Who Were the Americans Who Fought on D-Day?

A new exhibition seeks to understand the young soldiers who came ashore at Normandy.

The Dawn of the American Century (1919–1944): Under the Red, White, and Blue

Mémorial de Caen, France

through May 1, 2025

IN BLEAK TIMES, HOPE COMES from unexpected places. In this case, from France—a country with a penchant for fatalism more than optimism.

Enter Kléber Arhoul. The chief executive of the Mémorial de Caen and general curator of its new exhibition, The Dawn of the American Century (1919–1944), Arhoul waxed eloquent enough in our recent interview that I had a surprising desire to wave an American flag around the Normandy museum’s window-lined, high-ceilinged café where we met. I wanted to gather up the Americans among that day’s museum visitors and tell them not to give up hope. We’ve been here before! All is not lost! At least that’s what Arhoul says about us.

Given that a bleak outlook is one of the few things Americans of all political persuasions seem to share these days, a few rays of sunshine from gray northern France are not just refreshing but inspiring.

Arhoul has an infectious passion for the story of American life in the years between the world wars. He recounted with exuberance his journey around the United States last fall as he searched out items to borrow from various American institutions.

Part of what first attracted me to the exhibition was the thought of marking D-Day’s eightieth anniversary by exploring my native country’s history through the eyes of my adopted country. I’ve lived in France for over a decade, but this is the first big D-Day anniversary since I took up residence in Normandy.

And this is the last big anniversary for which we’ll have significant numbers of firsthand participants, veterans and civilians alike, present to lend gravity to the speeches delivered by heads of state.

But while the speeches and international media coverage—both of which are largely presented by people who drop into Normandy just for a couple days—serve important roles, they can unintentionally obscure the small-scale humanity of what transpired here eighty years ago.

For me, D-Day is no longer just an important international event from the past. It’s now a local event that marked my community then and still marks my everyday life in tangible ways. A bike ride through the birdsong-filled Orne River estuary takes me past graffitied German bunkers.

A friendly “bonjour” to a local on a walk turns into stories of his other summer strolls on the wooded path from his family beach home past the American Cemetery on the edge of the sea in Colleville-sur-Mer. He and his wife refer to it as a garden and say June 6 commemoration events are emotionally moving even if they snarl traffic for a week on tiny country roads.

My Uber driver tells me proudly how it’s still a family event to put flowers on the grave of his great-grandfather who was among the 177 French commandos who fought ashore on D-Day. Great-grandpa died liberating the community his family lived in then and lives in now.

The reflection of world historical events on this type of normal life frames the Mémorial’s exhibition. Rather than speaking of their deaths, Arhoul and the museum’s scientific curator, Clément Fabre, wanted to explore the lives of D-Day’s soldiers.

THE DAWN OF THE AMERICAN CENTURY BEGINS WITH A QUESTION: Where did the American soldiers who gave their lives on the beaches of Normandy in the early morning of June 6, 1944, come from? What cultural forces shaped them before they found themselves facing Omaha Beach’s impossible cliffs?

“You’re not born a soldier,” Arhoul says. “You become one. But before becoming a soldier, you’re a citizen, a child, a teenager, a young adult.”

The two and a half decades between the return of America’s victorious soldiers from one world war and the commitment to send troops back to Europe for round two were full of significant cultural change.

Silent films became talkies. Black and white became color. Jazz came into its own. California surfing culture gained prominence. The automobile industry contributed to economic prosperity. Monopoly was born.

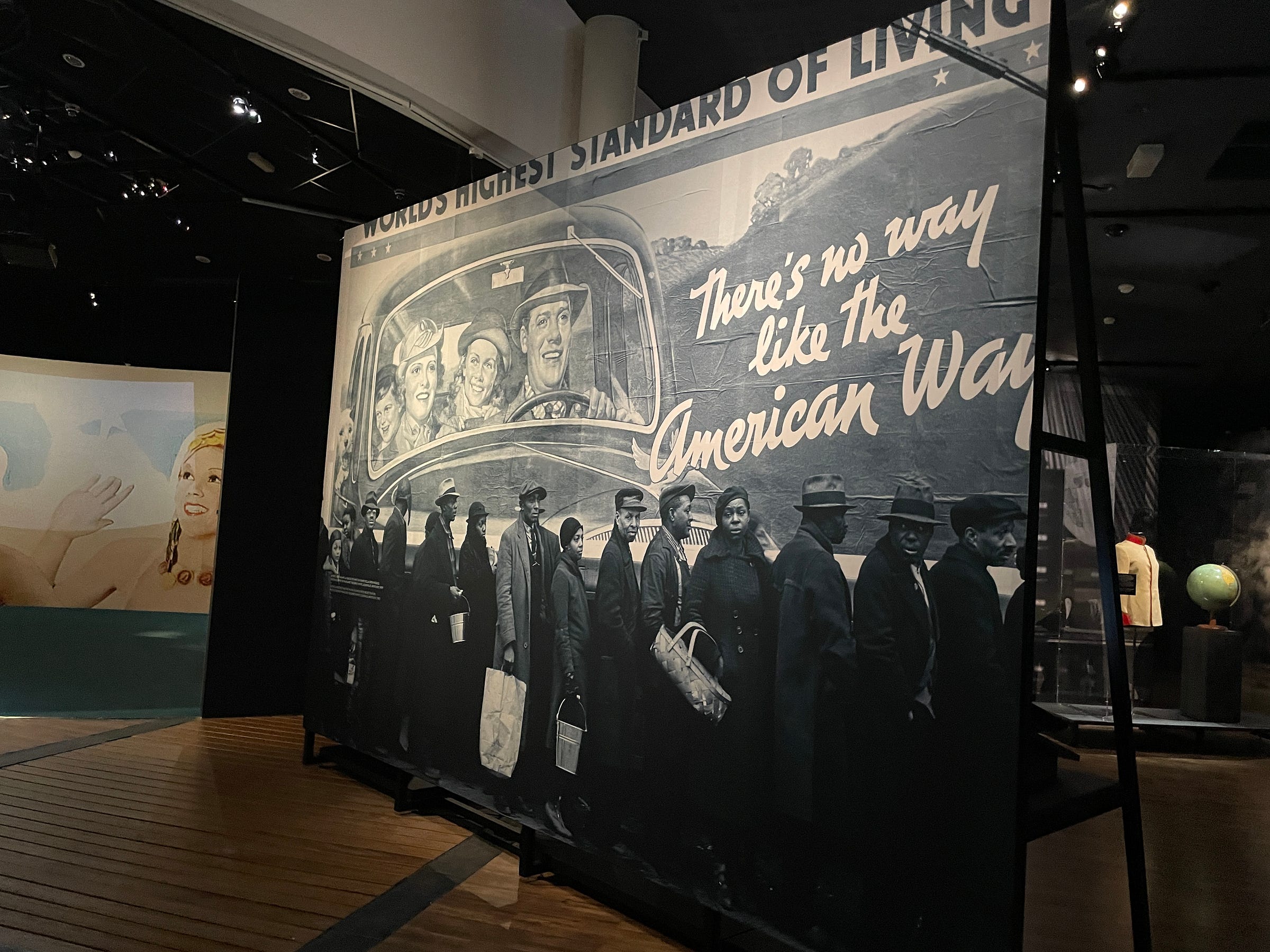

But this period also saw the apex of the second Ku Klux Klan, the Tulsa race massacre, and murders of the Osage in Oklahoma. And then came the Wall Street crash of 1929, the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl.

All these are represented in the exhibition—often in huge, blown-up photographs visitors walk past—as is the turn toward Roosevelt and recovery. As a press release from the museum notes, “In the space of one decade, a nation broken by the Great Depression found in itself the resources to eventually establish itself as leader of the Free World.”

In this exhibition, Arhoul says, we see an America tempted by isolationism—tempted not to look at the world but to look inward. Yet just as America had shaken off isolationism and entered the First World War, Roosevelt worked to counter isolationism as war broke out again in Europe. The isolationist temptation ended with the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the United States took up its responsibility as an emerging world power, ultimately bringing its troops to Normandy’s shores.

“We show that America has many faces, so we need to get away from caricature, and this exhibition helps us understand the diversity and complexity of America,” says Arhoul.

THE EXHIBITION, TOO, HAS MANY FACES. Alongside key objects borrowed from American institutions—the Smithsonian, Princeton University, the FDR Presidential Library and Museum, the National Steinbeck Center, and more—are videos in which curators from these institutions address visitors.

“It was really important for us to design this exhibition with two voices, two points of view,” said Fabre during the press event for the exhibit:

to have both our viewpoint, the French viewpoint, the French historian’s viewpoint, on this history, but also to have the American viewpoint on this history. We found it to be a really nice way of commemorating the sacrifice of the soldiers of June 6 to tell this story in two voices, this story that concerns us all because of their sacrifice.

Randall Thropp, a costume and prop archivist for Paramount Pictures, came in person to the exhibition’s May opening and noted how happy Paramount, Warner Bros., and “all of us in that little Hollywood archive community” were to contribute to this project. But his involvement goes beyond that.

When a Hollywood meeting with Arhoul and Fabre wrapped up and the partnerships were taking form, Thropp asked them if they would be interested in the collection of photos from the first half of the twentieth century that he’d been amassing since adolescence. The Frenchmen jumped at the offer.

Thus, forty-five images from Thropp’s personal collection are featured in the exhibition, the first time these images collected from flea markets, estate sale shoe boxes, eBay, and antique stores have been shown publicly. Taken by everyday Americans, they offer windows into the lives of American GIs before they became soldiers.

Thropp says he’s lucky when he finds pictures that have notations on the back. Most of the images’ details are a mystery. “We don’t know how many of these guys actually came home,” he says. “The photograph of the fellow hugging his mother—did he make it back home? We don’t know.”

And here we can return to Arhoul’s pep rally, a call to remember who everyday Americans have been again and again in the face of an unknown future, great challenges, and requests to stand with their allies.

Through this collection of objects and videos, audio clips from presidential speeches, war propaganda, and jewelry worn by famous actresses, Arhoul says, in words that lose some of their French poetry when translated to English,

What we’re showing is that when America is in crisis and in difficulty, it is capable of digging deep within itself to find the conditions for a rebound. Every time it’s been in crisis, America has bounced back, and this is the thing that is the strength of this country, which has always looked ahead and not back.

Punctuating words for effect while he speaks, Arhoul says it’s this American ability to look ahead that fascinates Europeans—in particular France, with its longstanding friendship with the United States, dating back to Lafayette.

“We’re very attentive to what’s happening in the United States today, but our job is not to predict the future . . . nor to judge,” he says. “Rather, our job is to say where it comes from: It has a glorious past, a magnificent past, an extraordinarily resilient people, and when those people stand by their country’s diversity and its plurality, they make it a great country, a great power.”