Peter Bogdanovich—one of the seminal and, at least at first, among the most successful of the New Hollywood filmmakers of the late 1960s and early ’70s—has died at the age of 82. Between 1971 and 1973, he produced and directed The Last Picture Show, What’s Up, Doc?, and Paper Moon (cowriting the former two), back-to-back-to-back critical and commercial triumphs. Following the path trodden by his French heroes like Francois Truffaut, Eric Rohmer, and other French New Wave directors who began their careers as film critics for Cahiers du Cinema, Bogdanovich made his bones as a film critic for Esquire before moving to Los Angeles with Polly Platt, his wife and eventual producing partner.

There, he fell in with Roger Corman and his independent film company. After spending some time doing grunt work for various ultra-low-budget productions, Bogdanovich began his directing career under Corman’s tutelage—the same route taken by Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and so many other of his contemporaries. He directed his first movie, Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women, under a pseudonym, before he was able to make films that were more personal to him. The fact that The Last Picture Show, a stark film that is able to find melancholy in what should be the joyousness of youth, was only his third film is a testament to the value of Bogdanovich’s obsessive study of such Old Hollywood greats as Howard Hawks and John Ford. The fact that The Last Picture Show is a Western, of a certain kind anyway, based on a novel by Larry McMurtry is not insignificant.

But after his short string of successes, Bogdanovich’s career began to founder. From 1975 to 1981, he struggled to reach those early peaks. Films like Nickelodeon and At Long Last Love were pummeled by critics and the still-young director was unable to retain a steady grip on his career. Some of the films during this period, like Saint Jack and They All Laughed, have subsequently been embraced by cinephiles and other filmmakers, but at the time things looked grim. Furthermore, Bogdanovich’s personal life, more so than most other directors, was the stuff of news. Having broken up with his frequent leading lady Cybill Shepherd, for whom he’d left Platt in 1971, Bogdanovich began a relationship with Playboy Playmate Dorothy Stratten. Stratten was one of the stars of They All Laughed, and of this film the director told IndieWire, “It might not be my best film I made, but it’s my favorite for personal reasons, obviously.” Regardless of the film’s reception, he went on to say that making it “was definitely the high point in my life.”

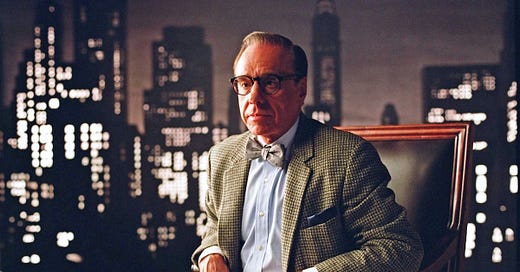

Peter Bogdanovich on the set of 'The Last Picture Show'

Tragically, before the film was released, Dorothy Stratten was brutally murdered by her ex-husband Paul Snider. This news was broken to Bogdanovich, over the phone, by Hugh Hefner. In The Killing of the Unicorn, his 1984 book about his relationship with Stratten, Hefner, and her murder, Bogdanovich writes of that phone call:

Dorothy dead? Why not say the whole world had blown up and all of us were dead? Everything that had ever happened to me in my life, everything in which I had ever believed, had been proved in one blinding explosion to be conclusively wrong. If Dorothy was dead, life was a terrible joke.

By the time his book was published, Bob Fosse had already released Star 80, his intensely disturbing film about the life and murder of Stratten. This is a picture Bogdanovich reviled, and intended, among other goals, to refute with his book.

Bogdanovich wrote many books over the course of his life, all having to do with film in one form or another. Among his best known are John Ford (1967, expanded and reprinted in 1978), This is Orson Welles (1992), a collection of transcripts of interviews with the legendary director (a personal favorite of mine), Who the Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors (1997), and his last book, a companion to Who the Devil Made It called Who the Hell’s In It: Conversations with Hollywood’s Legendary Actors (2004). Furthermore, in 1985 his directing career got back on track with Mask, a very fine movie starring Cher and Eric Stoltz, about the sad-but-inspiring life of Rocky Dennis. That’s the closest Bogdanovich would come to matching his past glory, but it’s not the last good picture he made. After Mask, Bogdanovich’s films as a director were sporadic, and, after Texasville (1990), a sequel to The Last Picture Show, usually fairly low budget. But he still had at least two terrific pictures left in him: Noises Off (1992), a very funny adaptation of Michael Frayn’s classic stage farce, and The Cat’s Meow (2001), a fictionalized account of the mysterious death of silent film producer Thomas Ince.

One of Bogdanovich's last contributions to film, and quite possibly his most valuable, was his decades-long effort to finish post-production on and secure distribution for Orson Welles's last picture, The Other Side of the Wind. Welles, with whom Bogdanovich had a long but turbulent friendship that ended before Welles's death, had finished shooting the movie in 1976, but struggled to complete post-production. He died in 1985, with the editing nowhere near done. Bogdanovich's on-again off-again struggle to finish his friend and mentor's last movie would every so often make the news, bringing hope that one day the public might actually get to see a "new" Orson Welles picture. Finally, in 2018, The Other Side of the Wind (in which Bogdanovich co-stars as a character with the very Wellesian name of Brooks Otterlake) premiered on Netflix. And the result of all this hard work was a film that could not feel more like Welles if the great man had lived to oversee the completion himself, a thunderous and wild meditation on morality, mortality, and cinema, a crazed epic that, without Peter Bogdanovich, would be stuck somewhere in a pile of film cannisters, gathering dust.

Onscreen, Bogdanovich found his most famous and lasting role late in life: Dr. Elliot Kupferberg, he of the comically oversized water bottle and therapist to Jennifer Melfi on The Sopranos. It was a recurring guest part, and quite memorable. But it is not the role I think of when I think of Bogdanovich.

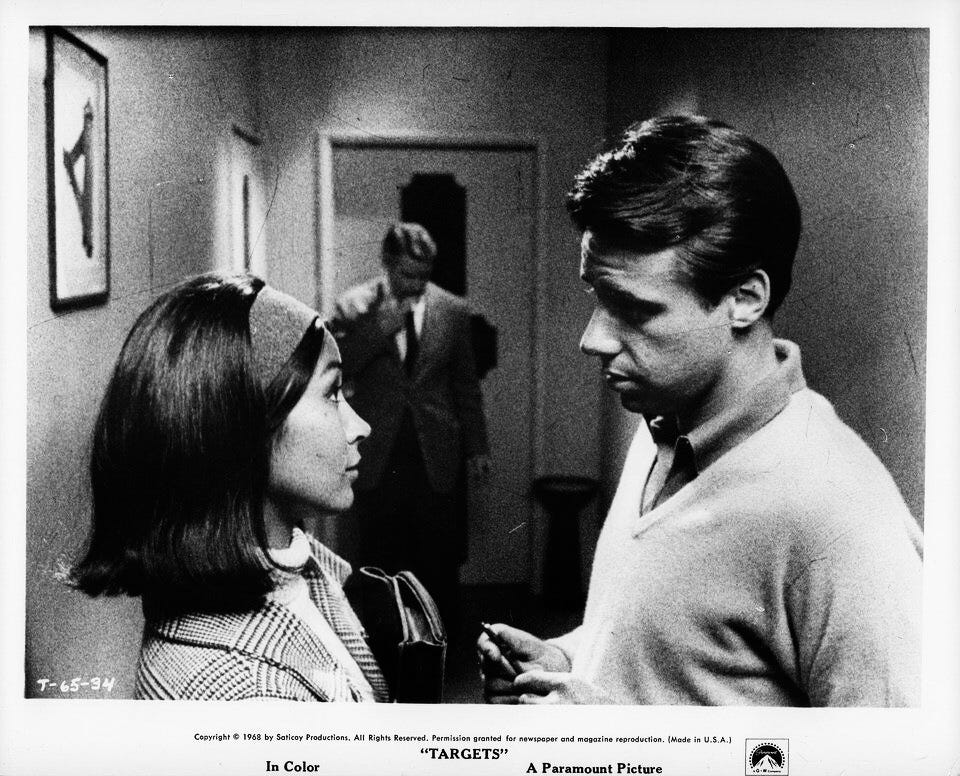

The first acting job for which Bogdanovich actually received a credit was in his second directorial effort, 1968’s Targets. Made for Corman, this was the first film Bogdanovich made that allowed him to inject any kind of personal artistic statement, or flair, or individual creativity of any kind. Corman’s assignment was straightforward as it was seemingly impossible: Because Boris Karloff’s contract with the producer stipulated that the actor still owed Corman two days of work, Bogdanovich had to make a movie featuring Karloff, get those two days of acting out of him, which would be filled out with twenty minutes from The Terror, a rather bad 1963 horror film directed by Corman and starring Karloff and Jack Nicholson. As long as Bogdanovich could meet those requirements, the movie could be whatever Bogdanovich wanted it to be. And what Targets is, in my view, is the best film Bogdanovich ever made, one of the best films of the ’60s, and one of the best of all the New Hollywood pictures.

Bogdanovich didn’t quite meet Corman’s demands; for instance, the amount of footage from The Terror used in Targetsisn’t quite twenty minutes, but closer to three. The ingenious premise that Bogdanovich and Polly Platt (assisted by Samuel Fuller, who did an uncredited rewrite on the script, according to Bogdanovich on the DVD commentary) came up with was this: Karloff plays Byron Orlok, in essence a version of himself, an aging horror movie actor who is on a press tour to promote his newest, and last, film, which was directed by Sammy Michaels (Bogdanovich). This being the late 1960s, America is in turmoil, and a new kind of violence, and a new kind of terror, is finding its way into the country. Two years before Targets was made, Charles Whitman climbed to the top of the Main Building tower of the University of Texas and killed fifteen people. In Targets, a fictional version of this plays out in parallel to the story of Orlok’s bittersweet farewell tour. Like Whitman, Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly) first murders his family. Then he climbs up a water tower and begins shooting at cars on the highway, killing many people, before moving his base to the drive-in theater where, that night, Orlok’s film is set to premiere. It is Thompson’s plan to station himself on a platform behind the screen, and fire through a hole in the screen at the audience watching from their cars.

Part of what makes Orlok’s half of the story so melancholy, apart from the obvious fact that this man is reaching the end of his life (Karloff himself died one year later), is the understanding Orlok has that his brand of fun, Gothic horror is now passé. The new horrors of the world are too overwhelming for his films to have any impact on an audience. At one point, Orlok says to Michaels, “Oh, Sammy, what's the use? Mr. Boogey Man, King of Blood they used to call me. Marx Brothers make you laugh, Garbo makes you weep, Orlok makes you scream.” In short, it’s just a genre, it just presses buttons in the audience. It’s impossible to watch an Orlok movie and find any meaning, any worth, any significance, when the real world outside seems itself to be screaming.

And indeed, when Thompson is not shooting at innocent strangers who are probably just driving home from work from atop the water tower, Bogdanovich shows him sitting peacefully, one rifle across his lap, four more in a net row next to him, while he unwraps a sandwich he brought with him in a paper bag. Also next to him is a bottle of soda. He brought his lunch. He’s taking a break. There are few shots in American film as banally terrifying as that one.

One of the most best scenes in Targets, and one that acts as an interesting counterpoint to the rest of the film, is the one where Orlok tells the story of “The Appointment in Samarra,” recorded in the Babylonian Talmud and famously retold by W. Somerset Maugham, in which a merchant tries, and fails, to avoid Death. Though it predates the literary form that takes the name, the story is nevertheless classically Gothic, and Orlok/Karloff’s narration of it has a cold and grim timelessness. It also basically sums up the horror genre, to which Targets arguably belongs, and, as it sums up Bobby Thompson (and Charles Whitman), it acts as a defense against Orlok’s own estimation of the kind of films he’s given his life to. The scene even contextualizes Karloff’s own place in the history of cinema. There is so much going on in this short, unbroken take that it’s almost breathtaking.

This is possibly Karloff’s finest performance. Bogdanovich, who was no great fan of his own performance, is quite good in Targets, too. The film, I think, is a masterpiece; it’s also one of the most incongruous in his long and tumultuous career (its closest competition for this prize is Runnin’ Down a Dream, his four-hour documentary about Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers). Which merely tells me that Bogdanovich’s career was varied, that his interests and obsessions were expansive and restless, and his artistry was subtle, at times almost subliminal—but when matched to material that deserved it, entirely wonderful and bracing.