What Tim Walz Tells Us About Kamala and the Future of Liberalism

About that VP pick . . .

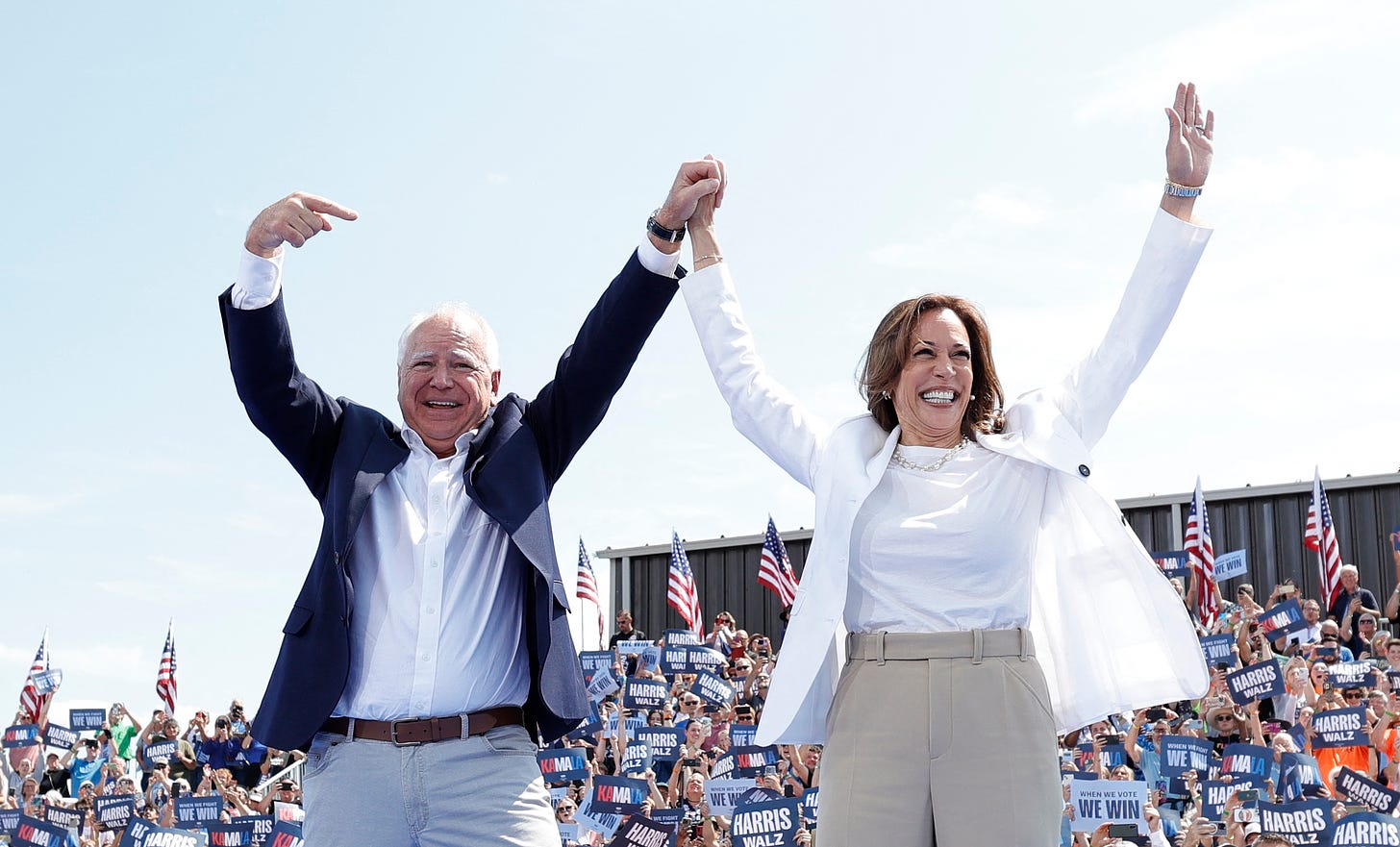

1. Draft Day

Two weeks ago I made the case that picking Tim Walz over Josh Shapiro would be the political version of drafting D-Wade over LeBron in 2003. After the Walz selection was announced, a buddy texted me that I had the wrong sport. This was an NFL pick:

You know when a guy goes three rounds too high in the NFL draft because he has a great combine but doesn't really know how to play football? That's what Walz feels like.

My buddy has a point.

There’s a lot to like about Walz as a political commodity and a running mate. Sample list:

He’s an everyman.

He’s not a lawyer.

He codes as white-working class, what with the teaching, and the hunting, and the football coaching.

But also there are question marks:

How complete was his vetting, really? On such a short timeline the full proctological exam wasn’t going to be possible for any candidate, which is probably why the attempt to Swift Boat Walz caught the campaign by surprise. The Harris campaign has to hope there’s nothing else in his background to become a distraction.

You can’t be both an everyman and a rock star. Harris now has to provide 95 percent of the starpower for the ticket.

He’s progressive—more on this in a moment—meaning that his presence doesn’t blunt attacks against Harris as being too progressive for swing voters.

In short: There are reasons to be hopeful that Walz works out. But if Harris loses Pennsylvania by 10,000 votes . . . yikes.

At the moment, however, I’m more interested in what the pick tells us about Kamala Harris and the future of the Democratic party.

Let’s take them one at a time.

As I wrote a few weeks ago, we have no idea what sort of president Kamala Harris would be. Maybe she’d be a good one. Maybe she’d be a bad one. For our purposes, all that matters is that she’s committed to democracy. That’s enough.

Picking Walz is Harris’s first presidential decision and it’s a Rorschach. I could tell you a story where Harris choosing Walz is a sign of her wisdom and practicality. Alternately, I can tell you a story where it’s an indication of her weakness. Let me spin it for you both ways:

(1) While Josh Shapiro was the obvious best choice,1 the Democratic party is a large coalition and the progressive members of the coalition really didn’t want Shapiro. The progressives aren’t a plurality, but they’re an important constituency.

Faced with the reality of progressive antipathy toward Shapiro, Harris pivoted. She recognized that she needed to put aside value judgments and acknowledge the flat reality that picking Shapiro would create some dissent. She was hard-headed enough to understand that any dissent from inside her coalition could blunt her momentum.

So Harris was wise and adaptable. She took this reality and rolled with it. She moved on to Walz—a pick who would not antagonize any parts of the Democratic coalition and also might (a) help with working-class whites while (b) placating progressives enough to give her room to move toward the center on other vectors.

(2) The other way of looking at Harris’s decision is that she caved. She was clearly close to picking Shapiro. Part of the progressive left freaked out and made their displeasure known. So Harris backed down and went with the progressive darling instead.

In this version of the story, Harris acted not out of wisdom but conflict avoidance and she demonstrated that she can be bullied by the progressive wing of the Democratic coalition.

Obviously, the first view suggests habits of mind that might make Harris a good president. The second view . . . less so.

I’d be interested in which version of the story you think is closest to the truth. Maybe there’s a third one I haven’t considered?

2. Progressives

Some Never Trump-types were disappointed in the Walz pick. They wanted Shapiro. But that’s life inside a coalition. You don’t always get what you want.

What interests me is the type of progressive Tim Walz is and what that could mean for the Democratic party.

When people say “progressive” they tend to think of either (1) CaliforniaLand big-government liberalism, or (2) Campus radical identitarianism.

Walz doesn’t come from either of those schools.