Why I Don't "Believe" in "Science"

Science isn't about "belief." It's about facts, evidence, theories, experiments.

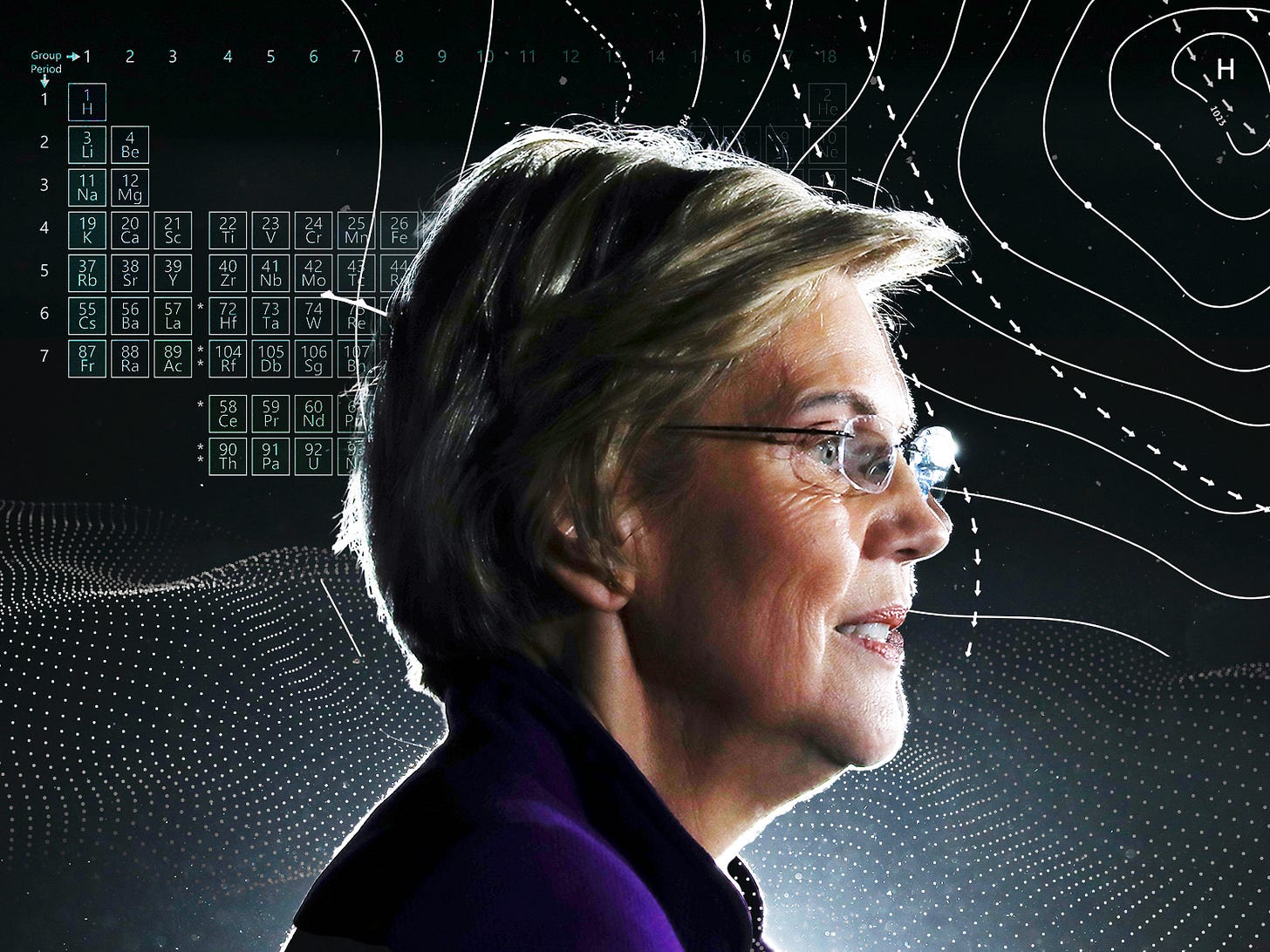

For some years now, one of the left's favorite tropes has been the phrase "I believe in science." Elizabeth Warren stated it recently in a pretty typical form: "I believe in science. And anyone who doesn’t has no business making decisions about our environment." This was in response to news that scientists who are skeptical of global warming might be allowed to have a voice in shaping public policy.

So what Warren really means by saying “I believe in science” is “I believe in global warming.”

But we owe it to Andrew Yang—a Democratic presidential candidate who just managed to qualify for the televised primary debates by getting more than 65,000 individual campaign contributions—for stating this trope in such a comical form that it gives the game away:

"My father has a Ph.D. in physics,” he said. “I believe in science."

This prompted some well-deserved mockery along the lines of, "My father was a cartoonist. I believe in Daffy Duck." More important, it captures a lot of what annoys the rest of us about the "I believe in science" crowd. It reduces a serious intellectual issue—a whole worldview and method of thought—to a signifier of social group identity.

Some people may use "I believe in science" as vague shorthand for confidence in the ability of the scientific method to achieve valid results, or maybe for the view that the universe is governed by natural laws which are discoverable through observation and reasoning.

But the way most people use it today—especially in a political context—is pretty much the opposite. They use it as a way of declaring belief in a proposition which is outside their knowledge and which they do not understand.

There are a lot of people these days who like things that sound science-y, but have little patience for actual science. These are the kind of people who gush when Elon Musk tells them he's going to put a million people on Mars but seem less excited about discussions of cosmic-ray shielding, or solar wind, or hydrogen escape, or all the reasons why Mars is a dead planet.

They prefer the imagery of “science” to the more prosaic reality. In my experience, "I believe in science" is just a shorthand way of admitting, "I have a degree in the humanities."

The problem is the word "belief." Science isn't about "belief." It's about facts, evidence, theories, experiments. You don't say, "I believe in thermodynamics." You understand its laws and the evidence for them, or you don't. “Belief” doesn't really enter into it.

So as a proper formulation, saying "I understand science" would be a start. "I understand the science on this issue" would be better. That implies that you have engaged in a first-hand study of the specific scientific questions involved in, say, global warming, which would give you the basis to support a conclusion. If you don't understand the basis for your conclusion and instead have to accept it as a "belief," then you don't really know it, and you certainly are in no position to lecture others about how they must believe it, too.

Because science is about evidence, this also means that it carries no "authority." The motto of the Royal Society is nullius in verba—"on no one's word"—which is intended to capture the "determination of Fellows to withstand the domination of authority and to verify all statements by an appeal to facts determined by experiment."

That's the opposite of what "I believe in science" is intended to convey. "I believe in science" is meant to use the reputation of "science" in general to give authority to one specific scientific claim in particular, shielding it from questioning or skepticism.

"I believe in science" is almost always invoked these days in support of one particular scientific claim: catastrophic anthropogenic global warming. And in support of one particular political solution: massive government regulations to limit or ban fossil fuels.

But these two positions involve a complex series of separate scientific claims—that global temperatures are rising, that humans are primarily responsible, that the results are going to be catastrophic for human life, that rising temperatures can be halted—combined with a series of economic and political propositions. For example: that action to ban fossil fuels would be more efficacious than using the wealth made possibly by fossil fuels to help humans adapt to future climatic changes.

The purpose of the trope is to bypass any meaningful discussion of these separate questions, rolling them all into one package deal--and one political party ticket.

The trick is to make it look as though disagreement on any of these specific questions is equivalent to a rejection of the scientific method and the scientific worldview itself.

Historically, this makes no sense. There are many theories, even in the relatively recent past, that were widely accepted as the scientific “consensus” and later debunked, and there have been many theories initially dismissed by the mainstream as crackpot notions that were later confirmed. Look at the history of plate tectonics, or the solar wind, which both took decades to win acceptance by the mainstream of their fields. Or consider the recent conclusion that research on Alzheimer's may have been misdirected for decades based on premature adoption of an incorrect theory.

The point isn't just that scientists can get things wrong. The point is that science is hard.

The scientific method is very powerful, but the questions it is attempting to understand are often extremely complex and intractable. And scientists themselves are human—prone to biases, blind spots, and groupthink. (A geologist recalls, "I had been told as an undergraduate at MIT that good scientists did not work on foolish ideas like continental drift.")

But when people in politics proclaim "I believe in science" what they’re doing is proclaiming a belief in the current consensus. Do you think Elizabeth Warren and Andrew Yang have given serious study to climate science? No, they believe in global warming and its preferred political solutions because they have been told that a consensus of scientists believes it (and because this belief confirms their own political biases). Notice that Warren's statement was about a panel of scientists who are skeptical of global warming, led by a distinguished physicist, William Happer. When does a scientist count as someone who "doesn't believe in science"? When he departs from the "consensus."

The people who say this sort of thing probably don't know it, but they are parroting the legacy of 20th-Century philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, who is responsible for elevating consensus over evidence. He argued that evidence and experiments could not distinguish between true and false theories because scientists would always spin and rationalize the results away, making ad hoc adjustments to their theories to support their predetermined scientific loyalties. As an analysis of consensus gone wrong, this was pretty much correct. But Kuhn argued that this was the only way science could work, that there was no objective means of solving disagreements, that the change from an old theory to a new one cannot be "forced by logic and neutral experience." So a scientific revolution or "paradigm shift"—he coined the term—was always at root a matter of changing social consensus.

Like I said, this is an excellent description of a scientific consensus gone wrong. And that's what leads us back to the real meaning of "I believe in science." It is a way of declaring one's loyalty to a social consensus. In Andrew Yang's case, it's a way of telling his audience that he was literally born and bred in the right social group, the one that preens itself on a very self-conscious image of being "pro-science" and uses this to differentiate itself from it political rivals, whom it casts as obscurantist religious fanatics who are "anti-science."

That's what I mean when I say that this is an homage given to science by people who generally don't understand much about it. Science is used here not to describe specific methods or theories, but to provide a badge of tribal identity.

Which serves, ironically, to demonstrate a lack of interest in the guiding principles of actual science.