What’s the Deal With JD Vance and Kids?

There’s something strange about the way the GOP vice presidential candidate talks about his family.

JD VANCE HAS ONCE AGAIN SAID something cringe about children. In this case, his own.

In a recent interview with the New York Times, the Ohio Republican answered a number of questions about faith and family with uncomfortable candor.

Asked about his conversion to Catholicism, he discussed meritocracy, his search for how to live a virtuous life, and appealing to the authority of his wife’s opinion: “She was, like, really into it. Meaning, she thought that thinking about the question of converting and getting baptized and becoming a Christian, she thought that they were good for me, in sort of a good-for-your-soul kind of way.”

Had she converted, the interviewer asked? “No, she hasn’t,” Vance said, laughing. “That’s why I feel bad about it. She’s got three kids. Obviously, I help with the kids, but because I’m kind of the one going to church, she feels more responsibility to keep the kids quiet in the church.”

It’s not quite as bad in context as the subsequent internet pile-on would suggest (“she” has three kids???). But there was something strange about it.

When Vance said he’s the one “going” to church, what he meant is that he is the one participating in the great spiritual mystery of the liturgy and holy obligation; his family, meanwhile, is just there, trying not to disturb him. The way he describes it, JD and Usha Vance are caught in a mirror of shame, he asking her to give up her Sundays to meet the demands of his faith, and she wanting to maintain dignity and not let the kids cause embarrassment. It is all deeply Catholic, I’ll give him that.

The interviewer, Lulu Garcia-Navarro, pressed Vance on his conversion, pointing to the dysfunction of his childhood home and asking him if part of the allure of the church is the emphasis on the nuclear family. Bingo. “The American dream to me was never making a lot of money, buying a big house, driving a fast car. It was having what me and Usha have right now,” Vance replied.

There is something pat about this answer. But there was another tension point Garcia-Navarro wanted to press on: How Vance’s “family values” beliefs informed his mockery of childless cat ladies as “sociopathic,” “psychotic,” and “deranged.”

Vance insisted that these were “dumb comments” expressed an idea in a “very inarticulate way.” But the problem in trying to shrug off those comments is found in a credo Vance himself may have heard in the pews: “From the fullness of the heart, the mouth speaks” (Matthew 12:34 and Luke 6:45).

Was it really just a half-baked thought he expressed sarcastically multiple times in a variety of settings?

Vance portrayed himself as the victim of a (willful?) misunderstanding: All the talk about “cat ladies” is a distraction from the core of his argument, he stressed, in one of the interview’s tense moments. “I’m talking about the political sensibility that’s very anti-child. . . . We have become anti-family in this country.”

THE ISSUE OF “FAMILY” HAS BEEN CENTRAL to this election, with debates raging over when and how a woman can decide to start one, to the costs it takes to feed and support one. It’s a debate that Vance and likeminded Republicans and figures on the New Right believe undergird their political success. But what does family actually mean to Vance?

Before he was a senator, he wrote Hillbilly Elegy, his bestselling memoir detailing the difficulties of his own upbringing as the son of a single mother suffering from drug addiction, and describing his sense of doom that he’d not be able to escape his downtrodden origins. But in interviews like the one in the Times, he provides additional insights into how he personally views the family.

He shared with Garcia-Navarro an anecdote of a young woman on a train handling her unruly children. The misbehaving children were “complete disasters,” he said. The mother “was being so patient” with them but everyone around her was apparently “so angry” and staring—but Vance sympathized with the mother.

I’ve had similar experiences riding with my own kids on various modes of public transportation, and again it just sort of hit me like, okay, this is really, really bad. I do think that there’s this pathological frustration with children that just is a new thing in American society. I think it’s very dark.

Though he might see a darkness to the “pathological frustration” that Americans have with children, the truth is Vance himself routinely exhibits it.

Back in August, he recounted telling his 7-year-old son to “shut the hell up” while he was getting the call from Trump asking him to be his running mate. At a rally in September, he quipped that his younger son was probably off looking for a building to burn as a “chaos agent.” At another rally last week, he made more derogatory remarks about his children: “I’m surprised we made it this whole time without anyone really complaining. Maybe I can trade you my kids, you could knock some sense into them.”

Taken alone, each example could be excused as a daft, poorly delivered, but innocuous and even sad little attempt to be relatable (except for maybe “knock some sense into them”). But together, it’s a pattern—perhaps candid, but also off-putting and even disturbing—that clicks together like a puzzle piece with his natalist rhetoric.

SO MUCH OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY is projection, impotence, and a desire to control women: They bear the children and then must manage those “disasters.” As weird as JD Vance’s fixation on women and children may seem, it is in keeping with the GOP platform. It’s a feature, not a bug.

“The senator represents a strain of reactionary anti-feminism among the very online right that has, in recent years, seeped into the Republican mainstream,” Helen Lewis wrote for the Atlantic earlier this month.

For decades, one of the major knocks against the anti-abortion right has been that they seem to care about fetuses being protected up until the baby is actually born. They have no meaningful plans to address the cost of healthcare, the cost of housing, and the cost of childcare—the obstacles that lead many young women to feel like they don’t have a choice. And what plans they do have are usually narrowly crafted to benefit only those who align with Vance’s vision of what constitutes a “family.”

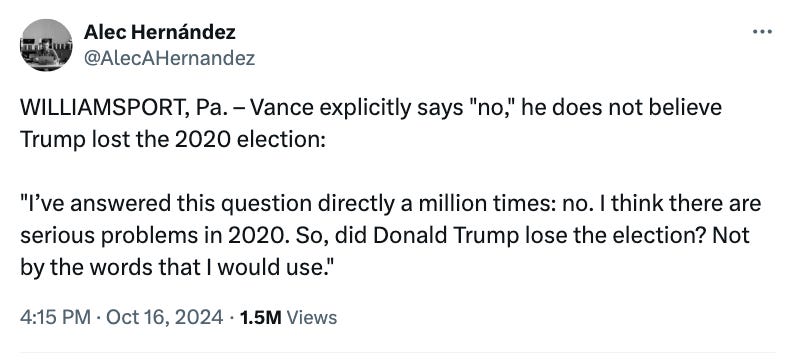

At the end of their interview, Garcia-Navarro asked Vance the most important questions facing our democracy: Did Donald Trump lose the 2020 election, would he have certified the election in 2020, and will he commit to a peaceful transfer of power in 2024? Vance, frustrated, tried to avoid answering directly. Later, on the campaign trail, he was less guarded, or maybe just more worn down. NBCNews reported when faced with the question again he answered “no” explicitly:

Vance’s stance brings to mind the closing couplet Louise Glück wrote in her poem “Nostos”:

“We look at the world once, in childhood. / The rest is memory.”

We can see the shadow Vance’s childhood casts on his life from his willingness to contort himself to appease powerful men who promise him safety from scarcity. What will his wife’s children remember?