You Need More Puccini in Your Life. Here’s Why.

Exactly 100 years after his death, the giant of Italian opera still thrills and chills.

AMONG PEOPLE WHO KNOW ME, I am famous—or maybe notorious would be a better word—for circulating links to music. I’m constantly firing out messages to friends, colleagues, WhatsApp groups, Instagram DMs, saying “Stop whatever you’re doing! You have to listen to this.” Any sort of music makes the cut, so long as it’s good; recent selections have included Oscar Peterson’s version of “Witchcraft” (the most stylish thing I’ve heard in a long time), Chet Baker’s “My Funny Valentine,” “Somewhere” from West Side Story, and of course, a healthy dose of classical music, like ten of the most moving seconds Mozart ever penned (to be found, somewhat unexpectedly, in his Concerto for Flute and Harp).

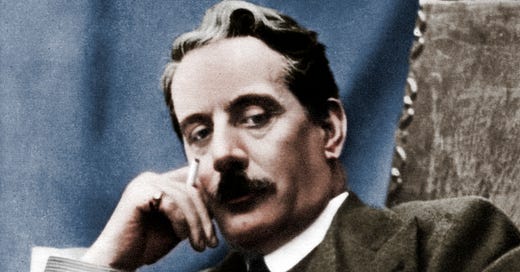

Naturally, now and then I send around excerpts by Giacomo Puccini. I am one of those millions around the world for whom the great Italian opera composer—who died one hundred years ago today, on November 29, 1924, at the age of 65—has always occupied a special place. Puccini was a true life-lover and bon vivant: He drank, he smoked, he loved fast cars and fast boats, he was a hunter, a fisherman, he wrote recipes, he drank espresso and chain-smoked till all hours of the while night composing, he cooked for friends, he had an avid lovelife. He seems, in short, to have been an utter joy to be around (except at times for the wife who put up with his womanizing).

There are many reasons for Puccini’s enduring critical success and the massive popularity, even dominance, of his operas still to this day. For one, anyone can appreciate the approachability of his characters and the simplicity of the stories of his operas. Whether it’s four struggling artist roommates and their love lives (La Bohème), a rage of deep romantic jealousy turned violent (Il Tabarro), or a hilarious, romping comedic telling of missed opportunities at a wealthy family members inheritance (Gianni Schicchi), the stories of most Puccini operas are immediately relatable.

But deeper than the stories, there is the music: colorful, lush, grand and intimate, vast and deeply personal all at the same time. Puccini creates the most incredible musical waves that sweep and swoosh over you. In the space of seconds his music can reduce you to tears, an emotional assault of the most delicious and cathartic sort.

Here’s my theory about why his music remains so irresistible: Puccini can create frisson—a sudden physical thrill, like a chill or shiver or tingle of excitement—more easily than any other composer.

I am not a scientist and I wouldn’t attempt to explain how or why this happens (although if you want to check out Wikipedia to read about the physiology of “transient paresthesia,” “piloerection,” “mydriasis,” and more, be my guest). I just know that Puccini’s music does quite often provoke a frisson—I have experienced it myself powerfully and repeatedly in the same exact passage of music, I have witnessed it with others, and have seen tough anti-Romantic skeptics emotionally destroyed by one phrase of Puccini’s music.

And you know what? We should lean into that. In a time of algorithms and inauthenticity, we need more raw emotion. We need to share more musical moments alone or with loved ones. We need more frisson.

We need more Puccini.

Here are five of my favorite Puccini moments. They’re all brief but powerful, and they all go straight to the heart with Puccini’s trademark sweep, the blending of the intimate and the grand. Have a listen and share these with your own friends. This music may not fix the world, but it might just temporarily fix your world.

Butterfly’s Entrance from Madama Butterfly

This three-minute clip epitomizes Puccini. Set in Nagasaki, Japan in 1904, the opera tells the story of the American Naval officer Pinkerton, his marriage to the beautiful young Japanese girl Cio-Cio San (Madama Butterfly), and the tragic ending that ensues. In this scene, from Act I of the opera, Pinkerton witnesses with adoration both the incredible traditional grand Japanese entrance of Butterfly and the physical beauty of Butterfly herself (here sung by Mirella Freni). Listen to how the solo violin mirrors and enhances the voice. Listen to how every chord change is more heart-wrenching than the one before. Listen to the way Butterfly’s voice seems to float to heaven itself. Listen to the prominence of the harp weaving the most magical lines around the main voices. Just listen. It’s exquisite.

Act I Love Duet from La Fanciulla del West

Puccini’s sprawling so-called “American opera” La Fanciulla del West premiered in 1910. Based on The Girl of the Golden West, a play by David Belasco,1 La Fanciulla is set during the gold rush of the 1850s in a California mining town in the Sierra Mountains. It has some of the richest, most powerful music ever to make it to the operatic stage. This selection, a full fifteen minutes, is the expansive love duet at the end of Act I between Dick Johnson, a disguised bandit, and Minnie, the tough saloonkeeper who presides over the miners—part mom, part teacher, part cheerleader. In this duet, which takes place in Minnie’s cabin, she lets down her guard to Johnson and reveals her deep doubts about her physical appearance, education, and self-worth. In music there’s an expression called “long line”—the idea, or really ideal, that a phrase can go on, seemingly endlessly, and transport us with the power of its musical connective tissue. This duet has numerous examples of the long line, as sung here by Gigliola Frazzoni and Franco Corelli. Be patient and listen to the whole fifteen minutes. Thank me afterwards.

Recondita armonia from Tosca

Set in Rome in 1800, Tosca has some of Puccini’s best-known music. In Act I, the painter Mario Cavaradossi arrives at Rome’s famous St. Andrea della Valle Church to continue working on his painting of Mary Magdalene. The church’s sacristan (a junior employee) observes that the face in the painting looks startlingly like that of a woman who has been visiting the church to pray recently, Floria Tosca. In “Recondita armonia,” our painter hero Cavaradossi sings about the “concealed harmony” between Floria Tosca and Mary Magdalene. This is the classic tenor aria and the legendary Luciano Pavarotti is the perfect vessel for this piece.

Senza mamma from Suor Angelica

Suor Angelica is one of the hour-long operas that make up Il Trittico, the great triptych of unrelated short operas that make up a spectacularly varied and colorful three hours of music. Here, the main character, Sister Angelica, has been sent to a convent as retribution by her aristocratic aunt after Angelica gave birth to an illegitimate son. Right before this aria, the aunt has informed Angelica of the death two years prior of this very child. Beyond heartbroken, she sings this most delicate and heart-wrenching of arias professing her love for the son she never had the chance to raise.

Donde lieta uscì from La Bohème

La Bohème is the quintessential Italian opera. It certainly has all the hallmarks, musically and dramatically, that make Puccini’s operas so beloved—which makes it difficult to settle on just one selection. But I want you to listen to the brief but powerful aria from our doomed heroine, Mimì. She is singing to her former lover, Rodolfo, asking that they part amicably, requesting the return of the few possessions she left at his apartment, and offering one for him to keep in remembrance of her. By this point, the audience has heard Mimì’s coughing fits; we know, she knows, and Rodolfo knows that she has tuberculosis and that it will be her demise. In this recording, the great Italian soprano Renata Tebaldi gives us a vulnerable, delicate, and steadfast Mimì.

Belasco also wrote the play that inspired Madama Butterfly.