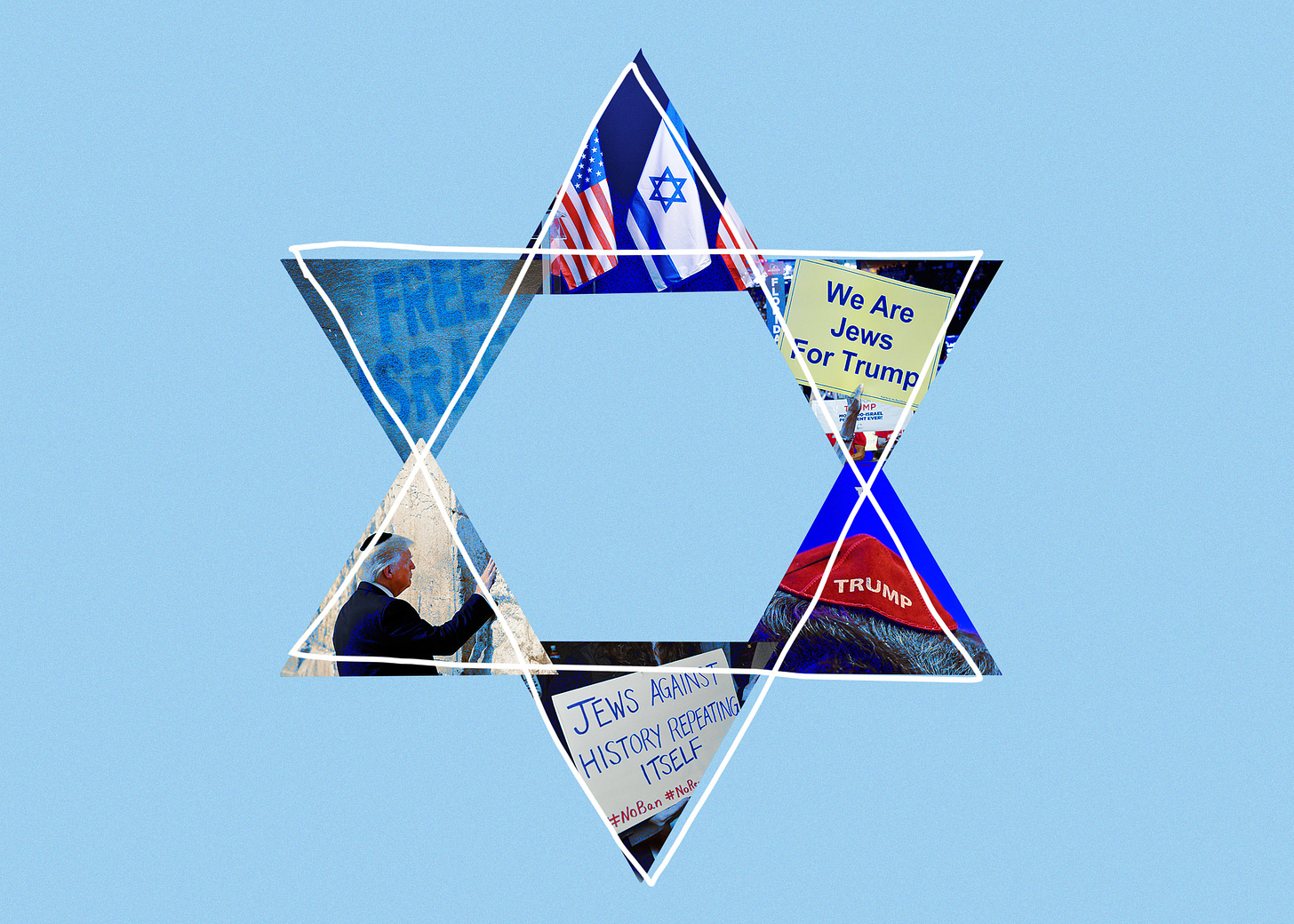

Would Trump Be Better for Israel and the Jews?

Many American Jews are irrationally forgiving of the former president and unnecessarily wary of Kamala Harris.

WITH LESS THAN TWO WEEKS LEFT to go, the presidential race is hanging by a thread. The outcome may hinge in part on Jewish voters in the seven swing states. A recent poll of American Jewry commissioned by the Manhattan Institute found Kamala Harris garnering approximately two thirds of Jewish voters—a low fraction for a Democrat, and indeed a number that puts her, according to the Manhattan Institute’s pollsters, “on track to perform worse in this year’s election than any Democratic presidential candidate since the Reagan era.”

Unsurprisingly, issues of Israel, security, and antisemitism loomed large for survey respondents, who rated only abortion, the economy, and democracy as more important issues. To anyone worried about a possible second Trump presidency emerging out of an extraordinarily close race, this shift in Trump’s direction among Jewish voters should be extremely concerning. Now that a trio of former Trump advisers and appointees—all former military officers—have come forward to warn that Trump is a fascist or has fascist proclivities, the Jewish shift toward Trump has assumed a new salience. It appears to reflect a series of judgments that require urgent and candid analysis. Looking back, over the past eight years, was Trump or Biden a better friend to Israel? Looking ahead, would Trump or Harris be a more reliable supporter of the Jewish state? What would be the impact of Trump or Harris on U.S. foreign policy more generally and on America’s role in the world? Foreign policy aside, which candidate would be better at defending democratic institutions and upholding the rule of law on which the freedom and security of all Americans, not least American Jews, ultimately depend?

SINCE OCTOBER 7th, American support has been essential to Israel’s ability to wage a multi-front war against Hamas, Hezbollah, the Houthis, and Iran. The Biden administration has provided the IDF with a steady flow of weapons ranging from dumb bombs to, most recently, the highly advanced THAAD anti-ballistic missile system (to be operated by American soldiers). It has engaged in extensive intelligence sharing with Israel, including in the search both for hostages and high-value Hamas targets. Biden has deployed a naval armada in the eastern Mediterranean to deter and to defend against Iranian attacks on Israel. As it did in the first Gulf War, the United States has employed its forces to defend Israel, helping to shoot down fusillades of Iranian cruise and ballistic missiles on both April 13 and on October 1. President Biden, who has declared himself a Zionist, is the first American president to visit Israel during wartime—his eleventh visit to the Jewish state.

Yet Biden’s support has not been unequivocal. In May, he leaned heavily on Israel not to enter the southern Gaza city of Rafah, and he even placed a temporary embargo on the shipment of 2,000-lb. bombs to Israel. The administration has publicly intimated that Israel has been reckless in its treatment of Palestinian civilians, both in the way it has been waging war and in failing to provide humanitarian aid to the inhabitants of the Gaza strip, going so far as to threaten an arms embargo if Israel did not step up humanitarian assistance. And the administration has reportedly pressed Israel to show restraint in responding to Iran’s attacks and support for Islamist extremists. Whatever the wisdom of these positions, Biden has fended off pressure from some in his own party to curtail support for Israel. Despite points of disagreement and friction, his administration’s record of backing Israel has gone far beyond that of any previous American president in wartime.

Donald Trump’s insistent claim that, had he been president, Hamas would never have attacked Israel is his usual empty bluster. Still, Trump can boast a strong record of support for the Jewish state. As president, he fulfilled the longstanding promise of successive Democratic and Republican presidential candidates to move the American embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. He recognized Israel’s 1981 annexation of the Golan Heights, captured from Syria in the 1967 Six Day War. He launched a strike killing the Iranian Quds Force terrorist commander Qassem Soleimani. He pulled out of the flawed Obama-administration nuclear deal with Iran and re-imposed strict economic sanctions. His administration helped to negotiate the Abraham Accords, bringing peace between Israel and some of its Arab neighbors: Bahrain, the UAE, Morocco, and Sudan.

As a presidential candidate, Trump has cast himself as Israel’s defender and claimed that the Jewish state will soon cease to exist unless he’s elected. “It’s total annihilation—that’s what you’re talking about,” Trump said, addressing the Israeli-American Council summit in Washington, D.C, at a gathering commemorating October 7th. “You have a big protector in me. You don’t have a protector on the other side.”

Unfortunately, past is not always prologue. America’s longstanding support for Israel has always been based upon Israel’s unique status as a flourishing democracy in the Middle East. But Trump has never expressed anything but disdain for the idea of supporting fellow democracies, be they in the Middle East, Europe, or anywhere else. As with all other aspects of his foreign policy, including his affinity for Vladimir Putin and his hostility to America’s traditional democratic allies, Trump’s support for Israel is rooted not in principle but in narrow, personal considerations. The positions he took during his first term may have reflected in part the influence of Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner, his Jewish daughter and son-in-law, as well as his own pursuit of electoral advantage. But Ivanka and Jared have withdrawn from political life to pursue dubious business deals, including with Saudi Arabia. And Trump, if re-elected, will be a lame duck president from the outset, with no need to concern himself with cultivating Jewish voters.

Aside from Trump’s substantial business dealings with Arab autocrats, what will remain in a second Trump term is his affinity for and personal relationship with Benjamin Netanyahu, who over the past eight years has assiduously and skillfully flattered the flattery-prone former president. Their relationship frayed considerably in December 2020, when Netanyahu had the temerity to congratulate Biden on his electoral victory, enraging Trump as he tried to cling to office. Whatever their relationship going forward, there is no guarantee that Netanyahu will remain on the political stage for long. Trump’s relationship with a successor Israeli prime minister, especially following his close association with one who is deeply unpopular with many Israelis, is an entirely open question.

With the election contest underway here at home, Trump—directly countering the Biden administration—has been calling for Israel to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities. But talk is cheap. Trump has said nothing to suggest that he would favor U.S. participation in such an attack. Nor is there anything in his record to indicate that he would be willing to throw the dice and bring the United States into a major war that would almost certainly entail American casualties, as well as disrupting energy markets and potentially destabilizing the global economy. It is telling that as president, he once canceled a small-scale reprisal strike against Iran at the last minute because he feared it would have caused Iranian casualties; no Americans were in harm’s way.

If Trump’s foreign policy worldview has one consistent feature, it is a deep skepticism about the value of allies, whom he cynically sees not as fellow democracies, but as freeloaders prone to drawing America into wars in which we have no interests of our own. Throughout Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, Trump has steadfastly taken Russia’s side, even suggesting that Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelensky is responsible for the conflict. He has repeatedly admonished South Korea for not paying the United States for its defense, treating the alliance (like NATO) as a kind of protection racket. And he has voiced doubts about the value of defending Taiwan and accused it of stealing America’s semiconductor industry in comments that could tempt Chinese aggression and pave the way for American abandonment of the island nation. Why should Israel expect better treatment in the event of a major conflict?

ONE OF THE MAIN REASONS why some Jewish voters are skeptical of Harris is the fear that she might be more prone than Biden to give in to pressure from the left wing of her party, perhaps drastically curtailing support for Israel. Yet there is very little evidence to support such fears.

Despite being in the delicate position of attempting to court Arab-American voters in Michigan, Harris has repeatedly stated not only that Israel has a right to defend itself but also, more importantly, that “I will always ensure Israel has the ability to defend itself.” In contrast to Trump, whose personalization of the relationship and close association of U.S. national interests with those of Benjamin Netanyahu may have undermined support for Israel by a significant segment of the American public, Harris has been unequivocal in stating that her commitment is to the people of Israel rather than to any particular government. This is entirely appropriate and consistent with America’s long-term interests in the Middle East, as are her expressions of sympathy for the suffering of innocent Palestinians caught up in the fighting in Gaza.

Even if Harris wanted to somehow overhaul a decades-old policy of unstinting U.S. support for Israel, she would face overwhelming opposition from both Democratic and Republican members of Congress, as well as from large majorities of the American public. There is more reason to believe that Harris would be a reliable supporter of Israel than to imagine that Trump’s backing would be rooted in anything sturdier than fickle whims and infinitely flexible calculations of narrow self-interest.

On broader questions of U.S. foreign policy, Harris is clearly well within the American mainstream, supporting a forward-leaning position in the world. Trump stands outside of the mainstream. Indeed, a second Trump presidency is likely to usher in an era of unparalleled global chaos. The dissolution of NATO that Trump has repeatedly threatened, the Russian victory that is likely to follow his abandonment of Ukraine, and the trade wars that he is promising to unleash via unprecedented tariffs on friend and foe alike will be the final nails in the coffin of the global order that has prevailed since World War II. Far from thriving, the prosperity and security of America’s allies everywhere—very much including Israel—will be in jeopardy in such a dangerous and unpredictable environment.

AS IMPORTANT AS SUCH ISSUES ARE to American Jews, this is not solely or even primarily an election about Israel or even about foreign policy more broadly defined. At stake are the stability of our society, the resilience of our political and legal institutions, and even the durability of our democracy. Trump is clearly a threat to all three.

A country in which the government is engaged in constructing detention camps, forcibly separating families and expelling millions of undocumented immigrants, in which police feel emboldened to use deadly force without fear of legal consequences, and religious nationalists feel empowered to try to impose their views on others is not one in which any minority, least of all Jews, could feel safe.

For the last few years, and particularly since October 7th, there has been an explosion of antisemitism in the United States, particularly on college campuses. Harris and mainstream Democrats have rightly denounced the pro-Hamas demonstrators. But Trump has long flirted with right-wing antisemites and conspiracy theorists and gratefully welcomed their support. When marchers chanted “Jews will not replace us” in Charlottesville, Trump spoke of “good people on both sides.” Since leaving office, he has dined with openly antisemitic celebrities and neo-Nazi internet trolls. Trump, along with his running mate JD Vance, has maintained close ties with Tucker Carlson even after Carlson hosted a Holocaust-denying “historian” on his show. He has stood by North Carolina gubernatorial candidate Mark Robinson notwithstanding his status as an open antisemite, Holocaust denier, and self-described “black NAZI.” Thanks in large measure to Trump’s degradation of public discourse, what was unthinkable a decade ago has now been completely normalized.

Most recently Trump has indulged in some menacing rhetoric of his own, using language that is frankly Hitlerian, calling his political opponents “vermin” and “the enemy within” and accusing migrants of “poisoning the blood” of our country. According to General John Kelly, his former chief of staff, Trump repeatedly avowed that “Hitler did some good things.” In September, he warned, “If I don’t win this election, the Jewish people would have a lot to do with a loss.” If he does in fact lose, some of Trump’s supporters, among others, will no doubt blame the Jews. And if he wins, but with two-thirds of America’s Jews voting against him, what then? For a man invested with enormous powers, and as someone who has often stereotyped Jews in dubious ways—as greedy and disloyal to the United States—the scapegoating in advance points to an obvious danger lurking. If the history of the last century teaches us anything, it is that hateful words and ideas have consequences. Anyone who doubts this should consider the tragic events at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue, where in 2018 an armed fanatic, inflamed by the atmosphere of anti-immigrant hysteria Trump has done so much to create, brutally murdered eleven congregants.

In the end, the choice between Trump and Harris comes down to how voters weigh the relative risks of the two. One is a dangerous, increasingly uninhibited, and openly authoritarian demagogue obsessed with the prospect of deporting immigrants, imposing tariffs, pulling back from global commitments, and wreaking vengeance on his domestic opponents. The other, despite Republican efforts to paint her as an extremist, is an unexceptional, middle-of-the road Democrat, wholly in the American mainstream. A dispassionate appraisal suggests that there is a greater risk that Trump will do irreparable damage to our institutions and to the global order—injuring American Jews and Israel along the way—than that Harris, whatever her shortcomings, will do grievous harm to this country or to Israel. For Jews, this election should not pose a tough choice.

Aaron Friedberg is a professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton University. Gabriel Schoenfeld was a senior adviser to Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign.