What Nobel Prizes Say About National Greatness

The excellence of a few is a source of pride for us all.

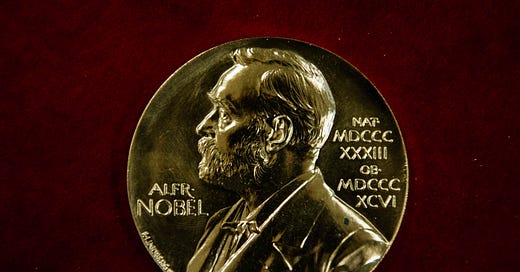

It’s Nobel prize season. The just-announced 2021 winners in medicine/physiology are two Americans, David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian, who’ve done groundbreaking research on the senses of touch, taste, heat, and pain. Their joint discoveries may yield new, non-opioid treatments for pain and other breakthroughs. Dr. Patapoutian had his cell phone switched off and so missed the call from Stockholm. The committee eventually reached his 94-year-old father on a landline, so Dr. Patapoutian learned that he hit the prestige jackpot from his dad.

Do you feel a flush of pride when Americans win Nobel prizes? I do. It’s a sign that for all of our division, disarray, and decay we continue to achieve excellence. If you peruse the winners of Nobel prizes by country since 1901, you find that a number of European countries are well-represented. France has earned 70, Germany 109, and Great Britain 133. Russia/Soviet Union claimed 31, and Belgium 11. But towering over the list is the USA with 388.

This year’s winners in medicine are not atypical. One is native-born and the other an immigrant. Dr. Patapoutian, who traces his ancestors to Armenia, was born in Beirut. He and his brother fled the civil war there when he was 18. He worked odd jobs including delivering pizzas and writing horoscopes for an Armenian newspaper to establish residency in California so that he could attend college. While at UCLA, he found a job in a lab hoping that it would help him gain admission to medical school. It changed his life. He fell in love with basic research.

Everyone knows, or thinks they know, that our universities are plagued by group think and wokeness. But those smothering fashions mostly skip the hard sciences, where a combination of investment in basic research, rigorous standards, and a long tradition of academic freedom create the conditions for talent to thrive and discoveries to bloom. By the way, China has earned 8 Nobel prizes.

Our openness to immigrants is part of the story too. Since the prizes began at the start of the 20th century, immigrants have accounted for 37 percent of American winners in the hard sciences. Immigrants have been well-represented among American winners in other fields as well. In 2019, two of the three U.S. winners in economics were immigrants—Abhijit Banerjee, born in India, and Esther Duflo, born in France. At least one American winner of the Nobel prize for literature, poet Czeslaw Milosz, was born in Poland, and Peace prize winner Henry Kissinger was born in Germany.

That talented people of all sorts (including those with little education) yearn to come here remains one of our greatest strengths. It’s not that Americans are smarter or harder working than other people; it’s that our culture and institutions support excellence. As Dr. Patapoutian reflected, “In Lebanon, I didn’t even know about scientists as a career.”

But there are movements in America now to limit or even eliminate programs for the gifted and talented. In New York, a task force appointed by Mayor Bill De Blasio recommended abolishing all of the city’s gifted programs and selective high schools. Seattle’s system of testing children in early grades to identify “highly capable” learners has come under fire. And in northern Virginia, the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology (TJ) has changed its admission criteria to be more inclusive.

There is always a tension in democracies between excellence and egalitarianism. The gap between subgroups in school performance gives rise to calls to change standards so that the representation of each group in elite institutions can more accurately reflect the group’s percentage of the population.

TJ, a magnet school renowned for its superior math and science curriculum, is close to where my children grew up. They were eligible to apply, but weren’t STEM oriented, so they took a pass. But other families, especially immigrants from Asia, regarded admission to TJ as the holy grail—a public high school that could be a ticket to the best colleges—and their kids studied hard to secure one of those valuable slots.

TJ’s admission test led to student enrollments that were not reflective of the ethnic groupings in the region. Fairfax County’s overall student body is 38 percent white, 27 percent Hispanic, 20 percent Asian, and 10 percent Black. In the 2019-2020 school year, enrollment at TJ was 71.5 percent Asian, 19.48 percent non-Hispanic white, 2.6 percent Hispanic or Latino, 1.72 percent Black, and 4.70 percent other.

The new admission criteria adopted for the 2021-2022 school year eliminated the standardized test, raised the required grade point average, and allocated slots in the freshman class for the top 1.5 percent of students from each middle school. It also eliminated the $100 application fee.

A group of Asian students is suing Fairfax County, arguing that the change is motivated by racial discrimination. Their suit alleges that the greatest losers in the new system will be Asian students and greatest winners will be whites.

So far, the new system does seem to have disadvantaged Asian students. Their share of the class dropped to 54.36. The number of Black students increased from 1.7 to 7.09. Hispanics were boosted to 11.27, and whites increased their representation to 22.36.

Is that just? The previous system did not discriminate on any basis except academic talent. Now it will discriminate on other grounds for the sake of diversity.

Teasing apart why some ethnic groups perform better in school than others is extremely difficult. Culture, family structure, historical discrimination, and luck all play roles. But there are two ways to attempt to make society more egalitarian. One is to drag down the top and the other is to raise up the bottom.

Fairfax County’s decision to eliminate the $100 application fee seems to be an excellent way to remove a barrier for poorer families. Lowering standards at TJ, on the other hand, elevates diversity at the expense of excellence.

The STEM-centric education at TJ isn’t for every student, but it does serve society at large. The kind of students who are capable of advanced math and science work go on to make discoveries that help the rest of us live better lives. It should be there for the future Dr. Patapoutians.