Why Has America Forsaken Europe?

As the continent is riven by crises, the United States doesn’t seem to have a strategy, a policy, or even a goal for their relations.

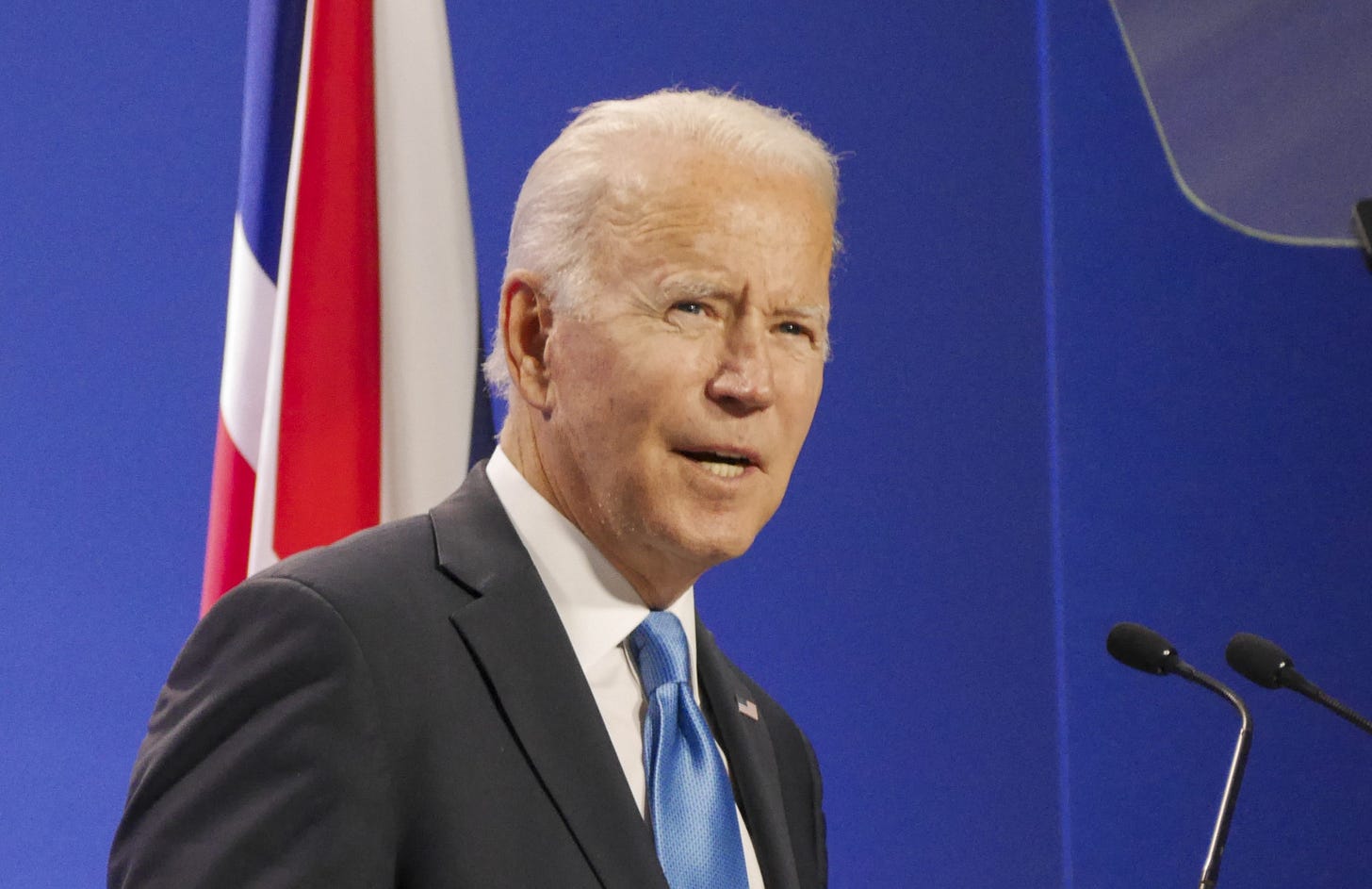

President Joe Biden inherited from the Trump administration the emerging bipartisan consensus that China is the one all-consuming, enduring challenge to America’s role in the world. Perhaps. Yet the problem with focusing so singularly on one country or region is that the others don’t go away. Europe is facing simultaneous crises more significant than anything seen since the fall of the Soviet Union, and the United States, under four consecutive administrations, doesn’t seem to know what to do, how to help, or even what it wants.

For years, Europeans have heard repeated American promises to focus more on Asia. The Obama administration, amid already tense trans-Atlantic relations, announced a “rebalance to Asia,” later characterized as a “pivot.” The inference in Europe was clear: More attention to Asia meant less attention to Europe. Trump declared NATO obsolete, repeated Obama’s insult that America’s European allies are “free riders,” encouraged Brexit, and tried to withdraw all American forces from Germany. Biden’s singular focus on China to the exclusion of other issues is only reinforcing the idea that American indifference to Europe transcends leaders and parties. America’s allies inferred that the guarantor of peace and stability since World War II might not be trustworthy. Those seeking to upend, curtail, or challenge that peace and stability sensed opportunity. Out of insecurity, some European governments have responded by rearming, and others by adopting a more conciliatory posture toward Russia.

Across the continent, decisions are being made accordingly. From the Baltic to the Adriatic, peace, stability, and democracy in Europe are starting to crumble. With Russian protection, and possibly direction, Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko is weaponizing migrants, jetting desperate souls from war-torn regions in the Middle East and South Asia and pushing them across the borders of Poland and Lithuania. Lukashenko is also threatening to cut off Europe’s energy supply. Simultaneously, Putin is mobilizing Russia’s armed forces on the Ukrainian border, perhaps preparing for an invasion. In the Balkans, incendiary rhetoric and threats by Milorad Dodic, leader of the Serbian autonomous region within Bosnia and Herzegovina, have brought war closer than at any point since the 1990s. Only the interposition of a NATO force ended violence between Serbia and Kosovo earlier this fall. On the opposite end of the continent, an attack on a bus in Northern Ireland has recreated images of other past conflicts once thought resolved.

These crises come at a moment of instability in Europe. Traditional positions of leadership are in flux: Within the last 12 months, a new administration has taken over in Washington, D.C., and Germany held elections to replace Chancellor Angela Merkel after 16 years of continuous leadership—elections which have yet to produce a successor. Despite heartening results from recent Central European elections, democratic backsliding remains a concern in Hungary and Poland. The war in Donbas is approaching its eighth year, as Russia still occupies Crimea, a piece of eastern Ukraine, and a fifth of the territory of Georgia.

But the Biden administration has been mostly absent amid Europe’s troubles. The president’s summit with Putin made a point of “strategic stability,” the implication being “we don’t want any distractions as we need to focus on China,” never mind Putin’s habit of promoting chaos and instability abroad. The failure to coordinate a response to Belarus’s act of piracy against a Ryanair flight likely emboldened both Lukashenko and Putin. Earlier this year, the administration delayed a package of military aid to Ukraine just as Russian forces were massing at the border. The decision not to invite Hungary to the Summit for Democracies is a meaningful gesture, but an especially weak one given the authoritarian governments invited. In response to Lukashenko’s flagrantly destabilizing migrant warfare, with its associated human rights abuses, the administration has so far offered only verbal condemnation.

Not surprisingly, trans-Atlantic relations are in disarray. Just over the past year, the United States and its European allies have found themselves at odds over a range of issues. The United States reacted with dissatisfaction to the trade agreement between the European Union and China, which Angela Merkel forced through in the waning days of her EU presidency. The Afghanistan blunder caught many in European capitals by surprise and forced them to scramble to evacuate their citizens. The rollout of the AUKUS agreement led to a diplomatic row with France, but it reflected what many see as the United States’s view of Europe: We will do what we need to regarding China, never mind the effects on our long-standing European allies. The Biden administration’s green light to Germany to complete the Nord Stream 2 project, led by a former Stasi agent and a friend of Putin, has angered many European countries, as well as some in the German opposition. The new administration waited until this month to rescind any of the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration against European goods, and even then left most of them in place.

If there’s any defense to be made of the administration’s confusion and listlessness in Europe, it’s that they’re merely continuing a pre-existing policy of inattentiveness to Europe.

But Biden had an opportunity to forge a new European policy. He spoke often about a foreign policy focused on human rights during his campaign—exactly the kind of policy that could invigorate NATO, which considers itself an “alliance of values,” and the EU, which is struggling to manage rising authoritarianism among its members. In his first months in office, Biden correctly and publicly called Putin “a killer.” He pledged repeatedly to repair American alliances, and he seemed to be signaling that he knew how to do it—by recommitting to the core values we share with our allies and speaking frankly about our adversaries. With three years left in his term, it’s not too late to bring the actions of the administration in line with the rhetoric of the president.

The United States needs Europe to be peaceful because it needs NATO and the EU to be productive. The size of Europe’s economy makes it an important counterbalance to China’s growth. British, French, and Spanish ties with Africa are important in pushing back against China’s growing influence in the continent. European universities still produce stellar research which is crucial in the technological competition with China.

Each of Europe’s strengths in a competition with China also makes it an important region in its own right. With three-quarters of a billion people, it is an important trade partner and plays a key role in the American economy. It is home to many U.S. military bases used for important missions, most recently during the evacuation from Afghanistan. Its scientific and technological achievements contribute to American prosperity—the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine that the president of the United States and millions of others recieved would not have been made without German partnership.

America can’t afford to take Europe for granted anymore. They need us and we need them. The hard part of alliance management is supposed to be responding to the needs, wants, and objectives, and insecurities of the other side. But lately, the United States has had more trouble figuring out what its own needs, wants, and objectives in Europe are—or if it has any at all.