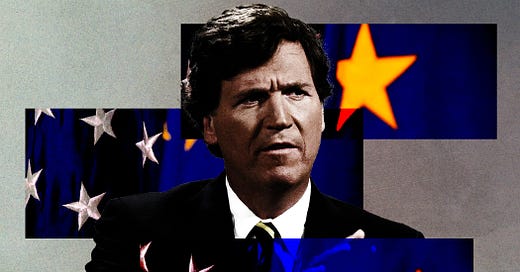

Why the EU Could Sanction Tucker Carlson

He won’t be banned from Europe, but Europe might be better off if he were.

THE IDEA THAT THE EUROPEAN UNION may consider sanctioning Tucker Carlson for his interview with Vladimir Putin—first floated by Guy Verhofstadt, a liberal member of European Parliament and former prime minister of Belgium—seems dead in the water. But that has done little to attenuate outrage and wild speculation, particularly on the Putin-curious right.

Elon Musk called the suggestion that Carlson might be denied entry into Europe “disturbing.” True to his reputation, Vivek Ramaswamy immediately invented a conspiracy theory: The EU could never take such a move (which, to be clear, it hasn’t taken) “without implicit blessing from their counterparts in the U.S. government.” Viktor Orbán’s political director, meanwhile, promised that the Hungarian government “won’t let it happen.”

Of course, there are currently “no discussions in the relevant EU bodies” about sanctioning Carlson, according to the European Commission’s spokesperson. Even if there were, any measures targeting him would face legal obstacles and political battles (not least because allies generally sanction each other’s nationals only in extreme circumstances)—and besides, the EU can’t do anything that quickly.

That said, the EU and/or its member states would be fully within their rights to sanction Carlson—if they perceive him as engaged in activities that harm their collective interest. The Commission’s spokesperson added that the EU could, theoretically, sanction “propagandists” who have a “track record” of working to “undermine the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine and to promote the illegal and brutal aggression by Putin.”

Sovereign states—or, in the case of the EU, supranational organizations—have almost by definition the plenary power to vet who gets into their country—a power Carlson and his supporters would no doubt defend, and indeed have defended.

Given the importance of Ukraine to Europe’s security, it would be reasonable for the EU to refuse entry to those who support Russia’s effort to wipe Ukraine off the map. In fact, since the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it has become much harder for Russians to obtain visas to the EU. Opinions will differ on whether closing the border to Russians (or to Carlson) is wise, but it is hardly illegitimate.

Denying entry to a foreigner is not a free-speech issue. Carlson is free to write and broadcast, and Europeans are as free as Americans to watch his two-hour interview with the Russian dictator for themselves and think for themselves, just as Carlson encouraged them to.

It seems unlikely that many Americans or Europeans were convinced by Putin’s rambling exposé of the supposed historic unity of Russians and Ukrainians going all the back to the ninth century. The audience was really a domestic one. As Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Putin’s exiled opponent, notes in the Telegraph, Russians “have largely Western tastes, behavior and consumption patterns”—in short, they see the West both as a “bully and a role model.” Carlson, depicted in Russian propaganda as a titan of America’s media market, provided validation for Putin’s lunatic views.

Carlson is a familiar figure in Russia. He has been frequently clipped and quoted on Russian TV—at the orders, apparently, of the government itself. He has consistently echoed Putin’s talking points justifying the war against Ukraine, lambasting U.S. support for Ukraine, and accusing NATO and the West of provoking violence there. He has also parroted Russian propaganda about U.S. biolabs in Ukraine, and about Russia being a deeply Christian country defending traditional values again the onslaught of wokism.

Putin made it clear before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine that his goal wasn’t just to gobble up his neighbor, but to assert a Russian sphere of influence over much of Europe, including several current EU members. Given the threat that Putin and his regime pose to European security, it would be reasonable for European leaders to conclude that Carlson’s work, bolstering Putin’s image ahead of a presidential election, makes him an undesirable visitor to the continent.

Would it be a wise, prudent move to ban him from Europe? Probably not—which is why it’s unlikely to happen. Especially for those EU member states that most strongly support Ukraine, sanctioning Carlson could backfire, making it even less likely that Republicans in Congress will approve the aid package for Ukraine currently under consideration.

If, however, that package fails, and Europeans conclude that the United States has abandoned Ukraine and, by extension, all of Europe, there may be more reason to deal more harshly with Putin’s useful idiots and fellow travelers in the West, including in the United States. It’s not about shutting Carlson up—it’s just about keeping him out.