some defenders of the regime have stated that it would be unjust to withhold euthanasia in such cases. To do so, they have argued, would be to render poverty an impediment to receiving medical care.

Journalists have made substantial efforts to describe the trajectory of the country’s euthanasia regime. Meagan Gillmore has extensively covered the rising chorus of criticism in the country for the Walrus, a Toronto-based magazine. For the New Atlantis, Alexander Raikin reported on the eager embrace of MAiD by Canada’s doctors and other medical providers; medical professionals’ positions on the issue often reflect those of CAMAP, a voluntary association that has acted as both an advocacy group for the expansion of euthanasia and as a standards agency for its provision. Many church leaders, especially mainline Protestants, have fallen in line with the government on the issue, too, as Benjamin Crosby wrote in an essay for Plough.

In spite of these and many other critical perspectives on the new reality of euthanasia in Canada, the momentum remains on the side of expansion. The Toronto Star’s Althia Raj conducted an interview late last year with justice minister and Attorney General of Canada David Lametti, who said that “I don’t think . . . that limiting access to MAiD is the solution” to the problem of people seeking it because of material insecurity and social issues, and further that “it would be horrific if we compounded the suffering” of some people who would “legitimately” seek MAiD by pursuing better safeguards that might delay their desired outcome. Lametti’s comments made clear that the Canadian government considers it more important to provide unfettered euthanasia access than the social and medical care that would stop Canadians who do not have terminal conditions from seeking to end their lives.

But for all the uniqueness of Canada’s situation—for example, although Canada and California have both legal provisions for MAiD and comparably sized populations, Canada recorded twenty times more deaths of this kind than California in 2021, as multiple writers have pointed out—the expansion of some version of assisted dying to ten states and the District of Columbia in recent years means that the questions raised by Canada’s euthanasia experiment are already live concerns for millions of Americans and will become increasingly relevant to millions more in the years to come.

THOSE QUESTIONS ARE COMPLEX: THEY demand self-scrutiny, especially on the part of those in power. This is why one of the most startling things about Canada’s MAiD regime is how thin the justifications of its expansions have been, and how little has been said or done to address substantive objections—not only those of religious critics who ground their positions in spiritual beliefs about the sanctity of life, but also of secular defenders of disability rights in Canada. These groups are demanding that the medical and political establishment live up to an ideal they no doubt espouse: that those who live with chronic conditions and disabilities have lives that are equally worth living, equally worth protecting and cherishing and celebrating, as those of their able-bodied compatriots.

Here, then, are three questionable claims about life, freedom, and MAiD that sustain Canada’s euthanasia regime—as well as those most similar to it in Belgium and the Netherlands—and that ought to be more thoroughly scrutinized for the sake of a more valuable public debate:

The right to life implies a right to die—and specifically, a right to die as and when one chooses.

Euthanasia is medical “care”—that is, care appropriately provided by doctors and other medical practitioners.

Limits on autonomy by the government are per se bad.

The first claim, that the right to life implies a right to die, lies at the heart of the judicial decisions in Carter and Truchon that brought about the legal framework for MAiD in Canada. The worry of the Supreme Court in Carter, for instance, was that preventing people from waiving their right to life would create an unduly burdensome duty to live. But the right to life isn’t something one can waive or not waive. Likewise, one cannot waive one’s right to bodily integrity or one’s right not to be tortured; all these rights are internally connected to the intrinsic wrongfulness of certain types of acts. Specifically, the right to life reflects the wrongfulness, in typical circumstances, of another person killing you. Moreover, even if making decisions about the end of one’s life is an important dimension of one’s agency, it simply does not follow that we can justly be euthanized, even with our consent. The right to life, in other words, does not imply a separate right to be killed by another. Such a right would need to be grounded independently— for instance, by arguing, as the philosopher Joel Feinberg tried to do in his 1977 Tanner Lecture on Human Values, that voluntary euthanasia is consistent with an unwaivable right to life—not simply asserted as an evident corollary of a core tenet of the human rights framework.

The second claim, that euthanasia is a legitimate form of medical care, undergirds MAiD’s recent expansion in Canada well beyond the terminally ill. Whether something counts as medical care is a complicated matter, and competing evaluative frameworks are inescapable. Even so, the active hastening of someone’s death, particularly when death would otherwise be remote, constitutes a plain inversion of traditional medical ethics centered on the precept to “first, do no harm.” Hence, such a practice must similarly be grounded as a legitimate act for doctors to perform rather than simply asserted to be one through its designation as “care.” The language of care can easily obscure the way that challenging end-of-life situations often require a complex balancing of interests and special safeguards to discourage medical practitioners—and medical systems—from collapsing challenging moral dilemmas into simple procedural decisions. Moreover, legitimate acts related to end-of-life care—the eschewal of certain extraordinary life-saving measures, for instance—are clearly distinguishable from more questionable ones such as euthanasia. Morally, it matters very much whether we are actively doing something or simply allowing it. The underlying moral issues, untouched by the strategic description of euthanasia as “care,” have led the American Medical Association to insist, in its Code of Medical Ethics, that euthanasia “is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer.”

The third claim, that limits on autonomy are bad in themselves, is essential to the case for the recent expansion of access to euthanasia, despite troubling evidence that some people are being offered—or are seeking—euthanasia because of social factors. For instance, two University of Toronto bioethicists have recently argued that, even if people cite social factors as the basis of their suffering, the state would be unduly limiting their autonomy by depriving them of access to euthanasia. Autonomy cannot be our sole value in the realm of medical treatment, especially when it is specified in such a thin way as to ignore the social and material conditions needed to exercise it. But even if limiting access to euthanasia is a limit on autonomy, we must hold on to the idea that a decent society simply does not allow people to do anything they like. That is so even when the state’s response to particular actions is therapeutic rather than punitive. The legitimate scope of state power extends beyond establishing a wide zone of autonomy for each person and ensuring they do not infringe on that of others, even in avowedly liberal democracies. Indeed, the state has special duties to protect the vulnerable, which means, in different stages of life, all of us. More generally, it is not entirely coherent to speak of a category of actions that pertain only to an isolated individual. What happens to one matters to us all; that is part of what it means to inhabit a society. But even more concretely, what happens to one person—especially death—is profoundly consequential (and can be extremely harmful) to that person’s loved ones, a fact that is urgently relevant to the moral and legal questions surrounding euthanasia, notwithstanding that fact’s near-invisibility in the context of the Canadian law governing the practice.

These criticisms of the arguments that have been employed to support Canada’s euthanasia regime are not meant to refute them; I hope rather to have shown that greater reflection on these problems is necessary. Slower, more careful thinking—and acting—can help to avert what some of the most vulnerable people in Canadian society are describing as a disaster for them.

More broadly, the example of Canada shows those of us who live in other liberal democratic and technocratic societies an important truth: that a slide toward moral oblivion in these matters is all too easy.