Whole Worlds in a Moment

With bright colors and bold shapes, the paintings of Pierre Bonnard find spectacle even in stillness.

Bonnard’s Worlds

Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

through June 2, 2024

AN EYE-POPPING NEW EXHIBITION in Washington captures the scenes and moments of everyday life that inspired the French painter Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947). “Bonnard’s Worlds” invites us to walk along the Parisian boulevards that sparked his creativity, visit the sumptuous gardens he created in Provence, and even sneak peeks into the intimate domestic spaces he shared with his muse, longtime companion, and eventual wife, Marthe.

Born near Paris, Pierre Bonnard grew up in the capital city and in southeastern France. His family sent him to study law, but Bonnard detoured to make art his career. Along with Paul Gauguin and Édouard Vuillard, he was a founding member in 1888 of les Nabis (“the prophets”), a group of young artists who believed that color and shape could represent experience. Their movement marked a departure from the Impressionism that had dominated French art since the epochal 1874 exhibition organized by Degas, Monet, Renoir, Cezanne, Morisot, and others. (Of note: The Musée d’Orsay is opening a major exhibition later this month to celebrate the 150th anniversary of that legendary exhibition; it will come to Washington in the fall.) But Bonnard developed his own particular style, and his paintings, as the new exhibition demonstrates, are marked by a unique passion for intense color and radiated light.

“Bonnard’s Worlds” has sixty paintings from all periods of his career. Because every work the artist created was inspired by what he saw in his everyday life, the exhibition is organized not chronologically but around places. Exhibition viewers are transported from Parisian street scenes, to Bonnard’s gardens, to quiet domestic spaces, to windows and doors that connect his interior and exterior worlds.

The beginning galleries focus on the street scenes, when the young artist would patrol the Parisian pavement looking for subjects. After decades of disruption, the city was flourishing by 1889 when the Exposition Universelle opened to honor the centenary of the French Revolution. A giant world’s fair, the Exposition drew over 32 million visitors, including 2 million alone eager to see the controversial new Eiffel Tower.

Bonnard immersed himself in the city’s liveliness, sketching and making notes as he walked the boulevards. He would later paint from memory, reconstructing and reimagining the scenes he had observed. As curator Isabelle Cahn writes in the exhibition catalogue, Bonnard’s “slightly naïve style expressed in all simplicity the idea of a democratic republic where working men, housewives, and soldiers could all mingle in the public space.”

In paintings like Paris, Rue de Parme on Bastille Day (1890), Bonnard happily mixed “children and dogs, bare-headed errand boys . . . carriages driven by ancient coachmen in yellow overcoats, wheelbarrows and trucks with green and red wheels, a wagon full of flowers,” and on and on, as critic Paul Jamot noted in 1906. These compositions were created by “the most sensitive eye and the wittiest brush . . . with a joy that retains all the spontaneity of the object seen.”

From the street scenes, “Bonnard’s Worlds” next journeys to the landscapes and gardens that filled the artist’s life in Provence and Normandy. As Cyrille Sciama, director of the Musée des Impressionnismes in Giverny writes in the catalogue, it was in Normandy that Bonnard developed “his own singular and unique style,” executing “works vibrant in color and of a new density.”

Bonnard was enthusiastic about his gardens, wanting them to be wild and “full of fantasy,” Sciama writes. The Terrace (1918) depicts a free-flowing garden very unlike Monet’s at Giverny, known for its carefully curated swathes of color. Bonnard’s passion for the color yellow is cheered in Bouquet of Mimosas (1945), and in Women with a Dog (1891) he uses the garden as a gathering place for family, friends, and a menagerie of dogs, cats, and rabbits.

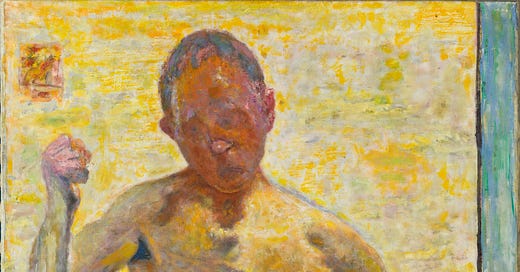

He was inspired by the landscapes he saw around him, as conveyed in such paintings as The Riviera (1923), The Palm (1926), and Steep Path at Le Cannet (1945). Sometimes his eye was caught simply by stepping outside his house, or perhaps when walking in the surrounding hills. Did the sunlight hit something that got his attention, or was there a spark of color hidden in the bracken?

Another favorite Bonnard trope was to use windows and doors to connect the interior and exterior parts of his life. The Artist’s Studio (1900) and Studio with Mimosa, Le Cannet (1939–46) exemplify how he used windows, doors, and mirrors to frame “pictures within pictures” in his paintings.

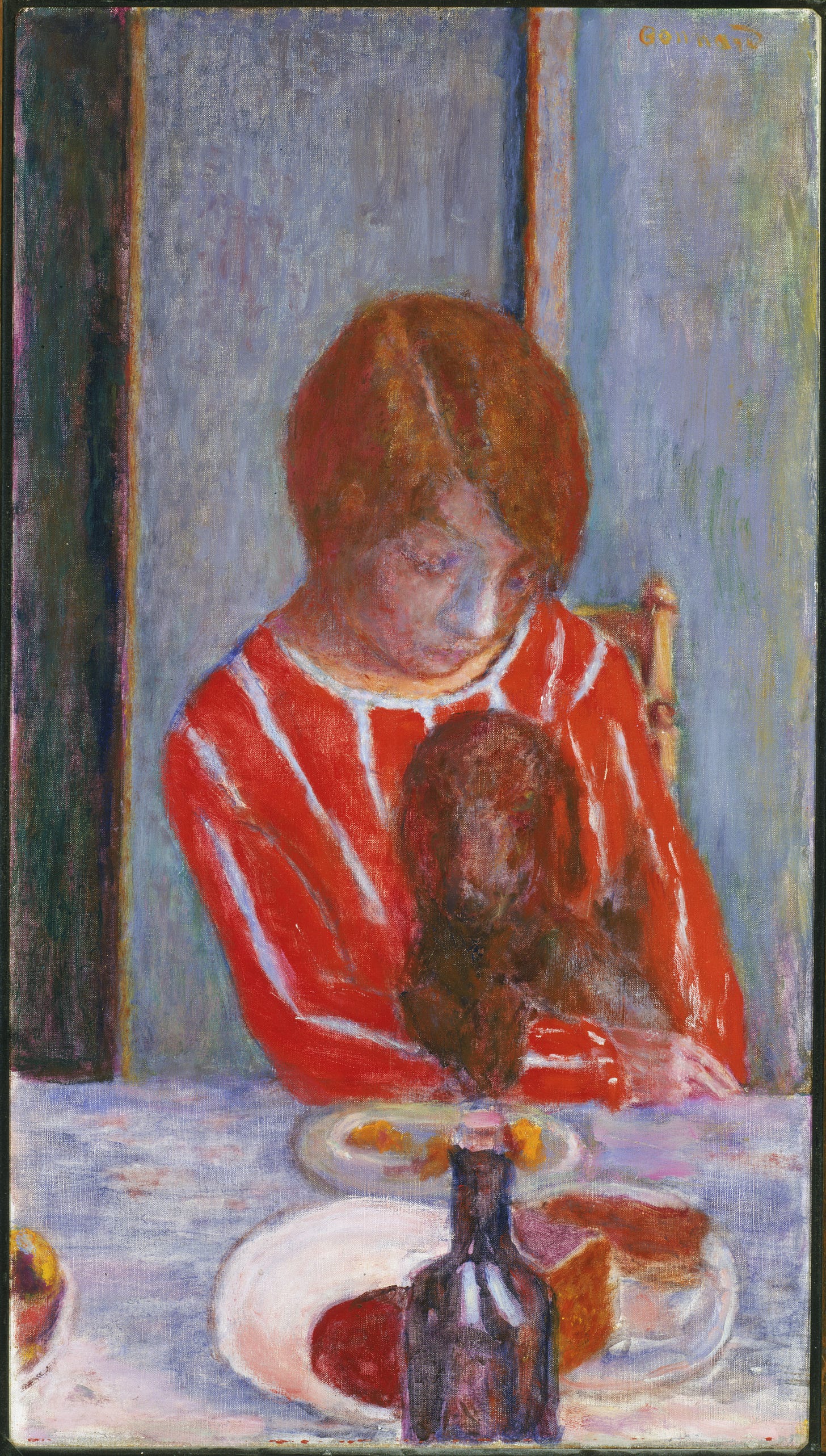

Dogs—notably one of the family dachshunds—and cats occasionally appear in his paintings. In Coffee (1915), one of the dachshunds is placed on the edge of the table near Marthe, while Woman with Dog (1922) shows Marthe cradling a dog in her lap. In The Work Table (1926), there is a cacophony of colors painted across the table, while a sofa behind the table harbors a white cat and a sleeping dachshund.

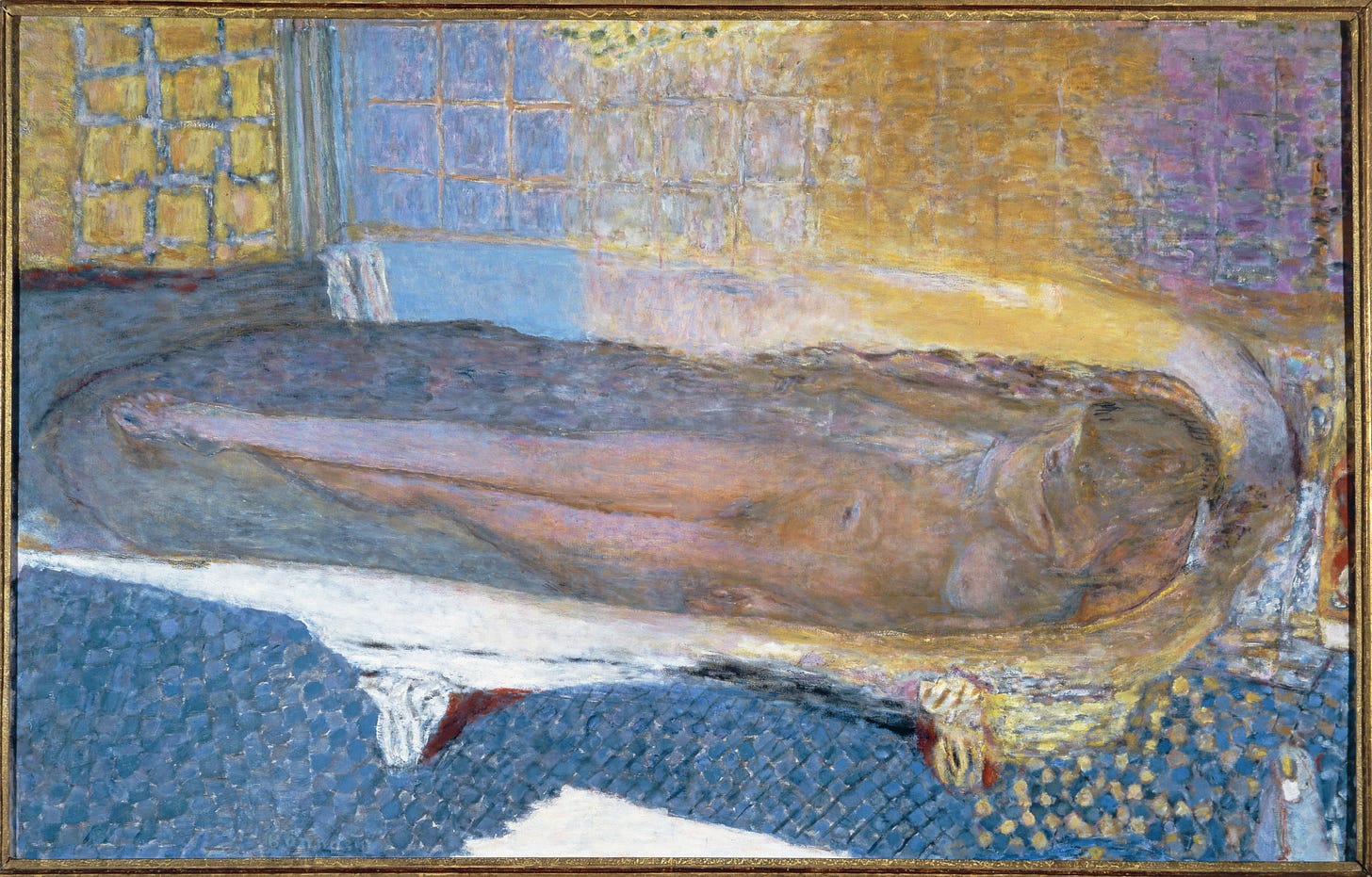

One of the galleries of “Bonnard’s Worlds” focuses unabashedly on Marthe bathing. With Nude in the Bath (1936), Bonnard composes Marthe stretched entirely submerged in water.

The tenderly rendered Nude in Bathtub (1941–46) was the last of Bonnard’s paintings of Marthe soaking in the bath. Alive when he began the painting in 1941, Marthe died the next year, and Bonnard completed the work from memory four years later. Given the complications of their half-century-long relationship, and the central role Marthe played in his artistic vision, it is no surprise that, as the catalogue notes, “her death left him forlorn” and he “grieved for her intensely.”

In addition to paintings, Bonnard also worked in popular graphic arts, such as posters, journal covers, book illustrations, and murals. The exhibition shows two examples: For poet Paul Verlaine’s collection Parallèlement (1900), Bonnard offered 109 lithographs and 9 woodcuts, mostly nudes of Marthe; and for an edition of the ancient Roman tale of Daphnis and Chloë (1902), he contributed 156 lithographs.

It was an inspired decision to organize the show by what mattered most to the artist, rather than by a strict chronology of his career. The design of the exhibition, bolstered by wall colors that enhance the art, immerse viewers in Bonnard’s life. We sit at his table, wander through his gardens, and feel the sunshine radiating from his works. As much as “Bonnard’s Worlds” is a thoughtful exhibition, it is also joyful theater.