When Historians Complain About Movies

There are lessons in all the griping and sniping over Ridley Scott’s ‘Napoleon.’

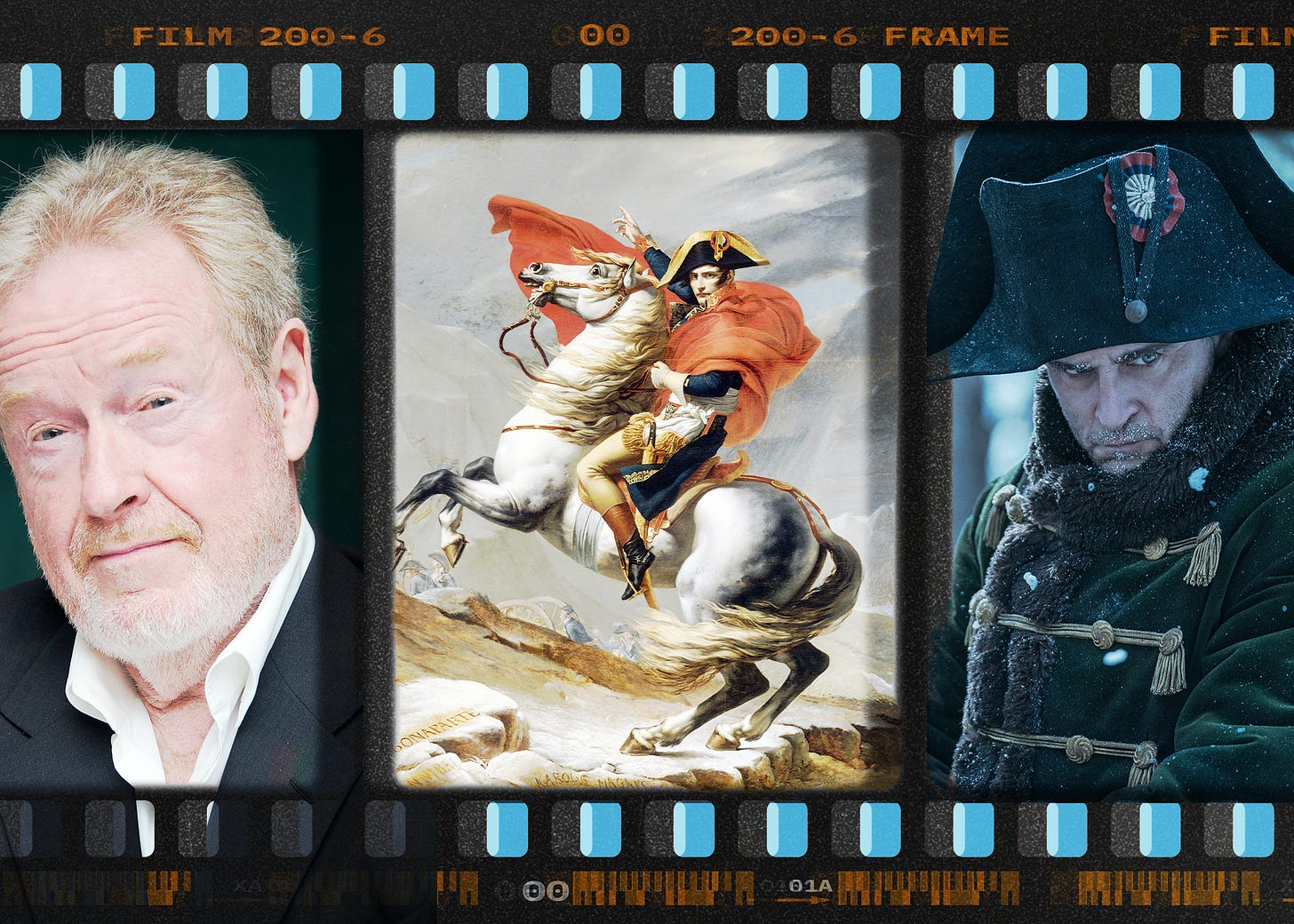

“GET A LIFE!” THAT’S HOW RIDLEY SCOTT, out promoting his new epic Napoleon, responded to criticism of the movie’s historical accuracy. Scott was triggered by a TikTok video from British pop historian and documentary maker Dan Snow pointing out problems such as the emperor’s supposedly humble origins (he was a nobleman’s son); Marie Antoinette’s wild mane as she went to the guillotine (her hair was cropped short that day); Napoleon’s witnessing her execution (he was in southern France when it happened, not Paris); French troops cannonading a pyramid (the only ones at the Battle of the Pyramids were in the name); and Napoleon leading cavalry charges (the commander wouldn’t do that).

Scott bristles when journalists ask about the real history behind the movie. “Were you there?” he boasts of asking historians. “No? Well, shut the f*** up.”

The director’s insults won’t persuade anyone, but there’s an important point about historians’ critiques of history movies hiding in his petulance. Saying “that’s not how it happened” is easily dismissed. Worse, it misses an opportunity for historians to use the tools of our discipline to do what we want to do most: teach others about the past.

There’s a venerable type of history exam question called the “identification,” in which students are asked to describe a person or event, such as, say, the Napoleonic Code, and explain its significance. That’s the right technique for highlighting historical inaccuracies on the big screen. So the Marie Antoinette character has the wrong hairstyle for her execution—why does it matter? If it’s just an incorrect detail, overlook it. If it does make a difference, explain what the difference is.

This is what Alyssa Rosenberg, in the Bulwark podcast Across the Movie Aisle this week, described as the difference between inaccuracy of detail and inaccuracy of narrative. If depicting fictitious moments helps Scott tell a basically true story about Napoleon, that’s defensible artistic license. If Scott were to depict Napoleon winning Waterloo not as an alternate history but as fact, that would be altogether different. Historians were more amused than annoyed when Quentin Tarantino depicted Hitler’s premature demise at the hands of a Jewish-American assassination squad in Inglorious Basterds; it seems unfitting that Scott should be pilloried for far more minor factual infractions.

Of course, details matter, and enough inaccuracies of detail do create an inaccurate narrative. The historian Estelle Paranque, for example explained that Scott’s portrayal of Marie Antoinette as “fearless and a bit feisty” is wrong for the execution scene because by the end of her life, the queen was “extremely sad and vulnerable.”

The object of many years of abuse, much of it pornographic, Marie Antoinette was crushed by the accusation of incest coerced from her youngest son by revolutionaries. Paranque’s commentary reveals the stakes in getting the scene right. It’s more than “her hair should be shorter.” It’s about who the often-caricatured queen really was.

Just as historians are usually good at explaining historical context, they excel at considering questions of genre and audience when analyzing sources. That’s another tool to build better history movie criticism. At one level, movies and works of history are just different.

STILL, IT MAY BE HELPFUL to think a bit more about how artistic license works and how far it extends.

Napoleon watching the queen’s execution, leading cavalry charges, and shooting a chunk out of a pyramid are all dramatic, as Dan Snow notes in his video. But the deviations from fact go beyond needing to entertain. In a movie called Napoleon, the Little Corporal has to be in the middle of everything.

Otherwise, the story is too hard to comprehend. As an audience to a performance in a visual medium, we know what we can see, not so much what we’re told. No one wants to have Napoleon read a letter about the execution or survey the battlefield while getting detailed reports from his lieutenants about how the horsemen are doing. That’s not cinematic: It would be not just boring but cognitively taxing to watch. Scott apparently sensed this in using the pyramid bombardment as a shorthand. “I don’t know if [Napoleon] did that,” the director conceded in an interview. “But it was a fast way of saying he took Egypt.”

Now, maybe a filmmaker’s artistic choices don’t work. It’s tough to balance realism, which an audience wants in a history movie, and intelligibility, which audiences also need. It’s often worth arguing over the tradeoffs involved—and merely saying “it didn’t happen like that” short-circuits a deeper understanding of both history writing and movie making.

LURKING BENEATH HISTORIANS’ CRITICISM of Napoleon and Hollywood’s history-related blockbusters in general is a feeling of helplessness—a sense that we’re badly outgunned. A movie by a big-name director, no matter how flawed, will influence more people than any history class, no matter how skillfully it’s taught. Against a movie with a $200 million budget, an overworked professor at a regional state college doesn’t stand a chance. Film beats history class every time.

I used to feel this way, too, but now I’m more sanguine. In grad school fifteen years ago, I assumed I’d devote a lot of my teaching to unravelling myths from popular culture and complicating lessons learned in school. Now, when K–12 history is so often shunted aside for STEM and standardized testing, more and more students come into my courses with only the vaguest ideas about what I used to think were the basics, including an awareness that there was a French guy called Napoleon who tried to conquer Europe in the early nineteenth century. I could once count on students remembering something about the Louisiana Purchase’s connection to Napoleon’s ambitions, the disaster in Russia paralleling the German offensive in WWII, and the Battle of Waterloo being a synonym for defeat.

No longer. Maybe the funny hat and the hand-in-coat pose spark a memory. I can’t count on much more, at least not as generally shared baseline knowledge. It’s a serious problem. I can deal with misconceptions. But no conception of the past? I don’t know what to do with that.

I’ll take the new Napoleon, warts and all, and teach from it, as I’ve done for years with clips from Scott’s previous epic, Gladiator. It dates me to show a movie from 2000, but it works. Students are savvy about visual culture and enjoy seeing what’s real, what’s invented, and why it matters.

Ridley Scott doesn’t have to be so defensive about his movies. Historians don’t have to point out every flaw as if cataloguing inaccuracies is enough. No, historians don’t need to get a life. They just need to elevate their movie criticism.

David Head is an associate lecturer of history at the University of Central Florida and distinguished faculty fellow in history at Kentucky Wesleyan College. He is co-editor of A Republic of Scoundrels: The Schemers, Intriguers, and Adventurers Who Created a New American Nation, forthcoming next month from Pegasus. Twitter: @davidheadphd.