Peace Prize Pettiness

Misplaced Ukrainian pique over the prize being shared with regime critics from Russia and Belarus.

Last week’s announcement of the new Nobel Peace Prize honoring human rights advocates from Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia set off an odd war of words that brought into focus a simmering cultural and philosophical conflict on the edges of the actual war in Ukraine. At issue: whether everyone and everything Russian should be tarred with collective guilt for the war unleashed by Vladimir Putin. This year, the Peace Prize was shared by three recipients: Belarusian human rights activist Ales Bialiatski, the venerable Russian human rights group Memorial, and the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties. As the Nobel Committee put it:

The Peace Prize laureates represent civil society in their home countries. They have for many years promoted the right to criticize power and protect the fundamental rights of citizens. They have made an outstanding effort to document war crimes, human right abuses and the abuse of power. Together they demonstrate the significance of civil society for peace and democracy.

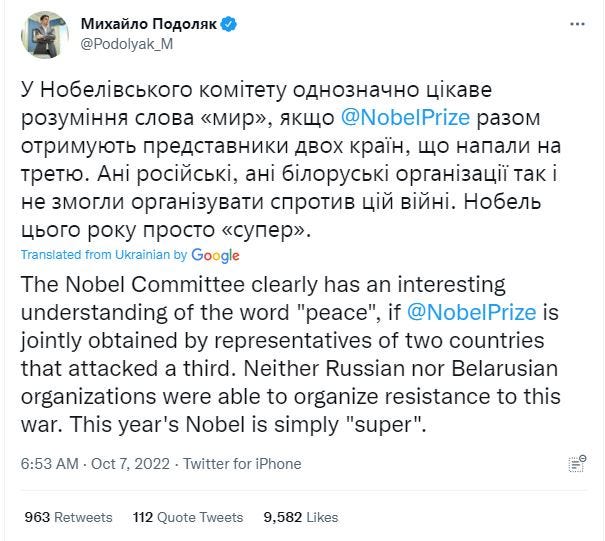

A number of Ukrainian voices reacted with criticism or even outrage—most notably Mykhailo Podolyak, a journalist and adviser to the office of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

But this is a peculiar complaint, considering neither Bialiatski nor Memorial are “representatives” of their respective countries in any official sense: if anything, quite the opposite. Bialiatski, the 60-year-old chairman of the “Viasna” (Spring) Human Rights Center, has been in prison since July 2021 awaiting trial on phony charges of tax evasion. Memorial, which was born in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s in the era of Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost as a group seeking to record, preserve, and publicize Stalin-era atrocities and post-Stalin Soviet repressions—and whose offshoot, the Memorial Human Rights Center, also focused on modern-day human rights abuses in Russia—was banned last December in the run-up to the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine. (Memorial was designated a “foreign agent” in 2016 and was eventually shut down for violations of the abstruse rules governing the work of organizations so branded.) Podolyak’s sentiment was echoed by many others—from the Kyiv Post, which backed his criticism on Twitter, to Berlin-based Ukrainian journalist Nikolai Klimeniouk:

This is the high art of the Nobel: to give the prize in such a way that the laureates are very worthy and yet the prize leaves a most unpleasant feeling. So—let’s stuff Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia into the same cookpot, if not in one way then in another? Why? To reward human rights activists from a democratic country together with ones from dictatorships—what sort of a signal does that send?

Some other Ukrainians activists , such as Ukrayinska Pravda editor-in-chief Sevgil Musayeva and lawyer and former parliament member Olena Sotnik, welcomed the award to Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties but also suggested, though in more measured tones than Podolyak, that the joint prize was inappropriate: “Without commenting on the merits of other human rights activists from hostile countries, it is morally wrong to put us on a par with them, separated by commas. Their countries are waging war against us!” Sotnik wrote on Facebook. Still others, not just Ukrainians but Estonian author Rein Raud, Kyrgyz journalist Bektur Iskender, and Russian émigré journalist Ostap Karmodi, focused their criticism on the Nobel Committee’s supposed placement of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia into one “basket” as three “fraternal peoples,” thus inadvertently reinforcing Putin’s colonialist idea. (These reactions were collected in an invaluable roundup by the dissident Russian website Grani.ru.) Even some who praised the award, such as Ukrainian journalist Irina Romaliyska, noted that the Belarus/Russia/Ukraine grouping shows that “the abstract West is still finding its way toward understanding Ukraine and the processes happening here.” Radio Free Europe journalist Elena Fanailova, whose initial reaction was to write on Facebook, “The fact that the Nobel Committee chose the ‘Slavic list’ indicates that Europe understands where the civil resistance front currently lies,” later apologized for using the term “the Slavic list” after blowback in the comments. The blowback is understandable amid the passions of war when new reports of the Russian army’s atrocities in formerly occupied Ukrainian territories are emerging every day—and when Putin’s military bombs cities and kills civilians on territories that Putin claimed as sacred Russian ground mere days ago. But the criticism is also profoundly misguided. For one thing, the claim that the joint prize to the “Slavic list” implies a lumping together of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia into a single “fraternal” basket—or even perhaps even into one big Greater Russia—reflects a basic ignorance about the way joint Nobel Peace prizes operate. In a number of cases, they have been given to individuals from different countries that have little in common when those individuals are in some sense working (not necessarily together) for the same cause.

One need look no further than last year, when the prize was shared by Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov (editor-in-chief of the dissident newspaper Novaya Gazeta, which has since battled the government’s attempts to shut it down) and Filipina journalist Maria Ressa; they were recognized “for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.” No one would interpret this as meaning that the Philippines are Russian territory. Three years earlier, in 2018, the co-recipients were Congolese doctor Denis Mukwege and Iraqi Yazidi activist Nadia Murad Basee Taha, “for their efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict.” “How about India and Pakistan?” Belarusian-born journalist Pasha Lesiants wrote sarcastically in a Facebook comment. But in fact, the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize did go jointly to “India and Pakistan”—or rather, to Indian children’s right activist Kailash Satyarthi and Pakistani schoolgirl and activist Malala Yousafzai, “for their struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education.” The Nobel Peace Prize is not given to countries, only to individuals or organizations. Claims that the Nobel Committee’s language in announcing the award somehow channels Kremlin rhetoric about “fraternal peoples” and Slavic unity are equally off base. The prize announcement says nothing of the sort. The longer press release does refer to the laureates as “outstanding champions of human rights, democracy and peaceful co-existence in the neighbor countries Belarus, Russia and Ukraine” and praises them for honoring “Alfred Nobel’s vision of peace and fraternity between nations.” But, well, it is called the Nobel Peace Prize; it’s a geographical fact that Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine are neighbor countries, which is hardly the same as the claim that Belarus and Ukraine should be reintegrated into the Russian empire; and the concept of “fraternity between nations” should still be allowed to exist even if, historically, it has been egregiously misused by a number of bad actors. The verbal nitpicking reached its silliest level in comparisons clashes over identity politics, as in this tweet from Raud:

2/11 Consider a prize for anti-racist activities divided between two white anti-racists and one activist of colour? Or a prize for feminist writing given to two men and one woman, all good feminists? I'm sure it would raise some eyebrows.

— Rein Raud (@reinraud) October 8, 2022

In fact, the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for “public service” journalism, for #MeToo reporting, went to one man and two women (the New Yorker’s Ronan Farrow and the New York Times’ Jodi Kantor and Megan Twoohey), and even in that highly gender-aware moment, I don’t recall any eyebrows being raised. One may add, too, that lumping together Russia and Belarus can also be seen as questionable: While Belarusian dictator Aleksandr Lukashenko has supported Putin’s war and allowed Belarusian territory to be used for Russian operations, he has also refused to send Belarusian troops to assist Russia, reportedly because of resistance among officers. In a cutting response to Podolyak on Twitter, Belarusian-born journalist Hannah Liubakova suggested that human rights activists such as Bialiatski deserved some of the credit for this resistance—and for the more active support from Belarusian volunteers fighting in Ukraine.

There is, in fact, a very different way to see the joint Nobel Peace Prize, expressed by Volodymyr Yavorsky, a Ukrainian lawyer and expert with the Ukrainian Center for the Civil Liberties. In an interview with the Radio Liberty/Radio Free Europe-sponsored Russian-language television channel Current Time, Yavorsky said that he did not see the award as suggesting that “we are one people . . . and that the problem is that we need to be persuaded to live in peace”:

The problem is that there are two authoritarian countries that are at war with a democratic country. . . . Today, this award emphasizes the fact that those people who are destroyed and persecuted in their countries—namely Belarusian and Russian human rights activists, who have been essentially forced to disband and some of whom are in prison—are basically fighting for freedom. And freedom is the antidote to this war and the antidote to the Russian regime.

Russian expatriate dissident Viktor Shenderovich also argued in an interview on the YouTube channel Zhivoi Gvozd’ (“The Live Nail”) that the joint Nobel Peace Prize was “above all, an obvious challenge to Vladimir Putin.” There is, he argued, a vitally important message in the fact that the people who are being honored in Russia (and in Belarus) are ones who are banned, disgraced, and branded foreign agents at home by their countries’ regimes. The underlying question here, of course, is to what extent Russians should be conflated with the Putin regime and held responsible for its crime. (Let’s for the moment leave aside Belarus, where things are more complicated.) This question has arisen on other occasions—notably, in the often-acrimonious debate about whether Russians fleeing conscription should be granted asylum in other countries. https://twitter.com/olgatokariuk/status/1575055717911830529 https://twitter.com/IlvesToomas/status/1575090148923932672 I think this attitude is wrong on both moral and practical grounds. On moral grounds, because the level of actual support for the war in Russia has been very difficult to gauge for many reasons, above all intimidation by the regime; in that sense, the blanket judgment that people fleeing mobilization were supportive of the Putin regime and complicit in its crimes against Ukrainians until they found themselves in personal danger is unwarranted and unjust. (What’s more, even the less than reliable Russian polls show that by June, a substantial minority of young Russians—a quarter of those 25 to 34 and 37 percent of those under 25—opposed the ”special operation” in Ukraine.) On practical grounds, because the exodus of potential draftees does undermine Putin’s war: It means less manpower and more image problems. But at least in that case, it was a question of asylum and benefits for people who had not stood up against the war or against the Putin regime. In the Nobel Peace Prize debate, the position taken by Podolyak and by a number of other journalists, activists, and social media users is hostile to Russian dissidents—people who, as a group, represent an extremely active opposition to Putin’s war in Ukraine. In short, this is a sad and counterproductive case of friendly fire. (In a similar vein, last month some people on pro-Ukraine Twitter railed against an Amnesty International campaign that supported a jailed Russian anti-war protester, using a graphic that showed an anti-war Russian hugging a Ukrainian.) Since it seems that no controversy is complete without a Nazi analogy, there are, inevitably, those who have sarcastically invoked the spectacle of a Nobel Peace Prize for Germany, Austria, and Poland in 1939. But, once again, the prize does not go to countries. The Nobel Peace Prize was on hold from 1939 to 1945, and Norway was occupied by German forces. Yet suppose a Nobel Prize Committee in exile had given the Peace Prize in the fall of 1944 to Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the theologian and dissident then imprisoned in a German concentration camp for his opposition to the Nazi regime and specifically to Hitler’s persecution of Jews (and who was executed in April 1945 as the regime was crumbling). Surely, to criticize such a move on the grounds that Bonhoeffer was a “representative of Germany” would have been profoundly wrong.