No TNB tonight! We did this week’s show on Tuesday.

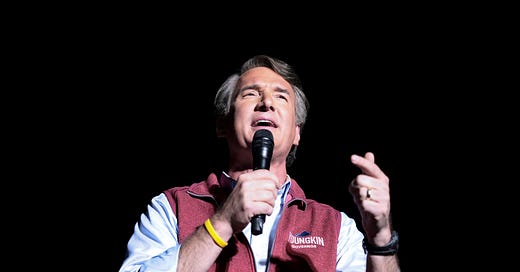

1. Why Not Youngkin?

Yesterday I got an email from an unhappy reader who wanted to know how I could possibly object to Glenn Youngkin. Isn’t Youngkin a positive development? Isn’t he obviously not-crazy? Isn’t he a sign of green shoots for our post-Trump future?

These are good questions and it’s worth unpacking them. So let’s go.

(1) The health of the Republican party is the most important political issue of our time.

Democracy doesn’t work with only one healthy political party. You need two of them, otherwise every election becomes a crisis point.

What do I mean by “healthy”? How about this: The party’s commitment to the democratic process can be taken as given.

If you want to play for more, you could add a couple other qualifications: That the party exists within a perception of reality that is more or less shared by the general public. That the party is not principally driven by grievance.

But honestly, those are probably nice-to-haves. The bedrock is simply a commitment to democracy and the rule of law so basic that it isn’t worth talking about. And the Republican party as it exists today—both in the composition of a large number of its elected officials and the views of a large percentage of its voting members—does not meet that benchmark.

So no matter who you are and what your political preferences are, the return of the GOP to this baseline level of health is vitally important for you.

(2) Glenn Youngkin is healthier than Donald Trump.

That’s just a fact. Youngkin exists in the real world. He has at least a normal level of cognitive function. Whatever you think of Youngkin as a politician, you probably wouldn’t think twice about letting him watch your kids while you ran to the grocery store.

And his politics exist on a recognizable plane of reality—driven by electoral convenience, but within the spectrum of American political norms.

Further, there is no indication that Youngkin has authoritarian impulses of his own. Had Youngkin lost the election on Tuesday, it is very hard to see him calling on the Proud Boys to stand by, or organizing a rally in Richmond with the intention of overturning the result.

Maybe his response to defeat would not have been as normal as Terry McAuliffe’s. But then again, maybe it would have been. Glenn Youngkin is not an aspiring Mussolini.

(3) So why not Youngkin? What makes him dangerous?

All politicians tell lies. It’s part of the job. Donald Trump was never going to build The Wall. Joe Biden was never going to create a public option. Overpromising and underdelivering is a normal—if regrettable—feature of American politics.

What marked Youngkin as still being part of the sickness that has infected the Republican party was his refusal to admit to basic, irrefutable facts concerning the 2020 election. These were not matters of opinion or preference, but raw facts of life. Donald Trump lost the 2020 election. By quite a lot. The election was free and fair. Period. The end.

Glenn Youngkin danced around this fact for a very long time. Then he tried to finesse it. Then he backed away from it again.

What this revealed was that Youngkin was not willing to say that 2+2=4. And that if his voters demanded that he pretend that 2+2=🍌, then he would do it.

This reveals a dangerous lack of commitment to those bedrock commitments on democracy and the rule of law. Not because Youngkin himself would want to throw them over—but because if his voters demanded such a thing of him, he might roll over and give them what they want.

Put it this way: Pretend it’s 2024 and Joe Biden has won Virginia by 500 votes over Donald Trump. Now pretend that Youngkin’s voters demand he do something about it: refuse to certify, “find” 501 votes, work with the legislature to appoint an alternate slate of electors, etc.

What is your confidence level that Youngkin would refuse?

Maybe it’s high. Certainly, it would be higher than if Amanda Chase were the governor.

But based on his refusal to testify to the truth of 2020, there’s no reasonable way to be at 100 percent.

The problem with Youngkin is that while he, personally, may be pro-democracy, a substantial portion of his voters are not. And he has demonstrated that he is their hostage.

(4) But what are the odds that Youngkin ever has to make a call like that?

Pretty slim. The most likely scenario is that Youngkin will be a perfectly normal governor in Virginia and that the functional difference between his administration and a McAuliffe administration will be small.

It’s also highly unlikely that Virginia will be a tipping point state in 2024.

But we no longer live in a country where the peaceful transfer of power is assured and the commitment to democracy and the rule of law is assumed.

And until we return to such a place, then electing even Good Republicans is a risk if they are unwilling to stand up to their more authoritarian supporters.

2. Uncuck Newsmax

It’s awful how our corporate media overlords are always silencing the brave truth tellers.

3. The Real French Dispatch

I saw Wes Anderson’s love letter to the New Yorker yesterday and it reminded me how fantastic America’s chief magazine of letters is. There are 30 or 40 pieces that are stuck in my brain that I want to share with you, but the magazine’s website is almost comically awful. So instead, I’ll share this John McPhee appreciation of Mr. Shawn:

Soon after the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was passed, in 1971, which resulted in the reorganization of Alaskan land on a vast and complex scale, I developed a strong desire to go there, stay there, and write about the state in its transition. When I asked William Shawn, The New Yorker’s editor, if he would approve and underwrite the project, his response was firm and negative. Why? Not because it was an unworthy subject, not because The New Yorker was over budget, but because he didn’t want to read about any place that cold. He had a similar reaction to Newfoundland (“Um, uh, well, uh, is it cold there?”). Newfoundland, like Florida, is more than a thousand miles below the Arctic Circle, but Mr. Shawn shivered at the thought of it. I never went to work in Newfoundland, but, like slowly dripping water, I kept mentioning Alaska until at last I was in Chicago boarding Northwest 3. . . .

So I have no idea by what freakishness of inattention Mr. Shawn had approved my application, a few years earlier, to go around rural Georgia with a woman who collected, and in many cases ate, animals dead on the road. She actually had several agendas, foremost of which was that she—Carol Ruckdeschel—and her colleague Sam Candler in the Georgia Natural Areas Council were covering the state in quest of wild acreages that might be preserved before it was too late. Under this ecological fog, Mr. Shawn seems not to have noticed the dead animals, let alone thought of them as anybody’s food, but I was acutely conscious from Day One of the journey and Day One of the writing that my first and perhaps only reader was going to be William Shawn. It shaped the structure, let me tell you. . . .

I turned in the manuscript and went for a five-day walk in my own living room. The phone rang.

“Hello.”

“Hello, Mr. McPhee. How are you?” He spoke in a very light, very low, and rather lilting voice, not a weak voice, but diffident to a spectacular extent for a man we called the iron mouse.

“Fine, thank you, Mr. Shawn. How are you?”

“Fine, thank you. Is this a good time to be calling?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Well, I liked your story . . . No. I didn’t like your story. I could hardly read it. But that woman is closer to the earth than I am. Her work is significant. I’m pleased to publish it.”

Read the whole thing. And if you have a love for magazines of ideas, then go see The French Dispatch.