What In Conservatism Should Be Conserved?

And what must we change?

“If we want things to stay the same, things are going to have to change.” –Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, The Leopard

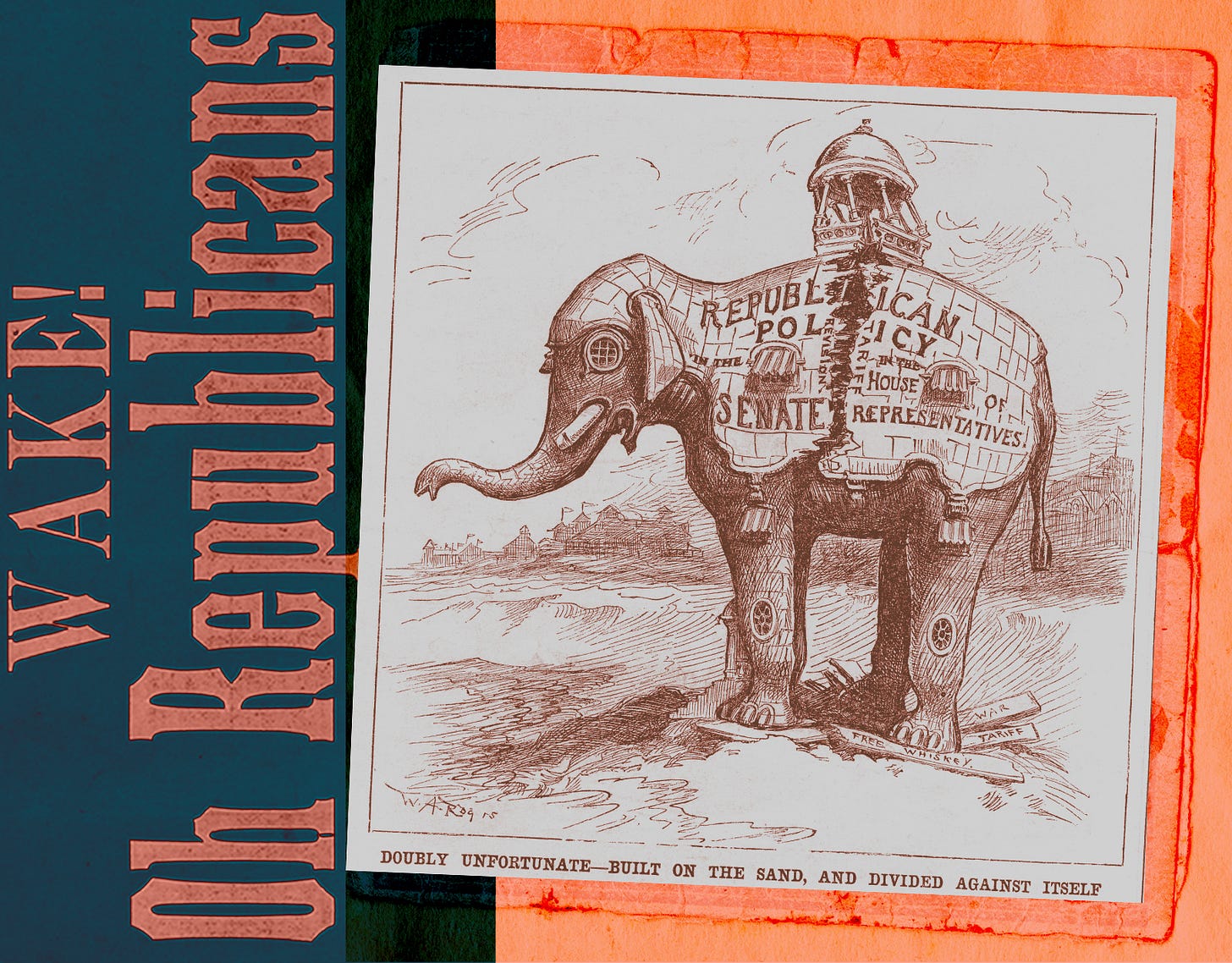

This Yogi Berra-esque quote from a dead Italian novelist is a longstanding conservative koan. Society is never static, and conservatives do not—or at least should not—want it to be. What conservatives should want is continuity: a sense that the society that they preserve, protect, and care for is the same one they looked after yesterday. Societies, like people, change—but they should not self-destruct. In a previous Bulwark article, we asked what was left to conserve about the United States, and offered some thoughts on what could form the basis of conservatism in the present era. We pick up here with an opposite question: What must we conserve about conservatism, and what must change? This is no mere academic exercise. Our cities are burning, our people are divided, our foreign policy is adrift, and our nation is literally sick. Some of the blame for these problems belongs to the left, but by no means all of it. For a two-party system like ours to function properly it must have a viable and healthy conservative party. America needs a governing consensus, so that it can know what is too much and what is not enough, what is on the table and what is not—and that implies having both a liberal or progressive party and a conservative party, and between them some sort of consensus about the boundaries of the policy debate. These failures of ideas and leadership were evident long before the 2016 election. While Donald Trump, as a candidate and as president, has been able to exploit the country’s polarization, it did not originate with him. Moreover, should he recede from the scene, it will be more, not less, necessary to attempt to make some sense of a chaotic Republican party. Doing so will require reassessing what about the old conservatism retains relevance and vitality. This is particularly topical, given the GOP’s recent decision not to make any changes to its 2016 platform at the 2020 Republican National Convention. In doing so, the party has allowed to stand policies it has already (for better or worse) repudiated, such as support for regime change in North Korea, as well as others that the general public has repudiated, such as gay conversion therapy. By failing to examine its own policies, the GOP has, in effect, decided to “let go and let Trump.” The Republican party retains some intellectuals, but if it continues to substitute a personality cult for a real program of governance, it will have fully forsaken the appellation bestowed upon it by Daniel Patrick Moynihan in 1980—a “party of ideas”—and truly become what liberals think it is: the “stupid party.” At a time when the United States could especially use a real conservative party, this behavior is unconscionable. To sort through the chaos, we offer here some thoughts on the future of American conservatism and the Republican party, broken into a series of questions that run through a range of options: What can’t we change? What shouldn’t we change? What could we change? What should we change? And finally: What must we change?

What Can’t We Change?

Let us begin (like good conservatives) by emphasizing continuity: articulating what must be conserved about conservatism. We are looking for its essence—its sine qua non; those principles without which American conservatism would cease to exist or become a monstrosity. Fundamental to American conservatism is the fusion of the classical liberalism of America’s founding and the basic social intuitions of conservatism. Neither one can stand on its own: America is not America without the liberalism of the Founders, and classical liberalism on the American right is protected, rather than undermined, by very basic conservative principles and instincts—such is the nature of conserving a liberal republic. In the application of these broad intuitions much variance can occur. The list that follows is not exhaustive, but an exhaustive list would include all these items.

Individual rights, limited government, the Constitution, and classical republicanism.

As we noted in our previous Bulwark article, borrowing from George F. Will, the ideological core of American conservatism has always been a belief that the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights, and the sentiments that produced them, are fundamentally good. This is so for classically liberal reasons (they form a complete, internally consistent and comprehensive system of political values) as well as for conservative reasons (a community cannot throw out its founding documents without profoundly harming itself). This basic understanding of America’s foundation and founding principles cannot be abandoned.

The difference in values between conservatives and their opponents has in recent history been characterized by the question of state expediency and individual independence. The government, in conservatives’ general understanding, represents individual citizens in areas that must be held in common, such as defense, law enforcement, foreign policy, adjudication of civil disputes, and perhaps in a limited fashion provides insurance against economic and environmental force majeure. It must be responsive to citizens’ concerns and serve their interests according to a social contract; it must not be understood as a separate body that disciplines its citizens and holds authority over them apart from what they appropriately delegate to it. American conservatives tend to understand government in Jeffersonian and Madisonian terms: It is there to guarantee individuals’ rights, including the fundamental rights enumerated in the Bill of Rights that ensure that the government will not become dangerous to its people. If respect for these rights means that some progressive goals are unattainable, then it is the goals, and not the rights, that must yield. This understanding of the social contract is too essential to conservatism for it ever to be given up. It is, in fact, too essential to America for it ever to be given up. For this reason, we anticipate that any future conservative movement or party would remain fundamentally pro-life and pro-Second Amendment, since these positions on these longstanding controversial issues are rooted in the Bill of Rights, classical republicanism, and classical liberalism. Some disagreement around the edges of these positions is to be anticipated, and a reinvigorated conservative movement would likely accept a wider range of views on these matters, as it did in the past. In basic terms, however, opposition to the state-sanctioned killing of unborn children and support for the right of self-defense would remain part of the conservative sensibility.

Respect for religion and a commitment to religious freedom.

Speaking of respect for rights, conservative respect for traditional religion must be retained. Institutional religion helps to order society and provides meaning and purpose to human life. And respect for individual religious practice, as long as it does not infringe others’ fundamental rights, is not only deeply engrained in our national self-understanding—as religious freedom was one of the motivators of the settlement of some of the American colonies—but also recognized in the First Amendment. Defense of religious freedom will always be on the short list of conservative principles.

Continuity.

This idea draws almost entirely on the classical conservative tradition. Conservatives have long believed in the connection of individuals to community and of present community to the past and future. They have in particular prized the idea of stewardship—the understanding that however much or little one has acquired from one’s forebears, one has the obligation to preserve those good things one has inherited and pass them on to ones descendants in at least as good condition as one received them (and, if this is not possible, to conserve what one can). This applies to laws and institutions, to wealth and prosperity, to one’s own and one’s family’s good name, and even to smaller traditions that define a community—as simple as a favorite holiday recipe, a treasured heirloom, or a communal ritual. Such things may be trivial, and the conservative value of prudence must counterbalance unreasonable zeal in the preservation of those things whose time has come and gone—but conservatives are right to understand that communities are sustained by the things they share in common and across time. The intuition that one’s country is becoming unrecognizable, though in need of careful reflection and appropriate application, is a valid expression of conservatives’ core sensibilities.

Prudence.

An essential conservative value that must carry forward is prudence—the humble recognition that caution must be exercised in handling major decisions, and that the more important the matter at hand, the more care must be applied. This does not mean never making a major change and cannot mean never making a major decision, but it does entail a sensibility that the greater the anticipated effect of a decision, and the more passion has entered into debate, the more care one should take in thinking about one’s position. As Chesterton famously suggested, you ought not to destroy a fence before you have learned why someone bothered to put it up. It does not mean one should never make a change (destroy the fence), but it does mean one should not rush into a change without considering the context and social fabric into which that change is woven. Under President Trump, conservatives have arguably become less prudent, following along with his disdain for institutions and abrupt and haphazard decision-making. Going forward, conservative prudence ought to be restored.

The pioneer spirit.

The story of American greatness includes settling a lawless frontier; braving hazards for a chance to believe and profess the dictates of conscience; crossing plains, mountains, and deserts in search of a new life; immigrating with few means to harsh cities in search of a mere chance at personal advancement; escaping slavery, fighting to end it, and then pushing for equality and advancement; starting businesses and inventing new technologies—and ultimately applying all of this to the defeat of great evils and the protection of the free world. These particularly American myths, whatever their inaccuracies and imperfections, inform the conservative ethos of independence, problem-solving, and participation in a great story of perseverance against all odds. Invoking these images is often unfashionable, but conservatives (who are supposed to look beyond fashion) have good reason to retain these myths and call upon their fellow citizens to exemplify them; they are the tropes of America’s national story, without which America cannot be conserved.

What Shouldn’t We Change?

This next category is less absolute—it refers to those conservative precepts that are not essential but are nevertheless important enough to be worth preserving.

Localism and federalism.

In principle, there is nothing in classical liberalism or conservatism that prescribes exactly how resource allocation and decision-making are to be handled by a republic, and although constitutional requirements must always be respected, the degree to which they are to be preserved and defended may vary. Nevertheless, the conservative movement will in the future likely continue to stick to its longstanding preference for respecting state and local authorities’ autonomy unless fundamental constitutional rights are being violated. The reason for defending localism and distributed governance in an era in which local matters are widely brought to national attention is exactly that: Not only do the needs of citizens in different communities vary, but any solution to the mob culture that we currently have, and that conservatives should abhor, will require a recommitment to “small-r” republicanism at state and local levels. In part, Americans retreated from republicanism as they accustomed themselves to passive acceptance of an order seemingly too big for them to manage, run by oligarchs of varying types. The recovery of American political sanity will require the recovery of a can-do mindset relative to governance, with citizens participating as voters and advocates rather than either passive subjects or irate protesters. This is best achieved in environments where votes count. The U.S. Congress, by contrast, is situated at a sort of sweet spot for dysfunction: There are just enough members of Congress to pass blame among themselves but not enough for any individual member to be responsive to, and be held accountable by, constituents. Pragmatism alone, to say nothing of ideology, will dictate that localized governance remain a plank in the conservative platform.

Basic fiscal conservatism.

Conservatives long believed—and conservative elected officials at least paid lip service to the belief—that taxpayer money is a public trust, to be spent wisely and, where possible, sparingly. In recent years, the Republican party has all but discarded this concern. But as federal debt continues to skyrocket—it now stands at about $26 trillion, double what it was a decade ago—it makes sense to return to the ideal of fiscal independence for taxpayers and not to pursue policies that further entrench them as permanent wards of the state.

What Could We Change?

At this level, we are moving from rigid essentialism to (gasp) policymaking. There is plenty of room here for new thinking—rather than just rehashing old disputes.

Platform absolutism.

Perhaps the biggest way in which conservatives could reconceptualize their movement is, to return to an older way of doing things: specifically, a bigger tent with more flexibility in exchange for greater buy-in. The basic problem here is that the party of federalism is becoming overcentralized. The Republican party is, of course, a federation of state parties that are, in turn, built on local parties. The national party’s platform is treated as a joke in some circles; it sometimes seems that its chief function is to provide opposition research on the party’s weirdest members. Nevertheless, there is a strong informal orthodoxy in the Republican party that proposes one-size-fits-all policy solutions and punishes independent action, an informal orthodoxy that has only grown in the era of Trump. This is not only inconsistent with the principle of localism described above, but is unrealistic and unproductive. The personality cult that surrounds Donald Trump is well known, and is what has allowed Trump to manipulate Republican lawmakers from Congress on down so effectively. But we would argue that Republican litmus testing and ideological puritanism is at once both older than Trump and also, comparatively speaking, quite recent. Prior to 2008, the Republican party was a big tent on a range of issues. Not only did it make compromises on abortion (Olympia Snowe, Susan Collins) and gun control (Rudy Giuliani) to win elections, but this big-tent attitude extended to other matters as well. Regionalism was common, with lawmakers working across the aisle for their states and areas of the country, and backroom dealing over fiscal small change kept the peace. Although the 1990s are often regarded as the harbinger of gridlock to come, including two government shutdowns, they were also a time in which basic governance got done, including aspects of policy that the congressional Republicans favored, such as welfare reform, and necessary compromises, such as on defense spending and balancing the budget. This minimally effective governance largely continued into the Bush era as well. This changed after the election of the Tea Party Congress in 2010, which effectively ended any sort of deal-making by ending earmarks, and whose operatives aggressively primaried moderate Republicans even when the winning Tea Party candidates were odds-on favorites to lose. In many cases, the products of this could only be described as weird (Sharron Angle, Christine O’Donnell), but even the relatively sane and normal senators and representatives were ideological purists, or were expected to toe policy lines given to them by purists. The Tea Party’s extremism and antics are not the point—the inability of the Republican party to move beyond them is. From 2010 onward, the Republican party was a parliamentary party in the British sense—despite being nominally decentralized, it hewed tightly, nationwide, to orthodoxy set by a relative handful of people, as long as the people in question satisfied the Tea Party’s litmus testing. During this time, the amount of legislation passed by Congress cratered, the percentage of times individual senators and representatives voted with their own party approached its theoretical limit, and the Republican party became famously obstructionist and uninterested in governance. It shut the government down and threatened to prevent the United States from servicing its debt. It is hard to doubt that this contributed, in a predictable vicious cycle, to the Republican siege mentality that ended in Trump’s nomination and election. It did not have to be this way, and in fact there was at least one notable case that went in the opposite direction: The Republican Senate conference scored a rare pick-up in 2010 when Scott Brown won a special election in Massachusetts. Though buoyed by Tea Party enthusiasm, Brown was a moderate Republican of the New England model, with a moderately pro-choice abortion position and a relatively left-wing position on gun control. His election was a welcome development for opponents of the Obamacare legislation then before Congress, but more to the point, it moved the needle very slightly in the direction of a return to the older model of a regionally distributed party. For ideological purists, Brown would have been no great success. But as a glass-half-full in a region from which the Republican party had been virtually extirpated, his election offered obvious benefits. This model can be copied—and in fact is being copied at present, with Republicans rallying around Susan Collins and her unapologetic willingness to put her state first. Such compromises to regional variation will have to continue if the Republican party is to rebuild from the siege mentality into which the Tea Party led it. After all, for conservatives the world is always going to hell in a handbasket—the question is simply how to salvage what one can. A model that might make sense for the future of the Republican party is that of the Scottish Tories, who are formally linked to the U.K. Conservative Party but who, on the long fight over Brexit, took their direction from their regional party leader Ruth Davidson instead of from Theresa May and her advisers. This was not ideal from a party unity standpoint, but it was better for all concerned: Scottish voters got a center-right option, and the Conservative Party got more seats. A Republican equivalent might involve an urban renaissance, with urban Republicans opposing Democrats while disavowing connections to Trumpism or to Republican national rhetoric that does not help them electorally. Alternatively, the divergence might be regional—something like this appears to be underway with centralized Republican support for Collins despite her heresies on issues such as abortion and her refusal to endorse Trump. Making this work would require pragmatism—conservatives might profess strong allegiance to core principles while being willing to accept 80 percent or even 51 percent orthodoxy in order to build a coalition. But it might be better than nothing, and there are aspects of conservative performance in various regions and demographics that suggest rock bottom has been reached and improvement might be easier than it seems.

Education policy?

We bring up education an example of an issue to which conservatives have given too little detailed thought. It can stand in for a host of other issues on which conservatives have shown a similar lack of serious policy thinking, and have failed to meet voters where they are. Whatever Republicans think about public education, and whatever policy proposals their think tanks generate for handling it, these obviously do not resonate enough with voters at the state and local levels to produce Republican policy successes. This no doubt contributes to the famous Republican inability to win elections in many urban areas. When it comes to education policy ideas that will attract voters, the suggestion box is mostly empty. It should not be. Possibly the most notorious cautionary tale in this area again stems from the Tea Party era. Post-2010, amidst a state fiscal crisis, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker famously took on the state’s teachers’ unions over pension bargaining rights. The reforms saved some money—at great cost in general acrimony and hard feelings that ultimately led to an attempted recall election—but no alternative vision for the state’s education system was proposed. Nor were Wisconsin Republicans in any great hurry to do anything about schools at the local level. (In fairness, the debate generated a few new ideas, such as holding schools to account for not meeting standards and relaxing teacher licensing requirements. But this short list may illustrate how limited the discussion actually was.) Conservatives are justified in their concern for the excessive bargaining power of public-employee unions. But they miss an opportunity if they enter policy debates solely to oppose and berate, and the case of education reform is probably an area in which they have been notorious for this of late. Something similar obtains at the national level in the slow-moving crisis of federal student loans. Famously understood as a financial protection racket that forces high school graduates to take out heavy debt to finance ever more expensive college education all so that they can compete with other students doing the same, the federal student loan program has saddled American students with an estimated $1.4 trillion in debt, more than doubling since 2008. The situation is untenable and calls for a long-term solution. The most that Republicans have offered of late has been complaints that college students are wealthier than average (partly true) and that colleges and universities have become postmodernist temples with declining educational standards (arguably true, but beside the point). Thus, all Republicans seem to offer is to complain about the problem. But talking points and policy are not the same things, and the basic problem—that attaining the American dream increasingly involves buying into a rigged game that wastes ungodly amounts of money and strangles opportunity—is thus left unsolved. More thinking is called for; it is not being done. There are many reasons Republicans have trouble winning elections in cities and among young people. But the refusal to deal with what is in front of them, as opposed to complaining about it, is probably near the top, and education policy is a perfect example of how this happens.

What Should We Change?

This brings us to a stronger imperative: What is going badly? While the list could include a wide range of issues, such as climate change, homeland security, the war on drugs, and matters relating to the family, we want to highlight two issues in particular need of reevaluation.

Policing.

In the short term it is appropriate to support necessary moves to keep violent protests from destroying property or escalating to shooting. But there remains the question of how to approach violent overreach by law enforcement. There is a crying need for conservatives to denounce and punish excessive force, not merely because of questions of racial justice, but because core constitutional freedoms and the fabric of our civil society depend on it. The perception that one’s neighbors approve of the state gunning down people in the street or selectively turning a blind eye to those who do is profoundly damaging to civic trust. Law and order and respecting rights ultimately cannot be extricated from each other.

Foreign policy.

For rethinking many of the issues related to foreign policy, the key is situational awareness. The unresponsiveness of the bipartisan foreign policy community (the dreaded “establishment” or “blob”) to voters’ needs and priorities, and the fecklessness of American military adventurism in the Middle East, fractured conservative unity and created an opening for Donald Trump. Lack of purpose on foreign policy is particularly troubling given the rise of China and Russia as great power competitors and the increased scarcity caused by the pandemic and recession. We will likely find ourselves increasingly pressured to do more to counter these emerging threats while there is less of everything—including domestic unity, political will, and material resources. American policy can always have as its goal the maintenance of a world friendly to democracy—but it must do so successfully and at acceptable cost in a world of increasing scarcity. Far too little thought has gone into how to do this, because nobody wants to seriously question the costs and benefits of American global leadership. Nor do they want to admit that the competition will be more challenging and complex.

What Must We Change?

And last, we now turn to those aspects of present conservatism that cannot be allowed to linger. Just as some aspects of the conservative movement are essential, others should never have been allowed in. We recognize that there were complex reasons for how conservatism found itself in this situation, but there are problems that need solving. In doing so, we are going to avoid any further mention of Donald Trump; it is more useful to point out what issues took a wrong turn rather than pin blame on a single individual. Whatever the outcome of the 2020 election, conservatives will have to rebuild their movement, and it is better to focus on what steps are necessary to take going forward than what has happened.

“It’s the economy stupid” redux.

We lead with this one in this section because it is so important. The country is in a truly dire situation. It must make painful choices about how to handle COVID-19 and how to manage the economic costs of doing so, and regardless, the level of economic hardship Americans are experiencing has few historical parallels apart from the Great Depression; relative to expectations, it is arguably worse. The country has over 10 percent unemployment and an economy that cratered at an annualized rate of 31 percent in the last quarter—in human terms, this has translated into families not paying rent for five months and in many cases going hungry. Many Americans are down to empty bank accounts, having gone into the crisis with barely a thousand dollars on average in savings. In the midst of all this, Congress went home rather than passing further unemployment benefits. This is shocking and unacceptable on face, but more so in light of the conservative tendency to stand firm on fiscal issues. In a “normal” recession (which this one isn’t), conservatives would likely find themselves standing athwart the road to serfdom yelling Stop, and they would define the problem as avoiding falling into socialism due to short-term risk aversion. Selling free-market economics in a recession is always difficult, but this one simply demands a different ethos. If Republicans and conservatives cannot meet voters where they are—including finding the money necessary to prevent starvation and mass eviction, they do not deserve to be in power. For the foreseeable future, moreover, conservatives are going to have to resist the economic purism that often informs their policy choices. Yes, in an ideal world tax and entitlement reform might lead to a better economy—but perfect has been the enemy of the good for some time with conservative fiscal policy, and right now it is the enemy of acceptability. (Conversely, if entitlement reform ever does end up on the agenda, it should be because some people need the money even more.) If tradeoffs between deficit spending and crisis management, and between long-term economic health and short-term disaster relief, are complex, this is a job for policy engineers.

Policy nihilism.

The lack of ideas and the seeming hostility to those who generate them are the biggest stumbling blocks for the current Republican party. While the energy of the Tea Party movement and the support for populist candidates may have been sufficient to win elections in the short term, such surges quickly burn out when it becomes obvious that they have no plan or coherent organizing principles other than simply opposing what their members do not like. Rather than being simply a reactionary ad hoc movement organized to resist, prudent conservatives should think carefully about how actually to govern. Republicans and conservatives are not wrong to note that credentialism and mindless adherence to experts is not only odd and cultish, but also breeds bad policy by essentially giving credentialed policy makers a free pass on the obligation to produce results that satisfy voters. Nor are they wrong to note that the policy establishment, both Democrat and Republican, has failed voters in myriad ways. Nevertheless, there is a difference between criticizing rot within elite circles and rejecting the necessity of ideas altogether. As the Cold War historian Philip Zelikow wrote recently, there was a time when American ingenuity was not only an unironic trope, but extended to policy making. In recent times, policy failures—in conception, in enactment, and in execution—have become so ubiquitous as to be unremarkable. Those who cite the existence of conservative think tanks as proof that conservatives take policy seriously are missing much of the picture: The think tanks are rarely heeded; even when they are, their proposals rarely meet voters where they are. As noted above, serious thought must be given to dealing with the situation as it is, not as one might wish it to be. Conservatives are going to have to rebuild their policy establishment, and do so around solutions that have a prayer of working out—both in the sense of being enacted and in the sense of doing something useful for a majority of average voters—in the current environment. Becoming an “idea party” again is a necessity for conservatives and Republicans if they hope to do more than survive.

Opposition for opposing’s sake.

Tribalism is the enemy of serious thought. We discussed the dangers of Manichean thinking in our previous Bulwark piece; it must go. The fact that public health and the Postal Service are being politicized is truly disturbing, as are the mindless conspiracy theories that fuel opposition to any good idea anywhere. The fact that it is increasingly difficult to imagine bipartisan legislation coming out of Congress speaks to this. As a thought experiment, could the Nunn-Lugar Act, the bipartisan 1991 bill that set up a program to safeguard ex-Soviet nuclear weapons, pass Congress today? One suspects not. As Rand Paul revealed in an unusually candid statement about police reform, the instant the Democrats support something, Republicans must oppose it. It is worth noting that Senator Richard Lugar, the coauthor of the legislation just mentioned, lost his primary bid for reelection in 2012 in large part because his fellow Republicans saw him as moderate and willing to work across the aisle. In this, conservatives of all factions, and the nation as a whole, are headed for a reckoning. Whatever policy one favors regarding COVID-19, it is indisputable that options for dealing with it were extremely limited by partisanship, which politicized every aspect of the response, from finger-pointing and Monday-morning quarterbacking over whether the pandemic could have been prevented, to arguments about tradeoffs between health and employment, to the trustworthiness or lack thereof of the public health community, to questions of what First Amendment protections were subject to restriction and which were sacrosanct, to questions about the effectiveness of masks. This made it nearly impossible to imagine compromise on more difficult issues such as a bridge-loan program to help businesses and extension of unemployment benefits. To be sure, many issues arising from this crisis involve painful tradeoffs and require sober discussion. It is tragic, however, that they had to become subjects of partisan signaling. The politics of the pandemic suggest a thought experiment: If it were possible to save 30 million people’s jobs, with no meaningful downside, by simply waving a magic wand—but one needed the other side’s approval and a political truce to do it, what would we do? What should we do? Whatever one’s answer, the issue is very trenchant. The pandemic and recession, not to mention the options they have created for great power adversaries working to crush the United States, militate against the kind of culture war in which Americans find themselves. What does that say about the state of things? What does it say about us? Whatever one’s answer, one has to look oneself in the mirror in the morning. To that end, if at all possible, conservatives must seek to de-escalate the culture war. Yes, rioting cannot be tolerated, abortion will remain an issue of conscience, assaults on constitutional freedoms must be met with resistance, there will be legitimate differences of opinion about how to handle the pandemic. However, responsible statecraft, to which conservatives should aspire, involves ensuring that such disputes are prevented from dominating the agenda. In the fragile state we are in, this argues for playing defense, not offense, even at the cost of not having everything; it also argues for negotiation and compromise. Exactly how to do this is a question we cannot answer. We are reasonably certain that at this point in the culture war, the issues are not really the issue. If it were simply a case of gun control and abortion driving animosity, congressional leaders could find a way to call a truce, perhaps allowing precedents to stand or making other, similar assurances. All aspects of the current culture war suggest this is not the case. Joe Biden’s moderate political positions are irrelevant to the right’s perception of him as an agent of destructive anarchists. Denunciations of violence have not stopped it, and justifications for cultural antagonism have shifted. What the culture war is about has shifted at an alarming pace. Early this year, COVID-19 denialism replaced climate change denialism as the focus of left-wing hostility; subsequently racism was declared more important than COVID-19; in the course of protests against it, goalposts were shifted and in some cases realigned, with dealing with police brutality giving way to calls for abolishing the police, then attacks on statues and historiography, then maximalist attacks on systemic racism and defenses of property violence. On the right, the discourse shifted in parallel from condemnation of cancel culture to condemnation of property destruction. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that those who want to fight are finding excuses to do so, particularly amid a social environment filled with anger, anxiety, and boredom. Left-wing and right-wing extremists appear essentially leaderless. They can be buoyed by Trumpian demagoguery or sympathetic media, but this is not their sole driving force, and their stated motives and justifications shift. Paradoxically, the fight is not as much about promoting a coherent ideology as it is about resisting the other side. This tribalism for tribalism’s sake exacerbates the potential for a downward spiral: Just as right-wing fears of left-wing extremism drove Trump’s rise, and just as opposition to Trump’s violent demagoguery drove the Never Trumpers to oppose him, so too it is possible that opposition to left-wing excesses will drive moderates and center-leftists into opposition—and perhaps into Trump’s arms. It is up to conservatives as much as anyone to do their part to arrest this. And this will be more difficult because whereas policing conservatives’ own side in 2016 amounted to shifting leftward, Never Trump conservatives currently in coalition with those to the left of them will increasingly be policing the left, not the right (to which they are now opposed), even as pro-Trump conservatives show as little sign of wanting to rein in Trump now as in 2016. Perhaps all one can do is not contribute further to the mess. There is no easy solution here, but conservatives, who value stability, ought to avoid destabilizing their own country where and how they can. If we can get to a point where some compromises are possible regarding the older cultural issues, we will know we have made progress in pushing back against the pernicious political tribalism. For now, though, every patriotic American citizen has a moral obligation to look for a way out.

Identity politics / white nationalism / Christian identitarianism.

To that end, we turn to the culture war’s battlefield du jour. Race is a toxic subject, yet it is something the Republican party and conservatism more broadly are going to have to grapple with. Conservatives can and should reject the racialization of discourse that “wokism” represents while simultaneously broadening their coalition beyond the current stereotype of mostly white, middle-aged homeowners. Rather than simply oppose the distasteful elements of wokism, conservatives would be better served by emphasizing that classical liberalism and the principle of equality before the law apply to all regardless of their background. This should go without saying, but conservatives should reject extremist views on race and religion as a matter of first principle. Not only are white nationalism and Christian identitarianism abhorrent and un-American, but they also harm the best chance conservatism has of rebuilding itself. Uniting classical liberals will require a recommitment not only to unifying rhetoric, but for this nation to actually “rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.” The 2016 association of conservatism with the alt-right, and now the dead albatross of armed right-wing militant protesters showing up across the country, have continued to tarnish the conservative movement’s image. These were the kind of associations that conservatives historically shunned, and their ascendancy has been a severe blow to the conservative movement’s legitimacy. The RNC’s foregrounding of Senator Tim Scott, not merely as an African-American senator but also as a (rare) example of someone who has gotten something useful done under the current administration, was a step in the right direction. So is rhetoric calling for disciplining errant police officers and thus reaffirming that constitutional rights do in fact belong to all citizens equally. More of this will be necessary, but this is the direction that must be taken.

Immigration.

The great choice for conservatives may well be between their core values and tribal allegiances, and questions of immigration raise precisely this point. We are agnostic on what should be done on immigration issues, because they are neither simple nor even connected—concern over violations of immigration law, over the possibility of importing foreign conflicts and terrorism, and over competition for scarce jobs are all distinct and complex issues. What we do argue, however, is that anyone serious about conserving the United States as a classically liberal republic with some conservative cultural elements cannot afford to alienate whole demographics who represent, in many cases, the best of the virtues conservatives hold dear. In simple terms, if one values America, one should not cold-shoulder or dehumanize people who have put much on the line to come to this country. If one values the Constitution and its freedoms, treating those who hope to enjoy them with suspicion and harassment does no one any good. If one values entrepreneurship, one should praise immigrants, who probably represent it more than most. If one values traditional religion, alienating communities who tend to take their religion seriously is, to misquote a famous Frenchman, “worse than a crime; it is a mistake.” Debates around immigration tend to arise at times when there is a lot of it and when the frictions it generates are more acutely felt—i.e., in times of economic stagnation. The current rancor surrounding immigration mirrors that seen at the turn of the twentieth century. Then as now, the foreign-born fraction of the U.S. population was historically high; then as now, the U.S. economy was stagnant and crisis-prone. In such an environment, not only is there more than the usual amount of ethnic tension, but the policy fixes that might ameliorate it are less available than usual because of economic stagnation, and the competition it generates is more keenly felt. People are, quite simply, less likely to shrug off wage competition with people who are not like them when there is less of everything to go around. All this we accept, and this has to be confronted. As noted, a key component of any movement or party right now should be getting the economy moving again, and it is a proper job for policy intellectuals to consider how that might be done. But conservatives would do better to placate their nativist wing by offering them solutions to their problems rather than by hostility to immigrants who not infrequently share the same values conservatives ultimately want to promote.

Putting It Together

We can leave off, then, on that note. The problems of conservatism are not its fundamental ideas, but inflexibility in their application, lack of realism, and a catastrophic failure of coalition-building even when ideology offers a playbook for doing so. What must we keep? Our values. What must we change? Our hypocrisy and fecklessness in living out those values. What is arguable? Everything in between—in particular, how to generate the ideas that will actually deliver something to the voters that will make it all worthwhile.